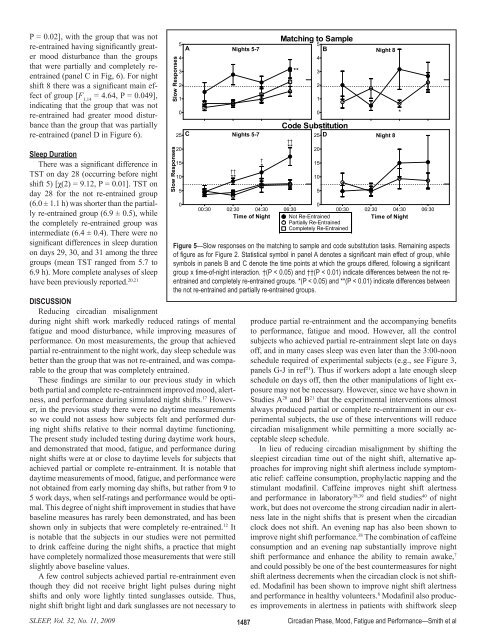

Median RT (msec)1600A140012001000800C6Slow Responses420Nights 5-7Nights 5-7Mathematical Processing****1600B140012001000800D6Night 8000:30 02:30 04:30 06:3000:30 02:30 04:30 06:30Time of Night Not Re-EntrainedTime of NightPartially Re-EntrainedCompletely Re-Entrained42Night 8*there was a significant main effect ofgroup on night shifts 5–7 [F 2,35= 4.14,P = 0.02]. The group that was not reentrainedhad significantly more slowresponses than the group that was partiallyre-entrained, but the differencebetween the not-entrained and <strong>com</strong>pletelyre-entrained groups did notreach statistical significance (P = 0.06)(panel A in Figure 5). There was a significantgroup × time-of-night interactionfor the number of slow responseson night shift 8 [F 3,39= 3.48, P = 0.04].Simple main effects showed that thesource of this interaction was significantlymore slow responses for the notre-entrained group <strong>com</strong>pared to thepartially re-entrained group during the4:30 test bout (panel B in Figure 5).Figure 4—Median reaction time (top) and slow responses (bottom) on the mathematical processing task.Remaining aspects of figure as for Fig 2. Statistical symbols in panels A, B, and C denote a significantmain effect of group. *(P < 0.05) and **(P < 0.01) indicate differences between the not re-entrained andpartially re-entrained groups.significant group × time-of-night interaction during night shifts5–7 [F 6,108= 2.87, P = 0.02]. Simple main effects indicated thatthe not re-entrained group had significantly more slow responsesthan both the partially or <strong>com</strong>pletely re-entrained groups duringthe 2:30, 4:30, and 6:30 test bouts (panel C in Figure 3).There were no significant differences between the groups onnight shift 8 (panel D in Figure 3).Code Substitution TaskThere were no group differences inmedian RT (data not shown). However,the group that was not re-entrained hadmore slow responses (Figure 5, bottomrow). There was a significant group × time-of-night interactionon nights 5–7 [F 6,108= 2.78, P = 0.02]. The not re-entrainedgroup had significantly more slow responses than both the partiallyre-entrained and <strong>com</strong>pletely re-entrained groups duringthe 2:30, 4:30, and 6:30 test bouts (panel C in Figure 5). Therewere no significant group differences in the number of slowresponses on night shift 8 (panel D in Figure 5).Mathematical Processing TaskPerformance was better than during baseline for all 3 groups,but the partially and <strong>com</strong>pletely re-entrained group performedbetter than the not re-entrained group. Median RT was slowerin the not re-entrained group (Figure 4, top row). There wasa significant main effect of group during nights 5–7 [F 2,34=5.65, P < 0.01]. Post hoc tests indicated that the not re-entrainedgroup had significantly slower median RT than the partially reentrainedgroup (panel A in Figure 4). On night shift 8 there wasalso a significant main effect of group [F 1,12= 7.79, P = 0.02],indicating that the group that was not re-entrained had significantlyslower reaction times than the partially re-entrainedgroup (panel B in Figure 4).The number of slow responses was greater for subjects thatdid not achieve re-entrainment (Figure 4, bottom row). Onnights 5–7 there was a significant main effect of group [F 2,35= 8.25, P < 0.01]. The not re-entrained group had significantlymore slow responses than the partially re-entrained group (panelC in Figure 4). Slow responses on night shift 8 showed a similarpattern, but the main effect of group did not achieve statisticalsignificance [F 1,13= 3.92, P = 0.07] (panel D in Figure 4).Matching to Sample TaskMedian RT was close to baseline levels throughout thenight shifts, and there were no significant differences amongthe groups (data not shown). For the number of slow responsesMental Fatigue and Mood DisturbanceAll the groups began the night shifts with ratings of mentalfatigue and total mood disturbance that were relatively closeto their baseline levels (00:30 time points in Figure 6). Duringnight shifts 5–7 (Figure 6, left panels), mental fatigue and totalmood disturbance increased for all groups later in the nightshifts, but the partially and <strong>com</strong>pletely re-entrained groups remainedcloser to their baseline ratings late in the nights, whilethe group that was not re-entrained became more fatigued andhad greater mood disturbance. On night shift 8 (Figure 6, rightpanels), ratings for the partially re-entrained group remainedvery close to baseline levels, while the not re-entrained groupdemonstrated increased mental fatigue and mood disturbance,especially later in the night shift.On the mental fatigue scale for nights 5–7, there was a significantmain effect of group [F 2,36= 5.48, P < 0.01]. Post hoctests indicated that the not re-entrained group was significantlymore mentally fatigued than the partially and <strong>com</strong>pletely re-entrainedgroups (panel A in Figure 6). During night shift 8 therewas a main effect of group [F 1,14= 4.84, P = 0.045], indicatingthat the group that was not re-entrained was more mentallyfatigued than the group that achieved partial re-entrainment(panel B in Figure 6).Total mood disturbance was also higher for the group thatwas not re-entrained (Figure 6, bottom row). On night shifts5–7, there was a significant main effect of group [F 2,36= 4.12,SLEEP, Vol. 32, No. 11, 2009 1486Circadian Phase, Mood, Fatigue and Performance—Smith et al

