Minimality Effects in Syntax · The MLC and Derivational Economy ...

Minimality Effects in Syntax · The MLC and Derivational Economy ...

Minimality Effects in Syntax · The MLC and Derivational Economy ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

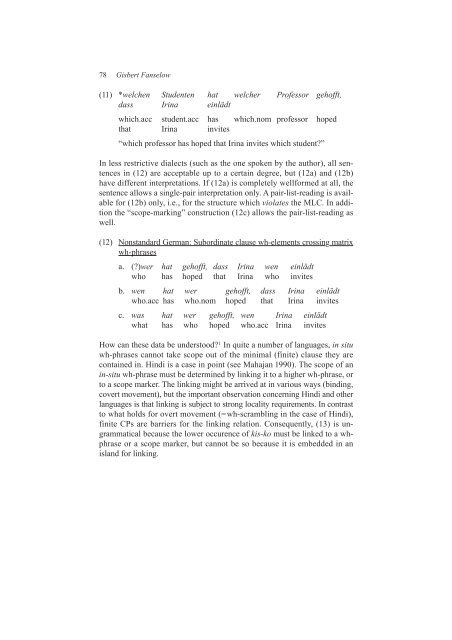

78 Gisbert Fanselow<br />

(11) *welchen Studenten hat welcher Professor gehofft,<br />

dass Ir<strong>in</strong>a e<strong>in</strong>lädt<br />

which.acc student.acc has which.nom professor hoped<br />

that Ir<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong>vites<br />

“which professor has hoped that Ir<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong>vites which student?”<br />

In less restrictive dialects (such as the one spoken by the author), all sentences<br />

<strong>in</strong> (12) are acceptable up to a certa<strong>in</strong> degree, but (12a) <strong>and</strong> (12b)<br />

have different <strong>in</strong>terpretations. If (12a) is completely wellformed at all, the<br />

sentence allows a s<strong>in</strong>gle-pair <strong>in</strong>terpretation only. A pair-list-read<strong>in</strong>g is available<br />

for (12b) only, i.e., for the structure which violates the <strong>MLC</strong>. In addition<br />

the “scope-mark<strong>in</strong>g” construction (12c) allows the pair-list-read<strong>in</strong>g as<br />

well.<br />

(12) Nonst<strong>and</strong>ard German: Subord<strong>in</strong>ate clause wh-elements cross<strong>in</strong>g matrix<br />

wh-phrases<br />

a.(?)wer hat gehofft, dass Ir<strong>in</strong>a wen e<strong>in</strong>lädt<br />

who has hoped that Ir<strong>in</strong>a who <strong>in</strong>vites<br />

b. wen hat wer gehofft, dass Ir<strong>in</strong>a e<strong>in</strong>lädt<br />

who.acc has who.nom hoped that Ir<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong>vites<br />

c. was hat wer gehofft, wen Ir<strong>in</strong>a e<strong>in</strong>lädt<br />

what has who hoped who.acc Ir<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong>vites<br />

How can these data be understood? 1 In quite a number of languages, <strong>in</strong> situ<br />

wh-phrases cannot take scope out of the m<strong>in</strong>imal (f<strong>in</strong>ite) clause they are<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>. H<strong>in</strong>di is a case <strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t (see Mahajan 1990). <strong>The</strong> scope of an<br />

<strong>in</strong>-situ wh-phrase must be determ<strong>in</strong>ed by l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g it to a higher wh-phrase, or<br />

to a scope marker. <strong>The</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g might be arrived at <strong>in</strong> various ways (b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

covert movement), but the important observation concern<strong>in</strong>g H<strong>in</strong>di <strong>and</strong> other<br />

languages is that l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g is subject to strong locality requirements. In contrast<br />

to what holds for overt movement (=wh-scrambl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the case of H<strong>in</strong>di),<br />

f<strong>in</strong>ite CPs are barriers for the l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g relation. Consequently, (13) is ungrammatical<br />

because the lower occurence of kis-ko must be l<strong>in</strong>ked to a whphrase<br />

or a scope marker, but cannot be so because it is embedded <strong>in</strong> an<br />

isl<strong>and</strong> for l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g.