Eric Vittoz - IEEE

Eric Vittoz - IEEE

Eric Vittoz - IEEE

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TECHNICAL LITERATURE<br />

It’s about Time: A Brief Chronology of Chronometry<br />

Thomas H. Lee, Stanford University, tomlee@ee.stanford.edu<br />

Prologue<br />

The lobby clock’s label boasted, in HP’s characteristically<br />

understated way, that a cesium standard controlled<br />

the displayed time. While waiting for his host<br />

to greet him, Max Forrer reflexively checked his wristwatch,<br />

and noted a three-second disagreement.<br />

Although most people in 1968 would have dismissed<br />

the difference as trivial (if, indeed, they had noticed<br />

one at all), the discrepancy bothered the new director<br />

of the Centre Electronique Horloger (CEH). Since<br />

CEH’s founding in 1962, engineers had toiled in secret<br />

at the Centre’s labs in Neuchâtel, Switzerland to<br />

develop the world’s first quartz-controlled wristwatch.<br />

They had succeeded brilliantly: In December of 1967,<br />

ten “Beta 2” prototypes had swept the top ten spots<br />

in the annual Concours held at the Observatoire de<br />

Neuchâtel, smashing all previous records by exhibiting<br />

drifts of only a few hundred milliseconds per day.<br />

Given the magnitude and consistency of that triumph,<br />

Forrer could not accept that his wristwatch was off by<br />

three seconds. Of logical necessity, then, the lobby<br />

clock had to be wrong, cesium notwithstanding. Once<br />

his host appeared, Forrer shared his reasoning, and a<br />

subsequent investigation revealed that the lobby<br />

clock was indeed off by about two seconds [1]. Word<br />

spread quickly among HP engineers that a wristwatch<br />

had caught an error in their atomic-controlled clock.<br />

The times – and certainly timepieces – they were “achangin.”<br />

The Age of Continuous Time<br />

Rejoice at simple things; and be but vexed by sin and<br />

evil slightly.<br />

Know the tides through which we move.<br />

– Archilochos, c. 650BCE<br />

The path to Forrer’s moment of rejoicing was anything<br />

but linear and predictable. Simple things – natural,<br />

continuous processes – such as the regular<br />

motions of the sun, moon and stars, had marked the<br />

tides through which we move for most of human<br />

existence. Sundials had been used since at least 3500<br />

BCE, when obelisks appeared for this purpose in<br />

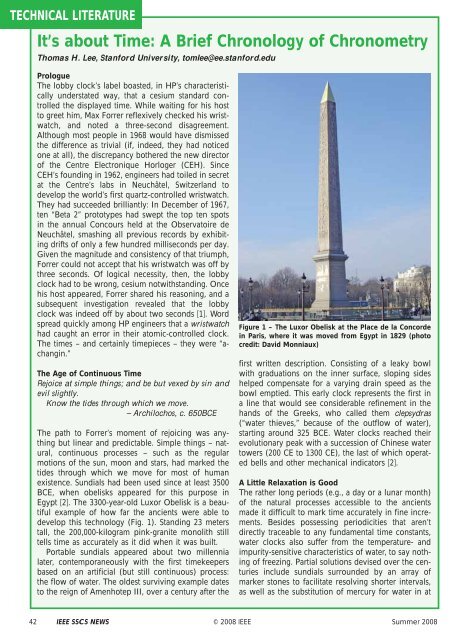

Egypt [2]. The 3300-year-old Luxor Obelisk is a beautiful<br />

example of how far the ancients were able to<br />

develop this technology (Fig. 1). Standing 23 meters<br />

tall, the 200,000-kilogram pink-granite monolith still<br />

tells time as accurately as it did when it was built.<br />

Portable sundials appeared about two millennia<br />

later, contemporaneously with the first timekeepers<br />

based on an artificial (but still continuous) process:<br />

the flow of water. The oldest surviving example dates<br />

to the reign of Amenhotep III, over a century after the<br />

Figure 1 – The Luxor Obelisk at the Place de la Concorde<br />

in Paris, where it was moved from Egypt in 1829 (photo<br />

credit: David Monniaux)<br />

first written description. Consisting of a leaky bowl<br />

with graduations on the inner surface, sloping sides<br />

helped compensate for a varying drain speed as the<br />

bowl emptied. This early clock represents the first in<br />

a line that would see considerable refinement in the<br />

hands of the Greeks, who called them clepsydras<br />

(“water thieves,” because of the outflow of water),<br />

starting around 325 BCE. Water clocks reached their<br />

evolutionary peak with a succession of Chinese water<br />

towers (200 CE to 1300 CE), the last of which operated<br />

bells and other mechanical indicators [2].<br />

A Little Relaxation is Good<br />

The rather long periods (e.g., a day or a lunar month)<br />

of the natural processes accessible to the ancients<br />

made it difficult to mark time accurately in fine increments.<br />

Besides possessing periodicities that aren’t<br />

directly traceable to any fundamental time constants,<br />

water clocks also suffer from the temperature- and<br />

impurity-sensitive characteristics of water, to say nothing<br />

of freezing. Partial solutions devised over the centuries<br />

include sundials surrounded by an array of<br />

marker stones to facilitate resolving shorter intervals,<br />

as well as the substitution of mercury for water in at<br />

42 <strong>IEEE</strong> SSCS NEWS © 2008 <strong>IEEE</strong> Summer 2008