P = 0.02], with the group that was notre-entrained having significantly greatermood disturbance than the groupsthat were partially and <strong>com</strong>pletely reentrained(panel C in Fig, 6). For nightshift 8 there was a significant main effectof group [F 1,14= 4.64, P = 0.049],indicating that the group that was notre-entrained had greater mood disturbancethan the group that was partiallyre-entrained (panel D in Figure 6).Sleep DurationThere was a significant difference inTST on day 28 (occurring before nightshift 5) [χ(2) = 9.12, P = 0.01]. TST onday 28 for the not re-entrained group(6.0 ± 1.1 h) was shorter than the partiallyre-entrained group (6.9 ± 0.5), whilethe <strong>com</strong>pletely re-entrained group wasintermediate (6.4 ± 0.4). There were nosignificant differences in sleep durationon days 29, 30, and 31 among the threegroups (mean TST ranged from 5.7 to6.9 h). More <strong>com</strong>plete analyses of sleephave been previously reported. 20,215ADISCUSSIONReducing circadian misalignmentduring night shift work markedly reduced ratings of mentalfatigue and mood disturbance, while improving measures ofperformance. On most measurements, the group that achievedpartial re-entrainment to the night work, day sleep schedule wasbetter than the group that was not re-entrained, and was <strong>com</strong>parableto the group that was <strong>com</strong>pletely entrained.These findings are similar to our previous study in whichboth partial and <strong>com</strong>plete re-entrainment improved mood, alertness,and performance during simulated night shifts. 17 However,in the previous study there were no daytime measurementsso we could not assess how subjects felt and performed duringnight shifts relative to their normal daytime functioning.The present study included testing during daytime work hours,and demonstrated that mood, fatigue, and performance duringnight shifts were at or close to daytime levels for subjects thatachieved partial or <strong>com</strong>plete re-entrainment. It is notable thatdaytime measurements of mood, fatigue, and performance werenot obtained from early morning day shifts, but rather from 9 to5 work days, when self-ratings and performance would be optimal.This degree of night shift improvement in studies that havebaseline measures has rarely been demonstrated, and has beenshown only in subjects that were <strong>com</strong>pletely re-entrained. 12 Itis notable that the subjects in our studies were not permittedto drink caffeine during the night shifts, a practice that mighthave <strong>com</strong>pletely normalized those measurements that were stillslightly above baseline values.A few control subjects achieved partial re-entrainment eventhough they did not receive bright light pulses during nightshifts and only wore lightly tinted sunglasses outside. Thus,night shift bright light and dark sunglasses are not necessary toSlow ResponsesSlow Responses43210Nights 5-725 CNights 5-720151050††**†*Matching to Sample**5BCode Substitution††**43210Night 825 DNight 8201510000:30 02:30 04:30 06:3000:30 02:30 04:30 06:30Time of Night Not Re-EntrainedTime of NightPartially Re-EntrainedCompletely Re-EntrainedFigure 5—Slow responses on the matching to sample and code substitution tasks. Remaining aspectsof figure as for Figure 2. Statistical symbol in panel A denotes a significant main effect of group, whilesymbols in panels B and C denote the time points at which the groups differed, following a significantgroup x time-of-night interaction. †(P < 0.05) and ††(P < 0.01) indicate differences between the not reentrainedand <strong>com</strong>pletely re-entrained groups. *(P < 0.05) and **(P < 0.01) indicate differences betweenthe not re-entrained and partially re-entrained groups.5produce partial re-entrainment and the ac<strong>com</strong>panying benefitsto performance, fatigue and mood. However, all the controlsubjects who achieved partial re-entrainment slept late on daysoff, and in many cases sleep was even later than the 3:00-noonschedule required of experimental subjects (e.g., see Figure 3,panels G-J in ref 21 ). Thus if workers adopt a late enough sleepschedule on days off, then the other manipulations of light exposuremay not be necessary. However, since we have shown inStudies A 20 and B 21 that the experimental interventions almostalways produced partial or <strong>com</strong>plete re-entrainment in our experimentalsubjects, the use of these interventions will reducecircadian misalignment while permitting a more socially acceptablesleep schedule.In lieu of reducing circadian misalignment by shifting thesleepiest circadian time out of the night shift, alternative approachesfor improving night shift alertness include symptomaticrelief: caffeine consumption, prophylactic napping and thestimulant modafinil. Caffeine improves night shift alertnessand performance in laboratory 38,39 and field studies 40 of nightwork, but does not over<strong>com</strong>e the strong circadian nadir in alertnesslate in the night shifts that is present when the circadianclock does not shift. An evening nap has also been shown toimprove night shift performance. 38 The <strong>com</strong>bination of caffeineconsumption and an evening nap substantially improve nightshift performance and enhance the ability to remain awake, 7and could possibly be one of the best countermeasures for nightshift alertness decrements when the circadian clock is not shifted.Modafinil has been shown to improve night shift alertnessand performance in healthy volunteers. 8 Modafinil also producesimprovements in alertness in patients with shiftwork sleep*SLEEP, Vol. 32, No. 11, 2009 1487Circadian Phase, Mood, Fatigue and Performance—Smith et al

