- Page 2 and 3:

Hypoglycaemia in Clinical DiabetesS

- Page 4 and 5:

Hypoglycaemia in Clinical DiabetesS

- Page 6:

ToEmily, Ben and Marc

- Page 9 and 10:

viiiCONTENTS13 Long-term Effects of

- Page 12 and 13:

ContributorsProfessor Stephanie A.

- Page 14 and 15:

1 Normal Glucose Metabolismand Resp

- Page 16 and 17:

NORMAL GLUCOSE HOMEOSTASIS 3Box 1.2

- Page 18 and 19:

Fed state (Figure 1.1b)EFFECTS OF G

- Page 20 and 21:

COUNTERREGULATION DURING HYPOGLYCAE

- Page 22 and 23:

COUNTERREGULATION DURING HYPOGLYCAE

- Page 24 and 25:

HORMONAL CHANGES DURING HYPOGLYCAEM

- Page 26 and 27:

HORMONAL CHANGES DURING HYPOGLYCAEM

- Page 28 and 29:

PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES 15hormones.

- Page 30 and 31:

PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES 17Figure 1.

- Page 32 and 33:

PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES 19We do not

- Page 34 and 35:

REFERENCES 21NORMAL GLUCOSE HOMEOST

- Page 36 and 37:

REFERENCES 23Hamilton-Wessler M, Be

- Page 38 and 39:

2 Symptoms of Hypoglycaemiaand Effe

- Page 40 and 41:

SYMPTOMS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 27appeare

- Page 42 and 43:

SYMPTOMS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 29aware o

- Page 44 and 45:

SYMPTOMS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 31Table 2

- Page 46 and 47:

SYMPTOMS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 33frequen

- Page 48 and 49:

SYMPTOMS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 35Figure

- Page 50 and 51:

ACUTE HYPOGLYCAEMIA AND COGNITIVE F

- Page 52 and 53:

ACUTE HYPOGLYCAEMIA AND COGNITIVE F

- Page 54 and 55: ACUTE HYPOGLYCAEMIA AND COGNITIVE F

- Page 56 and 57: ACUTE HYPOGLYCAEMIA AND EMOTIONS 43

- Page 58 and 59: REFERENCES 45Bremer JP, Baron M, Pe

- Page 60 and 61: REFERENCES 47McAulay V, Deary IJ, F

- Page 62 and 63: 3 Frequency, Causes and RiskFactors

- Page 64 and 65: FREQUENCY OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 51Box 3.

- Page 66 and 67: Table 3.1 Frequency of mild hypogly

- Page 68 and 69: FREQUENCY OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 55some i

- Page 70 and 71: FREQUENCY OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 57Jansse

