Determinants of Emotional Experiences in Traffic Situations ... - OPUS

Determinants of Emotional Experiences in Traffic Situations ... - OPUS

Determinants of Emotional Experiences in Traffic Situations ... - OPUS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Introduction 13<br />

(Deffenbacher et al., 2001; Björklund, 2008; Lajunen & Parker, 2001). Hostile gestures, impeded<br />

progress or the reckless driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> others are salient characteristics that can trigger an anger response<br />

<strong>in</strong> a traffic situation (Deffenbacher et al., 1994). The characteristics <strong>of</strong> the driver, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g age<br />

(Björklund, 2008), driv<strong>in</strong>g experience (Lajunen & Parker, 2001) or driv<strong>in</strong>g motivation (Philippe et al.,<br />

2009), could moderate the <strong>in</strong>tensity <strong>of</strong> the anger experience. The end result could be <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

aggressive and risky driv<strong>in</strong>g, the most thoroughly exam<strong>in</strong>ed l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>in</strong> the proposed model (Nesbit,<br />

Conger & Conger, 2007). One reason for this strong focus might be the straightforward assumption<br />

that angry people drive aggressive and recklessly, caus<strong>in</strong>g more dangerous situations (Dahlen, Mart<strong>in</strong>,<br />

Ragan & Kuhlmann, 2005; Schwebel et al., 2006). Indeed, the l<strong>in</strong>k between anger and <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

driv<strong>in</strong>g speeds and reduced time-to-collisions (TTC) has been repeatedly reported (Deffenbacher,<br />

Lynch, Oett<strong>in</strong>g & Swaim, 2002; Matthews et al., 1998; Mesken et al., 2007). The decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

performance is sometimes attributed to a maladaptive attention shift away from important visual<br />

features <strong>of</strong> the environment (Cai & L<strong>in</strong>, 2011) and the change <strong>in</strong> risk perception (Mesken et al., 2007).<br />

Cai and L<strong>in</strong> (2011) demonstrated a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> visual attention to a lead car when the participant’s<br />

arousal level was high and the experienced emotional valence was negative. As Mesken and<br />

colleagues (2007) demonstrated <strong>in</strong> a real driv<strong>in</strong>g situation, higher anger levels led to a reduction <strong>in</strong><br />

perceived risk and – as a consequence – traffic situations were <strong>in</strong>terpreted as be<strong>in</strong>g less dangerous<br />

under the <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> this emotion. In both studies (Cai & L<strong>in</strong>, 2011; Mesken et al., 2007), the<br />

participants drove faster and caused more traffic violations.<br />

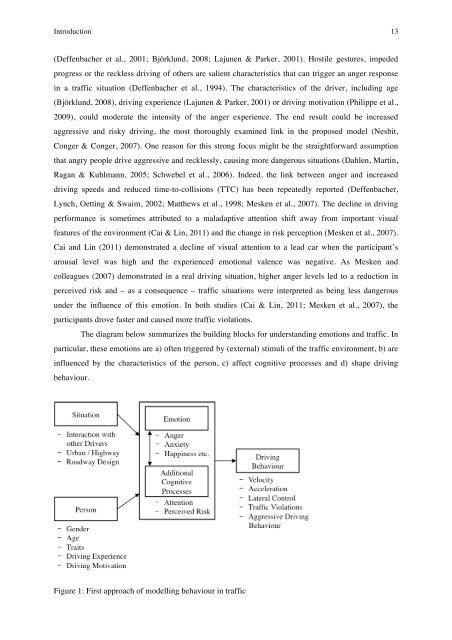

The diagram below summarizes the build<strong>in</strong>g blocks for understand<strong>in</strong>g emotions and traffic. In<br />

particular, these emotions are a) <strong>of</strong>ten triggered by (external) stimuli <strong>of</strong> the traffic environment, b) are<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenced by the characteristics <strong>of</strong> the person, c) affect cognitive processes and d) shape driv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

behaviour.<br />

Figure 1: First approach <strong>of</strong> modell<strong>in</strong>g behaviour <strong>in</strong> traffic<br />

!