You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

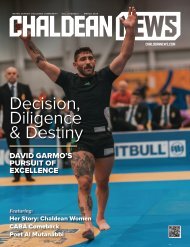

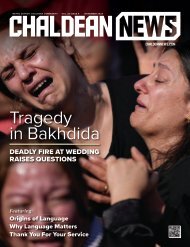

COVER STORY<br />

ON THE RUN continued from page 22<br />

night, at a liquor store on 6 Mile and<br />

Telegraph. That neighborhood was<br />

also a hub for drugs. “I used to look at<br />

the dope dealers and think, well, what<br />

a life. I mean that’s what you saw,” he<br />

said. “Starting in mid-’80s, mid-’90s,<br />

there was nothing but cocaine, hard<br />

drugs, fighting, robbing, killing.”<br />

On Mother’s Day 1990, when Peter<br />

had just turned twenty-one, he<br />

was hanging out with several high<br />

school friends near a party store. One<br />

of them, he says, spontaneously decided<br />

to rob someone coming out. The<br />

man was holding a bouquet of flowers,<br />

presumably for a mother in his<br />

life. As he opened the door of his car,<br />

a red Corvette, Peter’s friend pulled<br />

a gun on the man, took his keys, and<br />

got in the car, yelling at Peter to hop<br />

in. This had not been Peter’s idea. He<br />

says he felt almost as confused as the<br />

Corvette owner. But Peter opened the<br />

passenger door, grabbed the flowers<br />

from the front seat, handed them to<br />

the man who’d bought them, and got<br />

in the back seat.<br />

“Stupid, stupid,” Peter says, recalling<br />

the incident. “Me and another guy<br />

jumped in the car and took off.” They<br />

drove the Corvette for ten minutes<br />

around Chaldean Town. The police<br />

asked the victim who stole the car, and<br />

the owner reported that one of them<br />

was a redhead. “Everyone else with me<br />

was African-American. So the police<br />

knew exactly who it was,” Peter said.<br />

“I am the only red-haired guy in that<br />

neighborhood. When they came to<br />

me, they asked me whether I was the<br />

guy with a gun. I said I was. I couldn’t<br />

snitch. In that neighborhood, in that<br />

time, you can’t do that. They would<br />

have burned my house.”<br />

Peter says he never held the gun. He<br />

was holding the bouquet during most<br />

of the frenzied interaction. The victim<br />

agreed and told law enforcement so at<br />

a hearing—that Peter was an accessory<br />

and bystander, but not the gunman.<br />

“He said that I had nothing to do with<br />

it,” Peter said, that he had been “nice<br />

enough to give him his flowers back because<br />

it was Mother’s Day.”<br />

Peter was offered a plea bargain for<br />

a lower charge, unarmed robbery, but<br />

when he got the paperwork it was for<br />

the original charge, armed robbery. But<br />

Peter still agreed to protect his friends,<br />

and to protect himself from retribution.<br />

“I was young and stupid,” Peter said.<br />

He served one year and three months<br />

in a state prison. He’d understood that<br />

the plea meant his record would be<br />

clean, but he was wrong—those ten minutes<br />

in 1990 are indelibly marked on his<br />

record as “armed robbery.” His family<br />

paid $1,000 for the lawyer who urged<br />

him to take the plea deal. It’s unclear<br />

whether this lawyer considered the consequences<br />

of adding a felony to an immigrant’s<br />

record, or if he did understand<br />

but assumed that it was irrelevant, since<br />

Iraqis were never deported anyway.<br />

Peter spent his twenties back in<br />

the same Detroit neighborhood. His<br />

girlfriend got pregnant and then left,<br />

shortly after their son was born. Peter<br />

and his mother raised the boy together.<br />

There was never enough money.<br />

“It’s so stupid to even say it now,” he<br />

tells me, “but I wanted to be a drug<br />

dealer. They had money, friends. They<br />

were the only ones who didn’t have to<br />

worry. I should have wanted to be a<br />

doctor, but I didn’t know to want that.”<br />

In 2009, at age thirty-nine, he was<br />

arrested for selling cocaine. He hired<br />

a friend of a friend’s lawyer, who was<br />

Yemeni.<br />

But at the time neither Peter nor<br />

his attorney knew that something important<br />

had changed in the nineteen<br />

years since his 1990 felony for armed<br />

robbery. “Janet Reno changed the law<br />

back in ’98,” he says. “If you’re not<br />

a citizen and catch a felony, you are<br />

deportable.” He felt a rush of fear as<br />

this fact emerged during the prosecution’s<br />

remarks at the hearing. Serving<br />

more time in a U.S. prison was a very<br />

unpleasant prospect but was nothing<br />

compared to being deported to<br />

Iraq as a fair-skinned Chaldean who’d<br />

spent decades steeped in U.S. culture.<br />

He didn’t know Arabic, and he didn’t<br />

