APRILFeedback

Feedback April 2003 (Vol. 44, No. 2) - Broadcast Education ...

Feedback April 2003 (Vol. 44, No. 2) - Broadcast Education ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

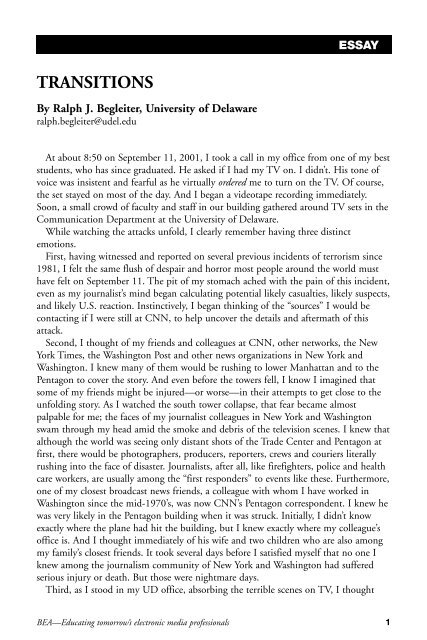

ESSAYTRANSITIONSBy Ralph J. Begleiter, University of Delawareralph.begleiter@udel.eduAt about 8:50 on September 11, 2001, I took a call in my office from one of my beststudents, who has since graduated. He asked if I had my TV on. I didn’t. His tone ofvoice was insistent and fearful as he virtually ordered me to turn on the TV. Of course,the set stayed on most of the day. And I began a videotape recording immediately.Soon, a small crowd of faculty and staff in our building gathered around TV sets in theCommunication Department at the University of Delaware.While watching the attacks unfold, I clearly remember having three distinctemotions.First, having witnessed and reported on several previous incidents of terrorism since1981, I felt the same flush of despair and horror most people around the world musthave felt on September 11. The pit of my stomach ached with the pain of this incident,even as my journalist’s mind began calculating potential likely casualties, likely suspects,and likely U.S. reaction. Instinctively, I began thinking of the “sources” I would becontacting if I were still at CNN, to help uncover the details and aftermath of thisattack.Second, I thought of my friends and colleagues at CNN, other networks, the NewYork Times, the Washington Post and other news organizations in New York andWashington. I knew many of them would be rushing to lower Manhattan and to thePentagon to cover the story. And even before the towers fell, I know I imagined thatsome of my friends might be injured—or worse—in their attempts to get close to theunfolding story. As I watched the south tower collapse, that fear became almostpalpable for me; the faces of my journalist colleagues in New York and Washingtonswam through my head amid the smoke and debris of the television scenes. I knew thatalthough the world was seeing only distant shots of the Trade Center and Pentagon atfirst, there would be photographers, producers, reporters, crews and couriers literallyrushing into the face of disaster. Journalists, after all, like firefighters, police and healthcare workers, are usually among the “first responders” to events like these. Furthermore,one of my closest broadcast news friends, a colleague with whom I have worked inWashington since the mid-1970’s, was now CNN’s Pentagon correspondent. I knew hewas very likely in the Pentagon building when it was struck. Initially, I didn’t knowexactly where the plane had hit the building, but I knew exactly where my colleague’soffice is. And I thought immediately of his wife and two children who are also amongmy family’s closest friends. It took several days before I satisfied myself that no one Iknew among the journalism community of New York and Washington had sufferedserious injury or death. But those were nightmare days.Third, as I stood in my UD office, absorbing the terrible scenes on TV, I thoughtBEA—Educating tomorrow’s electronic media professionals 1