- Page 72 and 73: Table 3.2 Frequency of severe hypog

- Page 74 and 75: CAUSES OF HYPOGLYCAEMIACAUSES OF HY

- Page 76 and 77: RISK FACTORS FOR SEVERE HYPOGLYCAEM

- Page 78 and 79: RISK FACTORS FOR SEVERE HYPOGLYCAEM

- Page 80 and 81: RISK FACTORS FOR SEVERE HYPOGLYCAEM

- Page 82 and 83: RISK FACTORS FOR SEVERE HYPOGLYCAEM

- Page 84 and 85: RISK FACTORS FOR SEVERE HYPOGLYCAEM

- Page 86 and 87: RISK FACTORS FOR SEVERE HYPOGLYCAEM

- Page 88 and 89: CONCLUSIONS 75Other Risk FactorsThe

- Page 90 and 91: REFERENCES 77Bott S, Bott U, Berger

- Page 92 and 93: REFERENCES 79Leckie AM, Graham MK,

- Page 94: REFERENCES 81Vervoort G, Goldschmid

- Page 97 and 98: Table 4.1 Frequency of nocturnal hy

- Page 99 and 100: 86 NOCTURNAL HYPOGLYCAEMIACAUSES OF

- Page 101 and 102: 88 NOCTURNAL HYPOGLYCAEMIAPlasma Ep

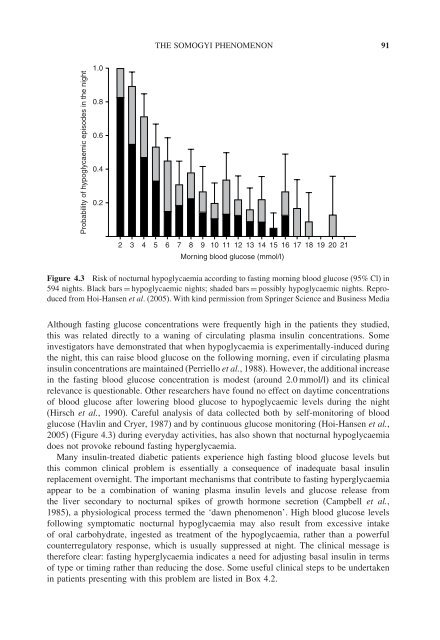

- Page 103: 90 NOCTURNAL HYPOGLYCAEMIACAN NOCTU

- Page 107 and 108: 94 NOCTURNAL HYPOGLYCAEMIAconflicti

- Page 109 and 110: 96 NOCTURNAL HYPOGLYCAEMIA• Noctu

- Page 111 and 112: 98 NOCTURNAL HYPOGLYCAEMIAHolleman

- Page 114 and 115: 5 Moderators, Monitoring andManagem

- Page 116 and 117: LIFESTYLE MODERATORS 103• absolut

- Page 118 and 119: LIFESTYLE MODERATORS 10520 22 24 2

- Page 120 and 121: LIFESTYLE MODERATORS 107Growthhormo

- Page 122 and 123: LIFESTYLE MODERATORS 109mean change

- Page 124 and 125: MONITORING 111flow) while simultane

- Page 126 and 127: MONITORING 113• It is unclear whe

- Page 128 and 129: MANAGEMENT OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA 115MANA

- Page 130 and 131: REFERENCES 117CONCLUSIONS• Hypogl

- Page 132 and 133: REFERENCES 119MacDonald MJ (1987).

- Page 134 and 135: 6 Counterregulatory Deficienciesin

- Page 136 and 137: NORMAL GLUCOSE COUNTERREGULATION 12

- Page 138 and 139: NORMAL GLUCOSE COUNTERREGULATION 12

- Page 140 and 141: DEFECTIVE HORMONAL GLUCOSE COUNTERR

- Page 142 and 143: DEFECTIVE HORMONAL GLUCOSE COUNTERR

- Page 144 and 145: MECHANISMS OF COUNTERREGULATORY FAI

- Page 146 and 147: AGE, OBESITY AND GLUCOSE COUNTERREG

- Page 148 and 149: TREATMENT OF COUNTERREGULATORY FAIL

- Page 150 and 151: REFERENCES 137Bingham EM, Dunn JT,

- Page 152 and 153: REFERENCES 139McCall AL, Fixman LB,

- Page 154 and 155:

7 Impaired Awareness ofHypoglycaemi

- Page 156 and 157:

NORMAL RESPONSES TO HYPOGLYCAEMIA 1

- Page 158 and 159:

IMPAIRED AWARENESS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA

- Page 160 and 161:

PREVALENCE OF IMPAIRED AWARENESS OF

- Page 162 and 163:

PATHOGENESIS OF IMPAIRED AWARENESS

- Page 164 and 165:

PATHOGENESIS OF IMPAIRED AWARENESS

- Page 166 and 167:

PATHOGENESIS OF IMPAIRED AWARENESS

- Page 168 and 169:

PATHOGENESIS OF IMPAIRED AWARENESS

- Page 170 and 171:

PATHOGENESIS OF IMPAIRED AWARENESS

- Page 172 and 173:

Table 7.3 Studies of antecedent hyp

- Page 174 and 175:

IMPAIRED AWARENESS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA

- Page 176 and 177:

TREATMENT STRATEGIES 163or unexplai

- Page 178 and 179:

CONCLUSIONS 165Box 7.5 Treatment st

- Page 180 and 181:

REFERENCES 167Boyle PJ (1997). Alte

- Page 182 and 183:

REFERENCES 169Kerr D, Sherwin RS, P

- Page 184 and 185:

8 Risks of Strict GlycaemicControlS

- Page 186 and 187:

CONTRIBUTORS TO INCREASED RISK OF S

- Page 188 and 189:

CONTRIBUTORS TO INCREASED RISK OF S

- Page 190 and 191:

CEREBRAL ADAPTATION 177severe, are

- Page 192 and 193:

CEREBRAL ADAPTATION 179hypoglycaemi

- Page 194 and 195:

THERAPEUTIC MANIPULATION 181Figure

- Page 196 and 197:

PATIENTS UNSUITABLE FOR STRICT CONT

- Page 198 and 199:

REFERENCES 185It is the patient who

- Page 200 and 201:

REFERENCES 187Egger M, Davey Smith

- Page 202:

REFERENCES 189Simonson DC, Tamborla

- Page 205 and 206:

192 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 207 and 208:

Table 9.2 Summary of studies examin

- Page 209 and 210:

196 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 211 and 212:

198 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 213 and 214:

200 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 215 and 216:

202 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 217 and 218:

204 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 219 and 220:

206 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 221 and 222:

208 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 223 and 224:

210 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 225 and 226:

212 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 227 and 228:

214 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN CHILDREN WITH

- Page 230 and 231:

10 Hypoglycaemia in PregnancyAnn E.

- Page 232 and 233:

FREQUENCY OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN DIABE

- Page 234 and 235:

FREQUENCY OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN DIABE

- Page 236 and 237:

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT BEFORE AND DURI

- Page 238 and 239:

Figure 10.2 Example of home blood g

- Page 240 and 241:

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT BEFORE AND DURI

- Page 242 and 243:

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT BEFORE AND DURI

- Page 244 and 245:

MATERNAL COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES

- Page 246 and 247:

COMPLICATIONS IN THE INFANT OF THE

- Page 248 and 249:

REFERENCES 235Akazawa M, Akazawa S,

- Page 250:

REFERENCES 237Ray JG, O’Brien TE,

- Page 253 and 254:

240 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 255 and 256:

242 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 257 and 258:

244 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 259 and 260:

246 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 261 and 262:

Table 11.2a Prevalence of severe hy

- Page 263 and 264:

250 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 265 and 266:

252 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 267 and 268:

254 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 269 and 270:

256 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 271 and 272:

258 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 273 and 274:

260 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 275 and 276:

262 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 277 and 278:

264 HYPOGLYCAEMIA IN TYPE 2 DIABETE

- Page 279 and 280:

266 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 281 and 282:

268 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 283 and 284:

270 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 285 and 286:

272 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 287 and 288:

274 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 289 and 290:

276 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 291 and 292:

278 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 293 and 294:

280 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 295 and 296:

282 MORTALITY, CARDIOVASCULAR MORBI

- Page 298 and 299:

13 Long-term Effects ofHypoglycaemi

- Page 300 and 301:

COGNITIVE FUNCTION AND HYPOGLYCAEMI

- Page 302 and 303:

FUNCTIONAL EFFECTS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA

- Page 304 and 305:

FUNCTIONAL EFFECTS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA

- Page 306 and 307:

FUNCTIONAL EFFECTS OF HYPOGLYCAEMIA

- Page 308 and 309:

STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL CHANGES I

- Page 310 and 311:

STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL CHANGES I

- Page 312 and 313:

STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL CHANGES I

- Page 314 and 315:

STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL CHANGES I

- Page 316 and 317:

REFERENCES 303disease (Fisher and F

- Page 318 and 319:

REFERENCES 305Fisher M, Frier BM (1

- Page 320:

REFERENCES 307Seidl R, Birnbacher R

- Page 323 and 324:

310 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAPSYCHO

- Page 325 and 326:

312 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIABox 14

- Page 327 and 328:

314 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAprophy

- Page 329 and 330:

316 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAMost t

- Page 331 and 332:

318 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAfor pu

- Page 333 and 334:

320 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAVocati

- Page 335 and 336:

322 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAif the

- Page 337 and 338:

324 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAestabl

- Page 339 and 340:

326 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAwith g

- Page 341 and 342:

328 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAalcoho

- Page 343 and 344:

330 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIAChante

- Page 345 and 346:

332 LIVING WITH HYPOGLYCAEMIASonger

- Page 347 and 348:

334 INDEXanterior pituitary gland,

- Page 349 and 350:

336 INDEXcomplications due to diabe

- Page 351 and 352:

338 INDEXemployment aspects, 323-32

- Page 353 and 354:

340 INDEXhypopituitarism, 74, 102,

- Page 355 and 356:

342 INDEXmood changes due to hypogl

- Page 357 and 358:

344 INDEXpsychological factors, and

- Page 359:

346 INDEXtrain drivers, 323, 324tra