- Page 1 and 2:

LOAD AND RESISTANCEFACTOR DESIGNSPE

- Page 3:

iiCopyright © 2000byAmerican Insti

- Page 6 and 7:

vTABLE OF CONTENTSSYMBOLS . . . . .

- Page 8 and 9:

TABLE OF CONTENTSviiSPECIFICATION (

- Page 10 and 11:

TABLE OF CONTENTSixSPECIFICATION (C

- Page 12 and 13:

TABLE OF CONTENTSxiCOMMENTARY (Cont

- Page 18 and 19:

SYMBOLSxviistrength (for those stee

- Page 20 and 21:

SYMBOLSxixS eff Effective section m

- Page 22 and 23:

SYMBOLSxxit s Web stiffener thickne

- Page 24 and 25:

xxiiiGLOSSARYAlignment chart for co

- Page 26 and 27:

GLOSSARYxxvEffective moment of iner

- Page 28 and 29:

GLOSSARYxxviiLateral bracing member

- Page 30 and 31:

GLOSSARYxxixPost-buckling strength.

- Page 32 and 33:

GLOSSARYxxxiStrain-hardening strain

- Page 34 and 35:

1CHAPTER AGENERAL PROVISIONSA1. SCO

- Page 36 and 37:

Sect. A3.] MATERIAL 3Cold-Formed We

- Page 38 and 39:

Sect. A3.] MATERIAL 5ASTM A449 bolt

- Page 40 and 41:

Sect. A6.] REFERENCED CODES AND STA

- Page 42 and 43:

Sect. A7.] DESIGN DOCUMENTS 9tion A

- Page 44 and 45:

Sect. B4.] STABILITY 11(a) When the

- Page 46 and 47:

Sect. B10.] PROPORTIONS OF BEAMS AN

- Page 48 and 49:

Sect. B10.] PROPORTIONS OF BEAMS AN

- Page 50 and 51:

17Chap. CCHAPTER CFRAMES AND OTHER

- Page 52 and 53:

Sect. C3.] STABILITY BRACING 19all

- Page 54 and 55:

Sect. C3.] STABILITY BRACING 214. B

- Page 56 and 57:

Sect. C3.] STABILITY BRACING 231.0;

- Page 58 and 59:

Sect. D3.] PIN-CONNECTED MEMBERS AN

- Page 60 and 61:

27Chap. ECHAPTER ECOLUMNS AND OTHER

- Page 62 and 63:

Sect. E4.] BUILT-UP MEMBERS 29(a) F

- Page 64 and 65:

31Chap. FCHAPTER FBEAMS AND OTHER F

- Page 66 and 67:

Sect. F1.] DESIGN FOR FLEXURE 33Lp=

- Page 68 and 69:

Sect. F2.] DESIGN FOR SHEAR 35Lpd

- Page 70 and 71:

37Chap. GCHAPTER GPLATE GIRDERSI-sh

- Page 72 and 73:

Sect. H3.] ALTERNATIVE INTERACTION

- Page 74 and 75:

Sect. I2.] COMPRESSION MEMBERS 41ti

- Page 76 and 77:

Sect. I3.] FLEXURAL MEMBERS 434. Lo

- Page 78 and 79:

Sect. I3.] FLEXURAL MEMBERS 45welde

- Page 80 and 81:

Sect. I5.] SHEAR CONNECTORS 47A c =

- Page 82 and 83:

49Chap. JCHAPTER JCONNECTIONS, JOIN

- Page 84 and 85:

Sect. J1.] GENERAL PROVISIONS 518.

- Page 86 and 87:

Sect. J2.] WELDS 53Welding ProcessT

- Page 88 and 89:

Sect. J2.] WELDS 55For end-loaded f

- Page 90 and 91:

Sect. J2.] WELDS 57Types of Weld an

- Page 92 and 93:

Sect. J3.] BOLTS AND THREADED PARTS

- Page 94 and 95:

Sect. J3.] BOLTS AND THREADED PARTS

- Page 96 and 97:

Sect. J3.] BOLTS AND THREADED PARTS

- Page 98 and 99:

Sect. J3.] BOLTS AND THREADED PARTS

- Page 100 and 101:

Sect. J4.] DESIGN RUPTURE STRENGTH

- Page 102 and 103:

Sect. J8.] BEARING STRENGTH 69J6. F

- Page 104 and 105:

71Chap. KCHAPTER KCONCENTRATED FORC

- Page 106 and 107:

Sect. K1.] FLANGES AND WEBS WITH CO

- Page 108 and 109:

For P u 0.4P yR v = 0.60F y d c t

- Page 110 and 111:

Sect. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADIN

- Page 112 and 113:

79Chap. LCHAPTER LSERVICEABILITY DE

- Page 114 and 115:

81Chap. MCHAPTER MFABRICATION, EREC

- Page 116 and 117:

Sect. M4.] ERECTION 83(2) Bottom su

- Page 118 and 119:

Sect. M5.] QUALITY CONTROL 85The fa

- Page 120 and 121:

Sect. N3.] EVALUATION BY STRUCTURAL

- Page 122 and 123:

89App. BAPPENDIX BDESIGN REQUIREMEN

- Page 124 and 125:

App. B5.] LOCAL BUCKLING 914kc=h/tw

- Page 126 and 127:

App. B5.] LOCAL BUCKLING 93é0.877

- Page 128 and 129:

App. E3.] DESIGN COMPRESSIVE STRENG

- Page 130 and 131:

App. F1.] DESIGN FOR FLEXURE 97For

- Page 132 and 133:

App. F1.] DESIGN FOR FLEXURE 99TABL

- Page 134 and 135:

App. F1.] DESIGN FOR FLEXURE 101Cri

- Page 136 and 137:

App. F3.] WEB-TAPERED MEMBERS 103j

- Page 138 and 139:

App. F3.] WEB-TAPERED MEMBERS 105Fw

- Page 140 and 141:

107App. GAPPENDIX GPLATE GIRDERSThi

- Page 142 and 143:

App. G3.] DESIGN SHEAR STRENGTH 109

- Page 144 and 145:

App. G5.] FLEXURE-SHEAR INTERACTION

- Page 146 and 147:

App. H3.] ALTERNATIVE INTERACTION E

- Page 148 and 149: 115App. JAPPENDIX JCONNECTIONS, JOI

- Page 150 and 151: App. J3.] BOLTS AND THREADED PARTS

- Page 152 and 153: App. K2.] PONDING 119æçMetric:lC

- Page 154 and 155: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 156 and 157: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 158 and 159: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 160 and 161: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 162 and 163: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 164 and 165: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 166 and 167: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 168 and 169: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 170 and 171: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 172 and 173: App. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADING

- Page 174 and 175: NUMERICAL VALUES 141TABLE 2ItemShap

- Page 176 and 177: NUMERICAL VALUES 143Klr123456789101

- Page 178 and 179: NUMERICAL VALUES 145TABLE 3-50Desig

- Page 180 and 181: NUMERICAL VALUES 147TABLE 4Values o

- Page 182 and 183: NUMERICAL VALUES 149TABLE 5 (cont

- Page 184 and 185: NUMERICAL VALUES 151TABLE 7Values o

- Page 186 and 187: NUMERICAL VALUES 153f vVAwnTABLE 8-

- Page 188 and 189: NUMERICAL VALUES 155f vVAwnTABLE 8-

- Page 190 and 191: NUMERICAL VALUES 157hf vVAwnTABLE 9

- Page 192 and 193: NUMERICAL VALUES 159f vVAwnTABLE 9-

- Page 194 and 195: NUMERICAL VALUES 161ht wf vVAwnTABL

- Page 196 and 197: 163COMMENTARYon the Load and Resist

- Page 200 and 201: Comm. A3.] MATERIAL 167and Chen, 19

- Page 202 and 203: Comm. A3.] MATERIAL 169than the ant

- Page 204 and 205: Comm. A4.] LOADS AND LOAD COMBINATI

- Page 206 and 207: Comm. A5.] DESIGN BASIS 173where =

- Page 208 and 209: Comm. A5.] DESIGN BASIS 175( )bsln(

- Page 210 and 211: 177Comm. BCHAPTER BDESIGN REQUIREME

- Page 212 and 213: Comm. B5.] LOCAL BUCKLING 179(c) Al

- Page 214 and 215: Comm. B5.] LOCAL BUCKLING 181load.

