byronchild - logo

byronchild - logo

byronchild - logo

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

manhood<br />

When I first met Peter he said,<br />

‘I claim you, boy.’ I didn’t really<br />

know what he was talking about.<br />

A year later or so on another trip<br />

he claimed me. He said, ‘I will be<br />

your father. I will be piepa.’ With<br />

all the other elders there he made<br />

his statement. They all named<br />

their places where they were in<br />

my life. It was 1984; I knew what<br />

it meant.<br />

Peter is impeccable to me as<br />

a father. I do what he says. In<br />

Aboriginal culture there is jilli<br />

binna. It means look and listen.<br />

There is no mouth in it, just be<br />

quiet and look and listen and learn<br />

by watching.<br />

Talking straight up about it,<br />

my birth father was a violent man,<br />

angsty man. Ain’t no shit about<br />

it. He made up for that before<br />

he passed away. In some way he<br />

had remorse and apologised as<br />

he got older. I got some understanding<br />

and we parted — he left<br />

this planet and then Peter Costello<br />

(Makrrnggal) claimed me. And I<br />

had this other father. In Aboriginal,<br />

this is my brother, they’re not like<br />

my brothers, they are my brothers.<br />

This man is not like my father, he<br />

is my father — it’s a big difference.<br />

I am his son. This father of<br />

mine is such a gentle, kind man<br />

you know. His traditions, his<br />

Aboriginality, shines — his connections<br />

to the land. He’ll sit out<br />

on the verandah and laugh his<br />

head off — ‘Ha-ha the birds are<br />

having a funny talk.’ I sat down<br />

and listened with him and we<br />

both started laughing, listening to the<br />

birds talk. That simple little thing, he<br />

got me listening, taking notice of the<br />

birds. It was so beautiful, sitting there<br />

with my dad listening and laughing<br />

with the birds, joining in their joy — so<br />

beautiful.<br />

I had to apologise to my birth father<br />

after he died, because he said he was<br />

sorry just before he died. I didn’t say<br />

sorry to him. I was violent to my father.<br />

You know how I was violent? When<br />

my father said I was a good father, you<br />

know what I said? ‘Yeah I never hit<br />

him once.’ I didn’t say, ‘Thanks, dad,<br />

I’m trying.’ I’d have liked to have had<br />

the softness in my heart to have said,<br />

‘Thanks, dad, I am trying to come from<br />

love.’ I was violent in a different form<br />

— I didn’t allow him to love me like he<br />

wanted to. I wouldn’t let him.<br />

I saw him bash the shit out of my<br />

<strong>byronchild</strong> 40<br />

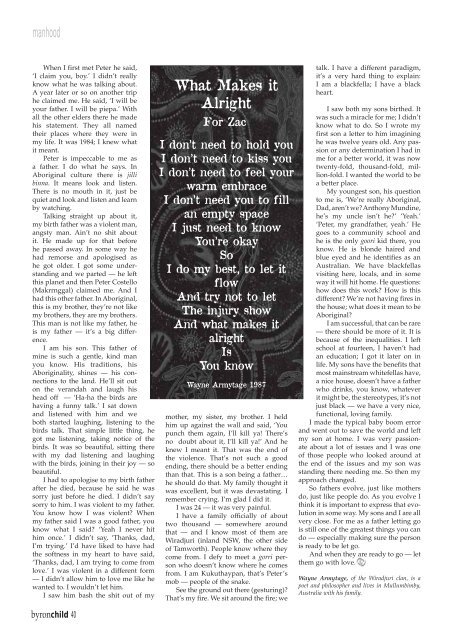

What Makes it<br />

Alright<br />

For Zac<br />

I don’t need to hold you<br />

I don’t need to kiss you<br />

I don’t need to feel your<br />

warm embrace<br />

I don’t need you to fill<br />

an empty space<br />

I just need to know<br />

You’re okay<br />

So<br />

I do my best, to let it<br />

flow<br />

And try not to let<br />

The injury show<br />

And what makes it<br />

alright<br />

Is<br />

You know<br />

Wayne Armytage 1987<br />

mother, my sister, my brother. I held<br />

him up against the wall and said, ‘You<br />

punch them again, I’ll kill ya! There’s<br />

no doubt about it, I’ll kill ya!’ And he<br />

knew I meant it. That was the end of<br />

the violence. That’s not such a good<br />

ending, there should be a better ending<br />

than that. This is a son being a father…<br />

he should do that. My family thought it<br />

was excellent, but it was devastating. I<br />

remember crying. I’m glad I did it.<br />

I was 24 — it was very painful.<br />

I have a family officially of about<br />

two thousand — somewhere around<br />

that — and I know most of them are<br />

Wiradjuri (inland NSW, the other side<br />

of Tamworth). People know where they<br />

come from. I defy to meet a gorri person<br />

who doesn’t know where he comes<br />

from. I am Kukuthaypan, that’s Peter’s<br />

mob — people of the snake.<br />

See the ground out there (gesturing)?<br />

That’s my fire. We sit around the fire; we<br />

talk. I have a different paradigm,<br />

it’s a very hard thing to explain:<br />

I am a blackfella; I have a black<br />

heart.<br />

I saw both my sons birthed. It<br />

was such a miracle for me; I didn’t<br />

know what to do. So I wrote my<br />

first son a letter to him imagining<br />

he was twelve years old. Any passion<br />

or any determination I had in<br />

me for a better world, it was now<br />

twenty-fold, thousand-fold, million-fold.<br />

I wanted the world to be<br />

a better place.<br />

My youngest son, his question<br />

to me is, ‘We’re really Aboriginal,<br />

Dad, aren’t we? Anthony Mundine,<br />

he’s my uncle isn’t he?’ ‘Yeah.’<br />

‘Peter, my grandfather, yeah.’ He<br />

goes to a community school and<br />

he is the only goori kid there, you<br />

know. He is blonde haired and<br />

blue eyed and he identifies as an<br />

Australian. We have blackfellas<br />

visiting here, locals, and in some<br />

way it will hit home. He questions:<br />

how does this work? How is this<br />

different? We’re not having fires in<br />

the house; what does it mean to be<br />

Aboriginal?<br />

I am successful, that can be rare<br />

— there should be more of it. It is<br />

because of the inequalities. I left<br />

school at fourteen, I haven’t had<br />

an education; I got it later on in<br />

life. My sons have the benefits that<br />

most mainstream whitefellas have,<br />

a nice house, doesn’t have a father<br />

who drinks, you know, whatever<br />

it might be, the stereotypes, it’s not<br />

just black — we have a very nice,<br />

functional, loving family.<br />

I made the typical baby boom error<br />

and went out to save the world and left<br />

my son at home. I was very passionate<br />

about a lot of issues and I was one<br />

of those people who looked around at<br />

the end of the issues and my son was<br />

standing there needing me. So then my<br />

approach changed.<br />

So fathers evolve, just like mothers<br />

do, just like people do. As you evolve I<br />

think it is important to express that evolution<br />

in some way. My sons and I are all<br />

very close. For me as a father letting go<br />

is still one of the greatest things you can<br />

do — especially making sure the person<br />

is ready to be let go.<br />

And when they are ready to go — let<br />

them go with love.<br />

Wayne Armytage, of the Wiradjuri clan, is a<br />

poet and philosopher and lives in Mullumbimby,<br />

Australia with his family.