The Folk Biology of the Tobelo People - Smithsonian Institution ...

The Folk Biology of the Tobelo People - Smithsonian Institution ...

The Folk Biology of the Tobelo People - Smithsonian Institution ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

NUMBER 34 29<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> referent to require a change in <strong>the</strong><br />

attributive" (Berlin et al., 1974:51). In this test one asks<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r "blackbirds" and "white oaks," for example, would<br />

still be "blackbirds" and "white oaks" if tiiey were painted red.<br />

So, we may conclude tiiat <strong>the</strong> words or phrases might be<br />

lexemic. <strong>Tobelo</strong> may similarly be asked about descriptive<br />

phrases used to disambiguate "totaleo." If, for example, a<br />

(chicken) flies or lives untended in die jungle, is it still a<br />

'(chicken) we feed' or '(chicken) we tend'? <strong>The</strong>y sometimes<br />

answer yes—though both expressions are not lexemic—<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y are trying to make us understand that <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

distinguishing two classes <strong>of</strong> animal, ra<strong>the</strong>r than just distinguishing<br />

"<strong>the</strong> class <strong>of</strong> aU birds that can fly" from "<strong>the</strong> class <strong>of</strong><br />

all birds which we feed." Otiiers may try to be more helpful or<br />

explanatory, saying, "WeU, it lives untended in <strong>the</strong> jungle but<br />

it's just it, <strong>the</strong> (chicken/bird), but we don't tend it anymore; we<br />

would tend it but it..." and so on. <strong>The</strong>y are trying to make die<br />

etiinographer understand tiiat <strong>the</strong>y are distinguishing two<br />

classes <strong>of</strong> animal (birds and chickens), which botii happen to be<br />

labeled by die same form totaleo in <strong>the</strong>ir language. <strong>The</strong> phrases<br />

are not lexemic, but nei<strong>the</strong>r do tiiey just distinguish two logical<br />

sets, '<strong>the</strong> set <strong>of</strong> aU birds that regularly fly' from '<strong>the</strong> set <strong>of</strong> aU<br />

birds which we feed.'<br />

In otiier cases where similar markedness occurs, <strong>the</strong><br />

non-lexemic descriptive phrase to disambiguate die lower-level<br />

unmarked form is almost "implied" by die marked form. Thus<br />

tf <strong>the</strong> marked one <strong>of</strong> two subclasses is referred to as "die jungle<br />

X," die unmarked subclass "X^' witii which it contrasts may<br />

reliably be disambiguated from die higher-level "Xx" using an<br />

attributive which is die local "opposite" <strong>of</strong> 'jungle' (such as<br />

'shore').<br />

It might seem tiiat since tiiese "opposite" characteristics are<br />

usually predictable, tiiere is no reason to distinguish predictable<br />

and reliable expressions from lexemic (tiiough unmarked)<br />

terms. Yet any analysis mat fails to distinguish such "predictable<br />

and reliable" expressions from truly lexemic terms implies<br />

mat some unified definition <strong>of</strong> those expressions could be<br />

found. In fact <strong>the</strong> only common defining feature such<br />

expressions may have when tiiey are applied to disambiguate so<br />

many unmarked classes is that <strong>the</strong>y are not <strong>the</strong> attributive<br />

locally considered tiiat expression's "opposite." Thus informants<br />

may say that a plant type "X" is subdivided into "<strong>the</strong> red<br />

X" and "<strong>the</strong> white X." On die one hand, "red" might here be an<br />

attributive because some part <strong>of</strong> die plant or animal so<br />

designated is in fact reddish in color. But it might also be given<br />

as an attributive to disambiguate a polysemous, unmarked "X"<br />

term, simply because die otiier subclass with which "red X"<br />

contrasts is called "white X" (perhaps because <strong>of</strong> exceptionally<br />

light coloration <strong>of</strong> plants in tiiat subclass), and "red" is locaUy<br />

die most likely opposite <strong>of</strong> "white." <strong>The</strong> alternative interpretations<br />

