Operational tools and adaptive management

Operational tools and adaptive management

Operational tools and adaptive management

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

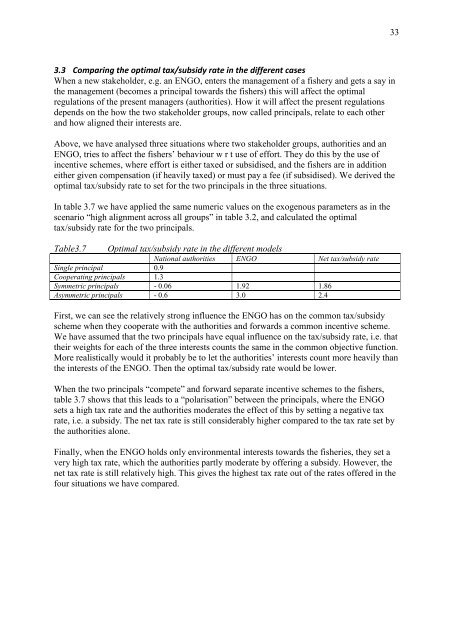

3.3 Comparing the optimal tax/subsidy rate in the different cases<br />

When a new stakeholder, e.g. an ENGO, enters the <strong>management</strong> of a fishery <strong>and</strong> gets a say in<br />

the <strong>management</strong> (becomes a principal towards the fishers) this will affect the optimal<br />

regulations of the present managers (authorities). How it will affect the present regulations<br />

depends on the how the two stakeholder groups, now called principals, relate to each other<br />

<strong>and</strong> how aligned their interests are.<br />

Above, we have analysed three situations where two stakeholder groups, authorities <strong>and</strong> an<br />

ENGO, tries to affect the fishers‟ behaviour w r t use of effort. They do this by the use of<br />

incentive schemes, where effort is either taxed or subsidised, <strong>and</strong> the fishers are in addition<br />

either given compensation (if heavily taxed) or must pay a fee (if subsidised). We derived the<br />

optimal tax/subsidy rate to set for the two principals in the three situations.<br />

In table 3.7 we have applied the same numeric values on the exogenous parameters as in the<br />

scenario “high alignment across all groups” in table 3.2, <strong>and</strong> calculated the optimal<br />

tax/subsidy rate for the two principals.<br />

Table3.7 Optimal tax/subsidy rate in the different models<br />

National authorities ENGO Net tax/subsidy rate<br />

Single principal 0.9<br />

Cooperating principals 1.3<br />

Symmetric principals - 0.06 1.92 1.86<br />

Asymmetric principals - 0.6 3.0 2.4<br />

First, we can see the relatively strong influence the ENGO has on the common tax/subsidy<br />

scheme when they cooperate with the authorities <strong>and</strong> forwards a common incentive scheme.<br />

We have assumed that the two principals have equal influence on the tax/subsidy rate, i.e. that<br />

their weights for each of the three interests counts the same in the common objective function.<br />

More realistically would it probably be to let the authorities‟ interests count more heavily than<br />

the interests of the ENGO. Then the optimal tax/subsidy rate would be lower.<br />

When the two principals “compete” <strong>and</strong> forward separate incentive schemes to the fishers,<br />

table 3.7 shows that this leads to a “polarisation” between the principals, where the ENGO<br />

sets a high tax rate <strong>and</strong> the authorities moderates the effect of this by setting a negative tax<br />

rate, i.e. a subsidy. The net tax rate is still considerably higher compared to the tax rate set by<br />

the authorities alone.<br />

Finally, when the ENGO holds only environmental interests towards the fisheries, they set a<br />

very high tax rate, which the authorities partly moderate by offering a subsidy. However, the<br />

net tax rate is still relatively high. This gives the highest tax rate out of the rates offered in the<br />

four situations we have compared.<br />

33