You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

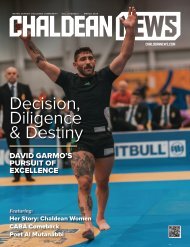

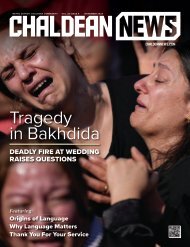

COVER STORY<br />

ON THE RUN continued from page 20<br />

By mid-afternoon on June 11, 2017,<br />

the Detroit ICE office was filled with<br />

recently-arrested men. Detroit-area<br />

Iraqi families were urgently trying<br />

to reach one another and warn them<br />

about the surprise raid. Peter Abbo<br />

was out on an errand when his wife<br />

Mimi answered their door. She called<br />

him. According to a letter she sent immigration<br />

count, he “…turned himself<br />

in within ten minutes of getting my<br />

phone call. [He] would never run away<br />

from his situation and never has.” Peter<br />

and Mimi were both aware of the<br />

other Detroit arrests that day. “I knew<br />

what was happening. I could have<br />

run,” he said. “I faced up to it.”<br />

He came home and ICE agents<br />

waiting there arrested him.<br />

It seemed reasonable to Peter Abbo<br />

that his situation could be sorted out.<br />

He did not have a violent past. He was<br />

involved in a weird and spontaneous<br />

armed robbery in 1990 and a cocaine<br />

deal in 2009, but had served time years<br />

ago for both. He had scrupulously kept<br />

up with ICE check-in appointments, even<br />

as the appointments had become more<br />

tense and punitive since Donald Trump<br />

had taken office six months before.<br />

The day after the 2016 election that<br />

brought Trump the presidency, Peter<br />

remembers, he had a scheduled meeting<br />

with his immigration officer. He<br />

was in the waiting room with several<br />

other people when his officer called<br />

out across the room: “Hey Peter, did<br />

you hear Trump won? All you guys are<br />

going to get deported now.”<br />

Peter chose not to answer. He<br />

looked down and shook his head.<br />

With a thick Michigan accent, elongating<br />

the first “a” in “Arabs,” the officer<br />

said, “All you A-rabs. Wait and<br />

see.”<br />

More than half of the Iraqis arrested<br />

and threatened with deportation<br />

in 2017 are neither Arab nor Muslim.<br />

Peter is Chaldean, a sect of Catholicism.<br />

He grew up speaking Aramaic,<br />

not Arabic. A minority group in Iraq,<br />

the Chaldean community has endured<br />

an epic list of injustices through history,<br />

from its formation in the Mesopotamian<br />

era to the present. Ostracized<br />

and in danger in Iraq, Chaldeans are<br />

the primary subset of all Iraqi immigrants<br />

to the U.S. The first influx<br />

began around 1914 when Henry Ford<br />

offered appealing wages of $5 a day<br />

for autoworkers. As generations of suffering<br />

followed for Chaldeans in Iraq,<br />

they continued to slowly immigrate<br />

to the Detroit area. At least 250,000<br />

Iraqis are known to have died at the<br />

hand of their own government during<br />

Saddam Hussein’s brutal twenty-fouryear<br />

reign. And Chaldeans’ suffering<br />

didn’t end with Saddam’s death in<br />

2006. Thirteen years later, in 2019, the<br />

Chaldean archbishop announced that<br />

Iraqi Christians faced “extinction” unless<br />

there was a change in the political<br />

situation.<br />

Peter and his twin brother were<br />

born in 1969 in Baghdad. The Abbos<br />

had come from a village in northernmost<br />

Iraq, near the borders of Iran<br />

and Turkey. Red-headed, fair-skinned<br />

people—like Peter and his twin—are<br />

common there, and Chaldean culture<br />

is dominant. Peter tells me that during<br />

World War I his family and his village<br />

helped the Russians and, as a result,<br />

“The rest of Iraq has always treated us<br />

as traitors.” His parents were forced to<br />

move south when the violence against<br />

Christians became intolerable. “Kidnapping<br />

and killing Christians happened<br />

so much,” he said.<br />

His parents thought they’d be safer<br />

in the city, but living there was substantially<br />

worse. In the north, the Abbos<br />

had been almost exclusively among<br />

Chaldeans, but in Baghdad they were<br />

a minority. The family spoke Aramaic<br />

at home. Everyone around them spoke<br />

Arabic, and most were Muslim. Peter<br />

couldn’t get his footing in school because<br />

of the language difference. His<br />

sister was harassed because she didn’t<br />

wear a hijab. The children were bullied,<br />

and Peter has a bright white scar<br />

on his forehead from an injury sustained<br />

during that time. He touches<br />

it when he talks about those years in<br />

Baghdad. “They jumped me,” he says<br />