know anyone in Iraq. Deportation was<br />

effectively a death sentence. Even if<br />

actually being deported was unheard<br />

of, he didn’t want to be put on that list.<br />

During the court recess, Peter sat at<br />

the wooden defendant’s table next to<br />

his Yemini attorney, who raised his eyebrows<br />

and leaned toward Peter’s ear.<br />

Get out, he said.<br />

“He looked at me. He told me,<br />

‘They’re going to lock you up. Send<br />

you back.’ I remember that day. Wow.<br />

How he looked at me. He said ‘Run.’<br />

And with my, with my dumbness, I believed<br />

him. I hate to admit it. It’s nuts.<br />

I got up and left. My lawyer said to run,<br />

and my dumb ass ran.”<br />

When the court recessed, Peter just<br />

walked out and went home. Not for<br />

long, though. “It took them a month or<br />

two to come get me. ICE came, and I<br />

was in for three months, but then the<br />

policy with Iraq was that they wouldn’t<br />

deport me.” That would change.<br />

Immigration and Naturalization<br />

Services arrested Peter in 2009, and<br />

he served three months in the Calhoun<br />

County Jail in Battle Creek. His trial<br />

for the drug charge proceeded – this<br />

time with a public defender after he<br />

parted ways with the Yemini attorney.<br />

In January of 2011, he was sentenced to<br />

thirty-two months in prison and four<br />

years of probation. He served about<br />

thirty months in state prison. After<br />

his release, he reported to ICE every<br />

six months. Like all Iraqi immigrants<br />

with final orders of deportation, he<br />

was assigned an immigration officer<br />

whose job was to check up with an<br />

individuals’ employment and housing<br />

situations and monitor them to be<br />

sure they were accountable, with no<br />

criminal activity. They could be hard.<br />

“The ICE people, I’ve never seen anything<br />

like it,” Peter says. “A few are<br />

okay, normal. Most of them, it seems<br />

like they’re there because they want<br />

to show you their power, to disrespect<br />

you. They call you liar, call you piece<br />

of shit, Arab.”<br />

Peter worked for a disaster cleanup<br />

company at the time, entering homes<br />

and businesses after destructive<br />

events such as fires and floods, and<br />

even crimes. “We would go to burnt,<br />

damaged properties, water-damaged<br />

properties, and we’d tear them down<br />

and rebuild them,” he says.<br />

His boss would put him on the<br />

phone or in front of customers whenever<br />

possible because, he says, he was<br />

the friendliest, most outgoing man on<br />

the crew. His boss wrote a letter in support<br />

of his release in 2018, telling the<br />

immigration court that Peter is “hardworking,<br />

trustworthy, a team player,<br />

and a huge asset to our organization.<br />

He has always been reliable…we continually<br />

receive positive comments<br />

about his work ethic and personality<br />

from many of our clients.”<br />

Because of his light skin and red<br />

hair, Peter says, co-workers often took<br />

“The ICE people, I’ve never seen anything like it,” Peter says. “A few<br />

are okay, normal. Most of them, it seems like they’re there because<br />

they want to show you their power, to disrespect you.”<br />

it for granted he was white. A surprising<br />

number of them, he says, were allied<br />

with white supremacy groups and<br />

assumed that he’d be sympathetic. He<br />

wasn’t. “They thought I was thinking<br />

the same way, so they’d say things<br />

about the Hispanic people, about Jewish<br />

people. They hate Jewish people<br />

more than anything.”<br />

“They’re all thinking it’s going to<br />

be a race war,” Peter said. He makes an<br />

upside-down “okay” hand gesture, now<br />

associated with white supremacists,<br />

and says, “This is how they identify<br />

each other, how they say white power.<br />

They’re signaling.” They sometimes signaled<br />

him that way, Peter said, because<br />

of his looks. “I’m thinking, Honest to<br />

God, this is everywhere. This is ugly.”<br />

Peter has been married to Mimi<br />

since 1999. (For her privacy and Peter’s,<br />

Mimi is not her real name.) She’s<br />

also from a Chaldean family, though<br />

she was born in Detroit, and she is<br />

kind and beautiful, with long hair and<br />

a wide-open smile. The couple tried<br />

for a baby, and she miscarried several<br />

times. Years passed. They adopted<br />

dogs. Mimi worked in a hair salon and<br />

started a cookie business. In 2015, a<br />

ON THE RUN continued on page 41<br />

24 CHALDEAN NEWS <strong>SEPTEMBER</strong> <strong>2022</strong>