Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

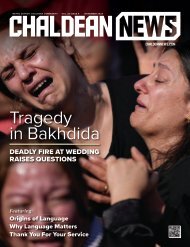

COVER STORY<br />

On the Run in America<br />

An Iraqi Christian’s struggle to stay<br />

one step ahead of ICE<br />

BY AMANDA UHLE<br />

Originally printed in The Delacorte<br />

Review August 15, <strong>2022</strong>.<br />

ILLUSTRATION BY LÉO HAMELIN<br />

In winter, the four-hour drive from<br />

Detroit to Youngstown is particularly<br />

bleak. One February 2018 day<br />

I couldn’t discern any contrast between<br />

the snow on the farm fields, the faded<br />

white of gambrel-roofed barns, and the<br />

dove-gray sky behind them. The landscape<br />

alternates between fast food and<br />

agriculture, the flat road stretching on<br />

and on. Drive the length of Ohio and<br />

you’ll pay more than $15 in tolls.<br />

For more than a year at that time,<br />

dozens of Detroit families made this drive<br />

often to see detained fathers, husbands,<br />

brothers, and uncles, all held by ICE at<br />

the Northeast Ohio Correctional Center.<br />

I joined them, and on one of my visits, I<br />

was scheduled to meet two men for backto-back<br />

interviews. Instead, prison staff<br />

decided we could all talk together.<br />

So Peter Abbo—a name I’m using<br />

for this story to protect his anonymity—<br />

pushed another man’s wheelchair into a<br />

tiny metal room, the two of them sharing<br />

a single phone on their side of the plexiglass.<br />

Peter was bald and pale, a red-orange<br />

beard on his chin but no mustache<br />

above it. The man in the wheelchair fit a<br />

more expected version of “Middle Eastern,”<br />

with olive skin and graying black<br />

hair. They looked nothing alike but had<br />

established a brotherly rhythm, telling<br />

each other’s stories, passing the plastic<br />

phone between them. Neither man’s<br />

family had visited yet. Peter’s wife had<br />

breast cancer, I learned, and the other<br />

man had a first-grade son.<br />

The man in the wheelchair dominated<br />

the phone but if Peter was annoyed,<br />

he didn’t betray it. When I indicated<br />

that Peter should speak he did<br />

so with equal urgency, but also with a<br />

self-effacing demeanor. Repeatedly he<br />

said, “I take responsibility” or “I did it.<br />

I own that,” in explaining his crimes<br />

and circumstances.<br />

Peter pressed a family photo and a<br />

Xerox of a handwritten letter against the<br />

plexiglass for me to read. The judge at<br />

his recent hearing had ignored the letter,<br />

and Peter wanted me to see the injustice<br />

of it, to understand his situation.<br />

These were two of more than 300<br />

Iraqi-born Detroit-area men arrested<br />

in a surprise ICE raid back on Sunday<br />

morning, June 11, 2017. They both have<br />

criminal records, for which they’ve<br />

served time. In 2010, the man in the<br />

wheelchair worked in a liquor store that<br />

sold fake Nike shoes. He was charged<br />

with a counterfeiting felony and went<br />

to prison. Seven years later, shoeless<br />

and in his underwear at six in the<br />

morning, he was handcuffed and taken<br />

out of his home and into one of the<br />

SWAT vehicles idling on his suburban<br />

street. More quietly, in the weeks before<br />

and after, others were arrested in Michigan<br />

and beyond. At the time there were<br />

just over 1,300 men in the U.S. who fell<br />

into a narrow category of immigration<br />

law—Iraqi-born people who had “final<br />

orders of deportation.” A few had been<br />

convicted of serious crimes. Many more<br />

were guilty of non-violent offenses or<br />

even simple lapses in paperwork. In the<br />

summer of 2017, the Trump administration<br />

planned to deport them all.<br />

This was a hard turn in policy. For<br />

decades, the U.S. did not deport Iraqis.<br />

The situation in that nation was deemed<br />

so dangerous that even the George W.<br />

Bush administration had understood it<br />

to be inhumane to deport Iraqis to Iraq.<br />

People who had been “Americanized”<br />

by spending time in the U.S. would be in<br />

extreme danger there, and their presence<br />

was considered a risk to Iraq’s precarious<br />

security situation. Citing logistical and<br />

humanitarian reasons, the Iraqi government<br />

refused to repatriate them anyway.<br />

Under current immigration law, felons<br />

generally cannot remain in the U.S.<br />

But when an Iraqi-born person was<br />

convicted of a felony, he or she would<br />

be sentenced according to the courts<br />

and then, instead of being deported,<br />

as other foreign-born felons might be,<br />

they were assigned supervision from<br />

ICE—usually monthly or annual checkins.<br />

Officially their status included the<br />

designation “under final orders of deportation,”<br />

even though the deportation<br />

aspect hadn’t happened in a generation.<br />

Sending someone back to Iraq<br />

was all but unimaginable.<br />

Until it wasn’t.<br />

ON THE RUN continued on page 22<br />

20 CHALDEAN NEWS <strong>SEPTEMBER</strong> <strong>2022</strong>