quietly. “They threw rocks.”<br />

In 1980 the Iran-Iraq War began.<br />

The same year, doctors told Peter’s father<br />

that he needed a pacemaker. Fortunately<br />

for the family, his father became<br />

eligible for a visa to have surgery<br />

in the U.S. It would also allow his wife<br />

and children a respite from the day-today<br />

brutality they were facing.<br />

Peter and his twin brother were<br />

both given traditional Chaldean<br />

names when they were born, but when<br />

they moved to America, they took<br />

their baptismal names. They learned<br />

English. Their father recovered, then<br />

began working as a cook for a suburban<br />

Detroit banquet hall. Peter’s older<br />

sister married and had children. Four<br />

years passed. The Abbos overstayed<br />

their visitor visa, and, in 1984, left the<br />

country in order to re-enter later using<br />

proper immigration channels.<br />

Returning to Iraq in the interim was<br />

not possible. Peter’s oldest brother<br />

– the only immediate family member<br />

to have stayed behind – was by 1984<br />

in his fourth year as a soldier in the<br />

Iran-Iraq War. It became known in his<br />

army unit that his family had moved to<br />

the U.S.—an unforgivable stain on his<br />

name. Anyone traveling to America,<br />

and especially coming back to Iraq after<br />

living in America, was assumed to<br />

be involved in espionage. His brother<br />

learned of a secret and credible plan<br />

for his fellow soldiers to torture and<br />

kill him; he absconded instead, running<br />

into the mountainous wilderness<br />

near their home village and surviving<br />

on little until he arrived in an Iranian<br />

refugee camp.<br />

To avoid endangering other family<br />

members or risk torture and death<br />

themselves, Peter and his family<br />

moved to Casablanca in 1984, living<br />

off of their small savings. His now-naturalized<br />

adult sister sponsored their<br />

re-entry to the U.S. in 1986, when Peter<br />

was seventeen.<br />

The Abbos moved to Detroit’s Chaldean<br />

Town, near 7 Mile and Woodward<br />

Avenue, a neighborhood of densely<br />

packed single-family houses without<br />

driveways—built before cars—and a<br />

small strip of Iraqi bakeries and meat<br />

markets. Of the roughly 640,000 Chaldeans<br />

worldwide, about 120,000 reside<br />

in Metro Detroit. Saddam’s rule<br />

had prompted thousands of Chaldean<br />

families to flee persecution in Iraq beginning<br />

in the late 1970s. Many went<br />

to Detroit, and a large number of them<br />

settled into jobs operating corner convenience<br />

stores as family businesses,<br />

as they had done in Iraq. Living in a<br />

contemporary food desert, many Detroit<br />

residents rely on corner stores<br />

for nutrition. The Chaldean Chamber<br />

of Commerce says that nine out of ten<br />

food stores in the city are owned by<br />

Chaldeans. Muslims are forbidden to<br />

buy and sell alcohol, creating a business<br />

niche for Chaldeans both in Iraq<br />

More than half of the Iraqis arrested and threatened with deportation<br />

in 2017 are neither Arab nor Muslim… the Chaldean community has<br />

endured an epic list of injustices through history, from its formation<br />

in the Mesopotamian era to the present.<br />

and in the U.S. Chaldeans and their<br />

late-night liquor stores, called party<br />

stores here, are stalwarts of Detroit<br />

culture. Like bodegas in New York,<br />

party stores in Detroit are handy for<br />

beer or milk or toiletries, and a reliable<br />

source of friendly conversation. I spent<br />

an afternoon in a West Side Detroit<br />

party store in 2019 and its Chaldean<br />

owner, who himself spent ten months<br />

detained in 2017-18, greeted everyone<br />

who entered by name, usually referencing<br />

their family. “Terry, we got diapers<br />

in for your sister’s baby,” he told<br />

one visitor.<br />

In the mid-80s, when Peter was a<br />

teenager, Pershing High School, on<br />

Detroit’s West Side, proved even less<br />

welcoming than Baghdad had been.<br />

Detroit is a majority Black city. Most<br />

other Middle Eastern kids—who were<br />

generally Muslim and had immigrated<br />

to Dearborn, adjacent to Detroit—had<br />

olive skin and dark hair. Peter was<br />

freckled and pale, ginger-haired. Peter<br />

said he tried at school and tried not to<br />

get distracted by various criminal activities<br />

in his neighborhood. “But my<br />

head wasn’t in place.”<br />

He was working after school and at<br />

ON THE RUN continued on page 24<br />

22 CHALDEAN NEWS <strong>SEPTEMBER</strong> <strong>2022</strong>