NaraNjo-Sa'al - World Monuments Fund

NaraNjo-Sa'al - World Monuments Fund

NaraNjo-Sa'al - World Monuments Fund

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

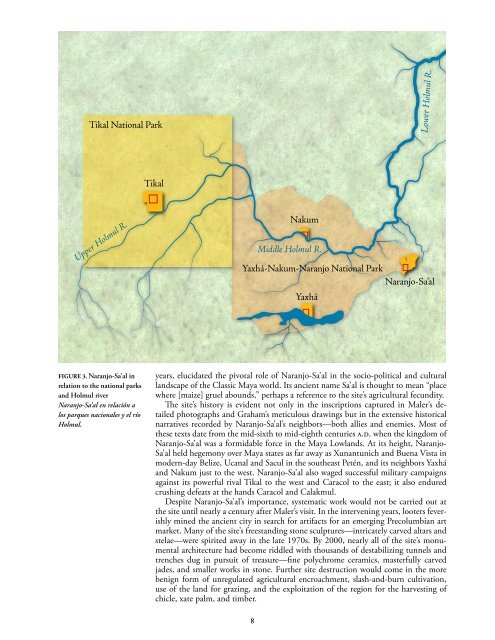

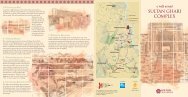

Tikal National Park<br />

Upper Holmul R.<br />

Figure 3. Naranjo-Sa’al in<br />

relation to the national parks<br />

and Holmul river<br />

Naranjo-Sa’al en relación a<br />

los parques nacionales y el río<br />

Holmul.<br />

Tikal<br />

Yaxhá-Nakum-Naranjo National Park<br />

Naranjo-Sa’al<br />

Yaxhá<br />

years, elucidated the pivotal role of Naranjo-Sa’al in the socio-political and cultural<br />

landscape of the Classic Maya world. Its ancient name Sa’al is thought to mean “place<br />

where [maize] gruel abounds,” perhaps a reference to the site’s agricultural fecundity.<br />

The site’s history is evident not only in the inscriptions captured in Maler’s detailed<br />

photographs and Graham’s meticulous drawings but in the extensive historical<br />

narratives recorded by Naranjo-Sa’al’s neighbors—both allies and enemies. Most of<br />

these texts date from the mid-sixth to mid-eighth centuries a.d. when the kingdom of<br />

Naranjo-Sa’al was a formidable force in the Maya Lowlands. At its height, Naranjo-<br />

Sa’al held hegemony over Maya states as far away as Xunantunich and Buena Vista in<br />

modern-day Belize, Ucanal and Sacul in the southeast Petén, and its neighbors Yaxhá<br />

and Nakum just to the west. Naranjo-Sa’al also waged successful military campaigns<br />

against its powerful rival Tikal to the west and Caracol to the east; it also endured<br />

crushing defeats at the hands Caracol and Calakmul.<br />

Despite Naranjo-Sa’al’s importance, systematic work would not be carried out at<br />

the site until nearly a century after Maler’s visit. In the intervening years, looters feverishly<br />

mined the ancient city in search for artifacts for an emerging Precolumbian art<br />

market. Many of the site’s freestanding stone sculptures—intricately carved altars and<br />

stelae—were spirited away in the late 1970s. By 2000, nearly all of the site’s monumental<br />

architecture had become riddled with thousands of destabilizing tunnels and<br />

trenches dug in pursuit of treasure—fine polychrome ceramics, masterfully carved<br />

jades, and smaller works in stone. Further site destruction would come in the more<br />

benign form of unregulated agricultural encroachment, slash-and-burn cultivation,<br />

use of the land for grazing, and the exploitation of the region for the harvesting of<br />

chicle, xate palm, and timber.<br />

8<br />

Nakum<br />

Middle Holmul R.<br />

Lower Holmul R.