- Page 216 and 217: Comm. B7.] LIMITING SLENDERNESS RAT

- Page 218 and 219: Comm. C1.] SECOND ORDER EFFECTS 185

- Page 220 and 221: Comm. C1.] SECOND ORDER EFFECTS 187

- Page 222 and 223: Comm. C2.] FRAME STABILITY 189Buckl

- Page 224 and 225: Comm. C2.] FRAME STABILITY 191Notes

- Page 226 and 227: Comm. C2.] FRAME STABILITY 193Where

- Page 228 and 229: Comm. C3.] STABILITY BRACING 195age

- Page 230 and 231: Comm. C3.] STABILITY BRACING 197pla

- Page 232 and 233: Comm. C3.] STABILITY BRACING 199The

- Page 234 and 235: Comm. C3.] STABILITY BRACING 201Par

- Page 236 and 237: 203Comm. ECHAPTER ECOLUMNS AND OTHE

- Page 238 and 239: Comm. E4.] BUILT-UP MEMBERS 205TABL

- Page 240 and 241: Comm. F1.] DESIGN FOR FLEXURE 207ha

- Page 242 and 243: Comm. F1.] DESIGN FOR FLEXURE 2092b

- Page 244 and 245: Comm. F4.] BEAMS AND GIRDERS WITH W

- Page 246 and 247: Comm. H2.] UNSYMMETRIC MEMBERS AND

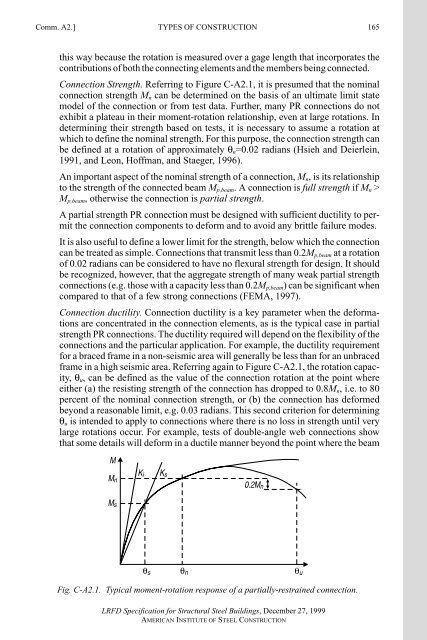

- Page 248 and 249:

Comm. I2.] COMPRESSION MEMBERS 215d

- Page 250 and 251:

Comm. I3.] FLEXURAL MEMBERS 217may

- Page 252 and 253:

Comm. I3.] FLEXURAL MEMBERS 219The

- Page 254 and 255:

Comm. I3.] FLEXURAL MEMBERS 221wher

- Page 256 and 257:

Comm. I3.] FLEXURAL MEMBERS 223proc

- Page 258 and 259:

Comm. I4.] COMBINED COMPRESSION AND

- Page 260 and 261:

Comm. I5.] SHEAR CONNECTORS 227tal

- Page 262 and 263:

229Comm. JCHAPTER JCONNECTIONS, JOI

- Page 264 and 265:

Comm. J1.] GENERAL PROVISIONS 231 P

- Page 266 and 267:

Comm. J2.] WELDS 2332b. Limitations

- Page 268 and 269:

Comm. J2.] WELDS 235When longitudin

- Page 270 and 271:

Comm. J2.] WELDS 237due to cyclic f

- Page 272 and 273:

Comm. J2.] WELDS 239(b) Plane 2-2,

- Page 274 and 275:

Comm. J3.] BOLTS AND THREADED PARTS

- Page 276 and 277:

Comm. J3.] BOLTS AND THREADED PARTS

- Page 278 and 279:

Comm. J3.] BOLTS AND THREADED PARTS

- Page 280 and 281:

Comm. J4.] DESIGN RUPTURE STRENGTH

- Page 282 and 283:

249Comm. KCHAPTER KCONCENTRATED FOR

- Page 284 and 285:

Comm. K1.] FLANGES AND WEBS WITH CO

- Page 286 and 287:

Comm. K1.] FLANGES AND WEBS WITH CO

- Page 288 and 289:

Comm. K2.] PONDING 255Even on the b

- Page 290 and 291:

257Comm. LCHAPTER LSERVICEABILITY D

- Page 292 and 293:

Comm. L5.] CORROSION 259orthotropic

- Page 294 and 295:

Comm. M4.] ERECTION 261It is sugges

- Page 296 and 297:

Comm. N4.] EVALUATION BY LOAD TESTS

- Page 298 and 299:

Comm. N5.] EVALUATION REPORT 265N5.

- Page 300 and 301:

267Comm. A-EAPPENDIX ECOLUMNS AND O

- Page 302 and 303:

Comm. App. F3.] WEB-TAPERED MEMBERS

- Page 304 and 305:

271Comm. A-GAPPENDIX GPLATE GIRDERS

- Page 306 and 307:

273Comm. A-KAPPENDIX JCONNECTIONS,

- Page 308 and 309:

Comm. J2.] WELDS 275found to be con

- Page 310 and 311:

Comm. K3.] DESIGN FOR CYCLIC LOADIN

- Page 312 and 313:

279ReferencesAckroyd, M. H., and Ge

- Page 314 and 315:

REFERENCES 281Bjorhovde, R. (1972),

- Page 316 and 317:

REFERENCES 283Fielding, D. J., and

- Page 318 and 319:

REFERENCES 285Johnson, D. L. (1985)

- Page 320 and 321:

REFERENCES 287Ollgaard, J. G., Slut

- Page 322 and 323:

REFERENCES 289Zhou, S. P., and Chen

- Page 324 and 325:

SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY 291Kotec

- Page 326 and 327:

Metric Conversion Factors for Commo