Edited by Rachel Duncan 4th Edition ISBN 0-907649-91-2 London ...

Edited by Rachel Duncan 4th Edition ISBN 0-907649-91-2 London ...

Edited by Rachel Duncan 4th Edition ISBN 0-907649-91-2 London ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

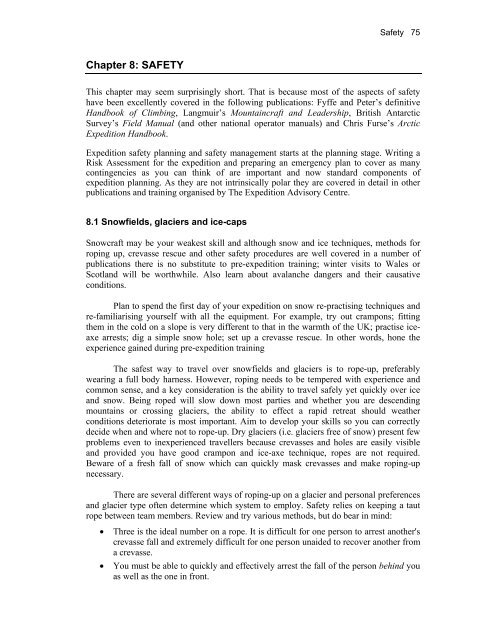

Chapter 8: SAFETY<br />

Safety 75<br />

This chapter may seem surprisingly short. That is because most of the aspects of safety<br />

have been excellently covered in the following publications: Fyffe and Peter’s definitive<br />

Handbook of Climbing, Langmuir’s Mountaincraft and Leadership, British Antarctic<br />

Survey’s Field Manual (and other national operator manuals) and Chris Furse’s Arctic<br />

Expedition Handbook.<br />

Expedition safety planning and safety management starts at the planning stage. Writing a<br />

Risk Assessment for the expedition and preparing an emergency plan to cover as many<br />

contingencies as you can think of are important and now standard components of<br />

expedition planning. As they are not intrinsically polar they are covered in detail in other<br />

publications and training organised <strong>by</strong> The Expedition Advisory Centre.<br />

8.1 Snowfields, glaciers and ice-caps<br />

Snowcraft may be your weakest skill and although snow and ice techniques, methods for<br />

roping up, crevasse rescue and other safety procedures are well covered in a number of<br />

publications there is no substitute to pre-expedition training; winter visits to Wales or<br />

Scotland will be worthwhile. Also learn about avalanche dangers and their causative<br />

conditions.<br />

Plan to spend the first day of your expedition on snow re-practising techniques and<br />

re-familiarising yourself with all the equipment. For example, try out crampons; fitting<br />

them in the cold on a slope is very different to that in the warmth of the UK; practise iceaxe<br />

arrests; dig a simple snow hole; set up a crevasse rescue. In other words, hone the<br />

experience gained during pre-expedition training<br />

The safest way to travel over snowfields and glaciers is to rope-up, preferably<br />

wearing a full body harness. However, roping needs to be tempered with experience and<br />

common sense, and a key consideration is the ability to travel safely yet quickly over ice<br />

and snow. Being roped will slow down most parties and whether you are descending<br />

mountains or crossing glaciers, the ability to effect a rapid retreat should weather<br />

conditions deteriorate is most important. Aim to develop your skills so you can correctly<br />

decide when and where not to rope-up. Dry glaciers (i.e. glaciers free of snow) present few<br />

problems even to inexperienced travellers because crevasses and holes are easily visible<br />

and provided you have good crampon and ice-axe technique, ropes are not required.<br />

Beware of a fresh fall of snow which can quickly mask crevasses and make roping-up<br />

necessary.<br />

There are several different ways of roping-up on a glacier and personal preferences<br />

and glacier type often determine which system to employ. Safety relies on keeping a taut<br />

rope between team members. Review and try various methods, but do bear in mind:<br />

• Three is the ideal number on a rope. It is difficult for one person to arrest another's<br />

crevasse fall and extremely difficult for one person unaided to recover another from<br />

a crevasse.<br />

• You must be able to quickly and effectively arrest the fall of the person behind you<br />

as well as the one in front.