Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

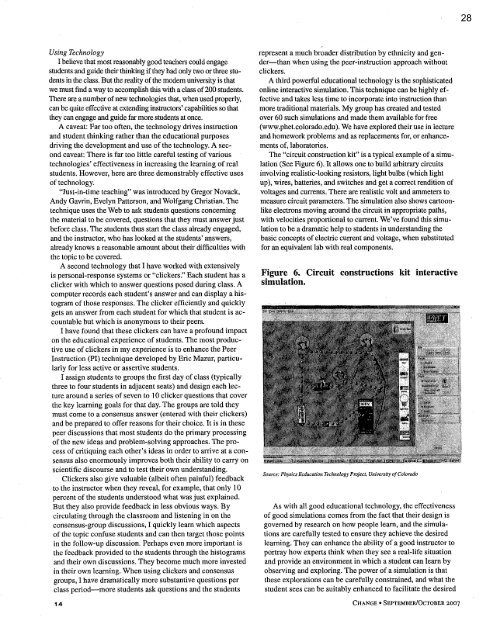

28Using TechnologyI believe that most reasonably good teachers could engagestudents and guide their thinking if they had only two or three studentsin the class. But the reality of the modem university is thatwe must find a way to accomplish this with a class of 200 students.There are a number of new technologies that, when used properly,can be quite effective at extending instructors' capabilities so thatthey can engage and guide far more students at once.A caveat: Far too often, the technology drives instructionand student thinking rather than the educational purposesdriving the development and use of the technology. A secondcaveat: There is far too little careful testing of varioustechnologies' effectiveness in increasing the learning of realstudents. However, here are three demonstrably effective usesof technology."Just-in-time teaching" was introduced by Gregor Novack,Andy Gavrin, Evelyn Patterson, and Wolfgang Christian. Thetechnique uses the Web to ask students questions concerningthe material to be covered, questions that they must answer justbefore class. The students thus start the class already engaged,and the instructor, who has looked at the students' ~swers,already knows a reasonable amount about their difficulties withthe topic to be covered.A second technology that I have worked with extensivelyis personal-response systems or "clickers." Each student has aclicker with which to answer questions posed during class. Acomputer records each student's answer and can display a histogramof those responses. The clicker efficiently and quicklygets an answer from each student for which that student is accountablebut which is anonymous to their peers.I have found that these clickers can have a profound impacton the educational experience of students. The most productiveuse of clickers in my experience is to enhance the PeerInstruction (PI) technique developed by Eric Mazur, particularlyfor less active or assertive students.I assign students to groups the first day of class (typicallythree to four students in adjacent seats) and design each lecturearound a series of seven to 1 0 clicker questions that coverthe key learning goals for that day. The groups are told theymust come to a consensus answer (entered with their clickers)and be prepared to offer reasons for their choice. It is in thesepeer discussions that most students do the primary processingof the new ideas and problem-solving approaches. The processof critiquing each other's ideas in order to arrive at a consensusalso enormously improves both their ability to carry onscientific discourse and to test their own understanding.Clickers also give valuable (albeit often painful) feedbackto the instructor when they reveal, for example, that only 10percent of the students understood what was just explained.But they also provide feedback in less obvious ways. Bycirculating through the classroom and listening in on theconsensus-group discussions, I quickly learn which aspectsof the topic confuse students and can then target those pointsin the follow-up discussion. Perhaps even more important isthe feedback provided to the students through the histogramsand their own discussions. They become much more investedin their own learning. When using clickers and consensusgroups, I have dramatically more substantive questions perclass period-more students ask questions and the students14represent a much broader distribution by ethnicity and gender-thanwhen using the peer-instruction approach withoutclickers.A third powerful educational technology is the sophisticatedonline interactive simulation. This technique can be highly effectiveand takes less time to incorporate into instruction thanmore traditional materials. My group has created and testedover 60 such simulations and made them available for free(www.phet.colorado.edu). We have explored their use in lectureand homework problems and as replacements for, or enhancementsof, laboratories.The "circuit construction kit" is a typical example of a simulation(See Figure 6). It allows one to build arbitrary circuitsinvolving realistic-looking resistors, light bulbs (which lightup), wires, batteries, and switches and get a correct rendition ofvoltages and currents. There are realistic volt and ammeters tomeasure circuit parameters. The simulation also shows cartoonlikeelectrons moving around the circuit in appropriate paths,with velocities proportional to current. We've found this simulationto be a dramatic help to students in understanding thebasic concepts of electric current and voltage, when substitutedfor an equivalent lab with real components.Figure 6. Circuit constructions kit interactivesimulation.Source: Physics Ecducation Technology Project, University of ColoradoAs with all good educational technology, the effectivenessof good simulations comes from the fact that their design isgoverned by research on how people learn, and the simulationsare carefully tested to ensure they achieve the desiredlearning. They can enhance the ability of a good instructor toportray how experts think when they see a real-life situationand provide an environment in which a student can learn byobserving and exploring. The power of a simulation is thatthese explorations can be carefully constrained, and what thestudent sees can be suitably enhanced to facilitate the desiredCHANGE • SEPTEMBERIOCTOBER 2007