- Page 1 and 2:

Practice Management Tips ForSHIFT W

- Page 3 and 4:

Patient QuestionnaireDo you often f

- Page 5 and 6:

Sleep/Wake LogIn bedOut of bedLight

- Page 7 and 8:

PHQ-9 QUICK DEPRESSION ASSESSMENTFo

- Page 9 and 10:

Insomnia Severity IndexPlease answe

- Page 11 and 12:

Take-Away PointsSHIFT WORK DISORDER

- Page 13 and 14:

SHIFT WORKDISORDERBright Light Ther

- Page 40 and 41:

PrimarycareScreeningfor depressioni

- Page 42 and 43:

PrimarycareThescreening questionnai

- Page 44 and 45:

Shift-work disorderContents and Fac

- Page 46 and 47:

Shift-work disorderThe diagnosis of

- Page 48 and 49:

Shift-work disorderas heightened le

- Page 50 and 51:

Shift-work disorderFigure 1 Risk ra

- Page 52 and 53:

Shift-work disorderare not function

- Page 54 and 55:

The characterization andpathology o

- Page 56 and 57:

Shift-work disorderFigure 2 Sleep/w

- Page 58 and 59:

Shift-work disorderFigure 3 Blood p

- Page 60 and 61:

Recognition of shift-workdisorder i

- Page 62 and 63:

Shift-work disorderThe timing of sh

- Page 64 and 65:

Shift-work disorderthe other potent

- Page 66 and 67:

Managing the patient withshift-work

- Page 68 and 69:

Shift-work disorderFigure 3 Optimal

- Page 70 and 71:

Shift-work disorderfor a motor vehi

- Page 72 and 73:

Shift-work disordermoderate caffein

- Page 74 and 75:

Supplement toAvailable at jfponline

- Page 76 and 77:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 78 and 79:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 80 and 81:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 82 and 83:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 84 and 85:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 86 and 87:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 88 and 89:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 90 and 91:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 92 and 93:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 94 and 95:

Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 96 and 97: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 98 and 99: The Epidemiology and Diagnosis of I

- Page 100 and 101: The Epidemiology and Diagnosis of I

- Page 102 and 103: The Epidemiology and Diagnosis of I

- Page 120 and 121: CIRCADIAN RHYTHM SLEEP DISORDERSPra

- Page 122 and 123: Table 2— AASM Levels of Recommend

- Page 124 and 125: 3.2.1.1 Both the Morningness-Evenin

- Page 126 and 127: Five studies used one of the newer

- Page 128 and 129: as an indicator of phase in sighted

- Page 130 and 131: 4.4 Advanced Sleep Phase DisorderBe

- Page 132 and 133: 45. Walsh, JK, Randazzo, AC, Stone,

- Page 134: 123. Van Someren, EJ, Kessler, A, M

- Page 142 and 143: Table 1—Subject Demographicsn M:F

- Page 144 and 145: Scale. 28 The simple reaction time

- Page 148 and 149: 10Mentally AExhaustedSharpScore8642

- Page 150 and 151: Current Treatment Options in Neurol

- Page 152 and 153: 398 Sleep Disordersand sleep loss,

- Page 154 and 155: 400 Sleep DisordersTable 1. Treatme

- Page 156 and 157: 402 Sleep DisordersStandard dosageC

- Page 158 and 159: 404 Sleep DisordersStandard procedu

- Page 160 and 161: 406 Sleep DisordersCaffeineMelatoni

- Page 162 and 163: 408 Sleep DisordersWake-promoting a

- Page 164 and 165: 410 Sleep Disordersnight shift: ada