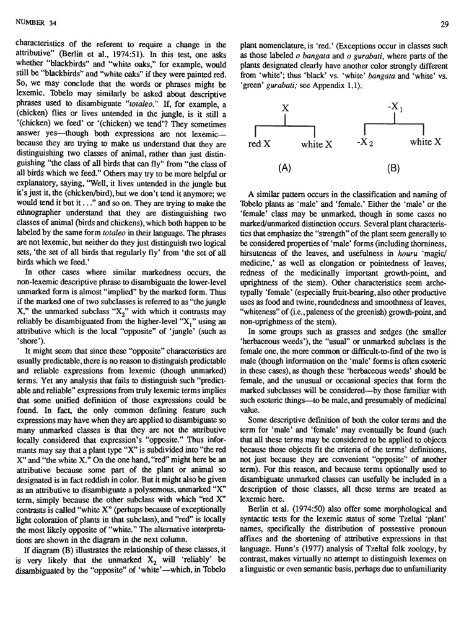

are shown in die diagram in die next column.<br />

If diagram (B) iUustrates <strong>the</strong> relationship <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se classes, it<br />

is very likely that <strong>the</strong> unmarked X2 wiU 'reliably' be<br />

disambiguated by <strong>the</strong> "opposite" <strong>of</strong> 'white'—which, in <strong>Tobelo</strong><br />

plant nomenclature, is 'red.' (Exceptions occur in classes such<br />

as those labeled o bangata and o gurabati, where parts <strong>of</strong> die<br />

plants designated clearly have anotiier color strongly different<br />

from 'white'; thus 'black' vs. 'white' bangata and 'white' vs.<br />

'green' gurabati; see Appendix 1.1).<br />

X<br />

-X<br />

redX white X -x2 white X<br />

(A) (B)<br />

A similar pattern occurs in die classification and naming <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Tobelo</strong> plants as 'male' and 'female.' Eitiier <strong>the</strong> 'male' or die<br />

'female' class may be unmarked, though in some cases no<br />

marked/unmarked distinction occurs. Several plant characteristics<br />

tiiat emphasize <strong>the</strong> "strength" <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plant seem generaUy to<br />

be considered properties <strong>of</strong> 'male' forms (including thorniness,<br />

hirsuteness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> leaves, and usefulness in houru 'magic/<br />

medicine,' as well as elongation or pointedness <strong>of</strong> leaves,<br />

redness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> medicinaUy important growtii-point, and<br />

uprightness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stem). O<strong>the</strong>r characteristics seem archetypally<br />

'female' (especiaUy fruit-bearing, also o<strong>the</strong>r productive<br />

uses as food and twine, roundedness and smoothness <strong>of</strong> leaves,<br />

"whiteness" <strong>of</strong> (i.e., paleness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> greenish) growth-point, and<br />

non-uprightness <strong>of</strong> die stem).<br />

In some groups such as grasses and sedges (die smaller<br />

'herbaceous weeds'), die "usual" or unmarked subclass is die<br />

female one, die more common or difficult-to-find <strong>of</strong> die two is<br />

male (tiiough information on <strong>the</strong> 'male' forms is <strong>of</strong>ten esoteric<br />

in tiiese cases), as tiiough <strong>the</strong>se 'herbaceous weeds' should be<br />

female, and die unusual or occasional species that form die<br />

marked subclasses wUl be considered—by tiiose famUiar with<br />

such esoteric tilings—to be male, and presumably <strong>of</strong> medicinal<br />

value.<br />

Some descriptive definition <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> color terms and die<br />

term for 'male' and 'female' may eventually be found (such<br />

tiiat aU <strong>the</strong>se terms may be considered to be applied to objects<br />

because tiiose objects fit die criteria <strong>of</strong> die terms' definitions,<br />

not just because tiiey are convenient "opposite" <strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

term). For this reason, and because terms optionally used to<br />

disambiguate unmarked classes can usefully be included in a<br />

description <strong>of</strong> those classes, all <strong>the</strong>se terms are treated as<br />

lexemic here.<br />

Berlin et al. (1974:50) also <strong>of</strong>fer some morphological and<br />

syntactic tests for <strong>the</strong> lexemic status <strong>of</strong> some Tzeltal 'plant'<br />

names, specifically <strong>the</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> possessive pronoun<br />

affixes and die shortening <strong>of</strong> attributive expressions in that<br />

language. Hunn's (1977) analysis <strong>of</strong> Tzeltal folk zoology, by<br />

contrast makes virtuaUy no attempt to distinguish lexemes on<br />

a linguistic or even semantic basis, perhaps due to unfamiliarity