Chemical & Engineering News Digital Edition ... - IMM@BUCT

Chemical & Engineering News Digital Edition ... - IMM@BUCT

Chemical & Engineering News Digital Edition ... - IMM@BUCT

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK<br />

COURTESY OF PHOENIX IPY TEAM<br />

EXTREME CHEMISTRY<br />

Chemists working in extreme environments<br />

mix SCIENCE WITH ADVENTURE<br />

LINDA WANG, C&EN WASHINGTON<br />

SHIVERING INSIDE a tent in an isolated<br />

area of Antarctica, Tufts University professor<br />

of chemistry Samuel P. Kounaves could<br />

barely feel his fingers as he tried to keep the<br />

solution in his pipette from freezing. Outside<br />

the tent, the temperature was −30 ºC.<br />

The barren, cracked land in these so-called<br />

dry valleys looked eerily like Mars.<br />

In fact, that’s the reason Kounaves and<br />

colleagues embarked on this three-week<br />

expedition in December 2007. They wanted<br />

to do a trial run of analytical instruments<br />

that would be taken to Mars by the Phoenix<br />

Lander, and these dry valleys in Antarctica<br />

are similar to some regions of the red planet.<br />

“In chemistry, you think a lot of us just<br />

want to be in the lab, but, in reality, I think<br />

a lot of chemists are extroverts and they<br />

enjoy going out into the world and doing<br />

things,” Kounaves says. “We’re explorers<br />

at heart.”<br />

Kounaves isn’t alone in seeking answers<br />

to scientific questions in such<br />

extreme environments. As chemistry<br />

becomes increasingly interdisciplinary,<br />

chemists are finding more opportunities<br />

to do fieldwork, which has traditionally<br />

been the domain of researchers in the<br />

natural sciences, in areas such as oceanography<br />

and vulcanology. In this stormy job<br />

market, the ability to work at the intersection<br />

of multiple scientific disciplines and<br />

to be imaginative about how chemistry<br />

is applied to big-picture problems could<br />

provide a safe haven.<br />

Fieldwork can take many forms, from a<br />

local half-day trip to a monthlong excursion<br />

to the other side of the world. The<br />

example of Kounaves and two other chemists<br />

working on the far end of the spectrum<br />

demonstrates that there’s no limit to what<br />

chemists can do.<br />

Tamsin A. Mather, an academic fellow<br />

in the earth sciences department at the<br />

University of Oxford, understands the<br />

trials and tribulations of doing fieldwork<br />

in extreme environments. She studies the<br />

atmospheric chemistry of volcanic plumes<br />

and their effects on the environment.<br />

Mather says that the most extreme place<br />

she’s worked in is Lascar Volcano, in the<br />

Chilean Andes. What made it so challenging<br />

for her team is the high altitude, which<br />

MORE ONLINE<br />

WWW.CEN-ONLINE.ORG 55 NOVEMBER 3, 2008<br />

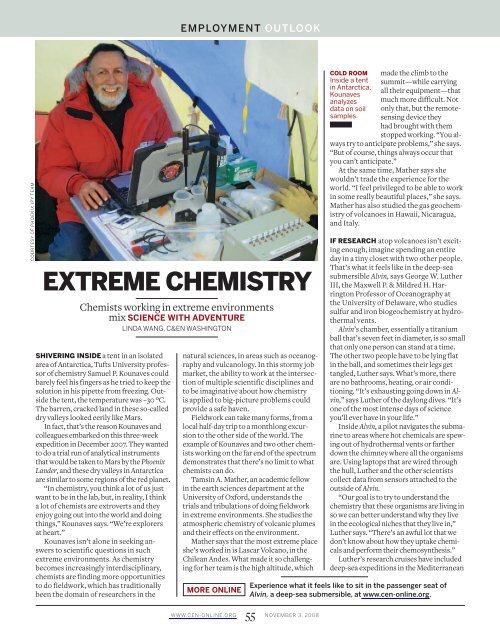

COLD ROOM<br />

Inside a tent<br />

in Antarctica,<br />

Kounaves<br />

analyzes<br />

data on soil<br />

samples.<br />

made the climb to the<br />

summit—while carrying<br />

all their equipment—that<br />

much more difficult. Not<br />

only that, but the remotesensing<br />

device they<br />

had brought with them<br />

stopped working. “You always<br />

try to anticipate problems,” she says.<br />

“But of course, things always occur that<br />

you can’t anticipate.”<br />

At the same time, Mather says she<br />

wouldn’t trade the experience for the<br />

world. “I feel privileged to be able to work<br />

in some really beautiful places,” she says.<br />

Mather has also studied the gas geochemistry<br />

of volcanoes in Hawaii, Nicaragua,<br />

and Italy.<br />

IF RESEARCH atop volcanoes isn’t exciting<br />

enough, imagine spending an entire<br />

day in a tiny closet with two other people.<br />

That’s what it feels like in the deep-sea<br />

submersible Alvin, says George W. Luther<br />

III, the Maxwell P. & Mildred H. Harrington<br />

Professor of Oceanography at<br />

the University of Delaware, who studies<br />

sulfur and iron biogeochemistry at hydrothermal<br />

vents.<br />

Alvin’s chamber, essentially a titanium<br />

ball that’s seven feet in diameter, is so small<br />

that only one person can stand at a time.<br />

The other two people have to be lying flat<br />

in the ball, and sometimes their legs get<br />

tangled, Luther says. What’s more, there<br />

are no bathrooms, heating, or air conditioning.<br />

“It’s exhausting going down in Alvin,”<br />

says Luther of the daylong dives. “It’s<br />

one of the most intense days of science<br />

you’ll ever have in your life.”<br />

Inside Alvin, a pilot navigates the submarine<br />

to areas where hot chemicals are spewing<br />

out of hydrothermal vents or farther<br />

down the chimney where all the organisms<br />

are. Using laptops that are wired through<br />

the hull, Luther and the other scientists<br />

collect data from sensors attached to the<br />

outside of Alvin.<br />

“Our goal is to try to understand the<br />

chemistry that these organisms are living in<br />

so we can better understand why they live<br />

in the ecological niches that they live in,”<br />

Luther says. “There’s an awful lot that we<br />

don’t know about how they uptake chemicals<br />

and perform their chemosynthesis.”<br />

Luther’s research cruises have included<br />

deep-sea expeditions in the Mediterranean<br />

Experience what it feels like to sit in the passenger seat of<br />

Alvin, a deep-sea submersible, at www.cen-online.org.