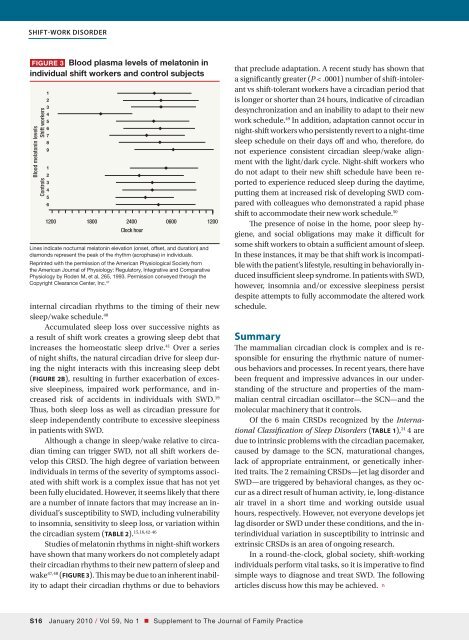

Shift-work disorderFigure 3 Blood plasma levels of melatonin inindividual shift workers and control subjectsBlood melatonin levelsShift workersControls1234567891234561200 1800 2400 0600 1200Clock hourLines indicate nocturnal melatonin elevation (onset, offset, and duration) anddiamonds represent the peak of the rhythm (acrophase) in individuals.Reprinted with the permission of the American Physiological Society fromthe American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and ComparativePhysiology by Roden M, et al, 265, 1993. Permission conveyed through theCopyright Clearance Center, Inc. 47internal circadian rhythms to the timing of their newsleep/wake schedule. 40Accumulated sleep loss over successive nights asa result of shift work creates a growing sleep debt thatincreases the homeostatic sleep drive. 41 Over a seriesof night shifts, the natural circadian drive for sleep duringthe night interacts with this increasing sleep debt(FIGURE 2B), resulting in further exacerbation of excessivesleepiness, impaired work performance, and increasedrisk of accidents in individuals with SWD. 19Thus, both sleep loss as well as circadian pressure forsleep independently contribute to excessive sleepinessin patients with SWD.Although a change in sleep/wake relative to circadiantiming can trigger SWD, not all shift workers developthis CRSD. The high degree of variation betweenindividuals in terms of the severity of symptoms associatedwith shift work is a <strong>com</strong>plex issue that has not yetbeen fully elucidated. However, it seems likely that thereare a number of innate factors that may increase an individual’ssusceptibility to SWD, including vulnerabilityto insomnia, sensitivity to sleep loss, or variation withinthe circadian system (TABLE 2). 15,16,42-46Studies of melatonin rhythms in night-shift workershave shown that many workers do not <strong>com</strong>pletely adapttheir circadian rhythms to their new pattern of sleep andwake 47,48 (FIGURE 3). This may be due to an inherent inabilityto adapt their circadian rhythms or due to behaviorsthat preclude adaptation. A recent study has shown thata significantly greater (P < .0001) number of shift-intolerantvs shift-tolerant workers have a circadian period thatis longer or shorter than 24 hours, indicative of circadiandesynchronization and an inability to adapt to their newwork schedule. 49 In addition, adaptation cannot occur innight-shift workers who persistently revert to a night-timesleep schedule on their days off and who, therefore, donot experience consistent circadian sleep/wake alignmentwith the light/dark cycle. Night-shift workers whodo not adapt to their new shift schedule have been reportedto experience reduced sleep during the daytime,putting them at increased risk of developing SWD <strong>com</strong>paredwith colleagues who demonstrated a rapid phaseshift to ac<strong>com</strong>modate their new work schedule. 50The presence of noise in the home, poor sleep hygiene,and social obligations may make it difficult forsome shift workers to obtain a sufficient amount of sleep.In these instances, it may be that shift work is in<strong>com</strong>patiblewith the patient’s lifestyle, resulting in behaviorally inducedinsufficient sleep syndrome. In patients with SWD,however, insomnia and/or excessive sleepiness persistdespite attempts to fully ac<strong>com</strong>modate the altered workschedule.SummaryThe mammalian circadian clock is <strong>com</strong>plex and is responsiblefor ensuring the rhythmic nature of numerousbehaviors and processes. In recent years, there havebeen frequent and impressive advances in our understandingof the structure and properties of the mammaliancentral circadian oscillator—the SCN—and themolecular machinery that it controls.Of the 6 main CRSDs recognized by the InternationalClassification of Sleep Disorders (TABLE 1), 21 4 aredue to intrinsic problems with the circadian pacemaker,caused by damage to the SCN, maturational changes,lack of appropriate entrainment, or genetically inheritedtraits. The 2 remaining CRSDs—jet lag disorder andSWD—are triggered by behavioral changes, as they occuras a direct result of human activity, ie, long-distanceair travel in a short time and working outside usualhours, respectively. However, not everyone develops jetlag disorder or SWD under these conditions, and the interindividualvariation in susceptibility to intrinsic andextrinsic CRSDs is an area of ongoing research.In a round-the-clock, global society, shift-workingindividuals perform vital tasks, so it is imperative to findsimple ways to diagnose and treat SWD. The followingarticles discuss how this may be achieved. nS16 January 2010 / Vol 59, No 1 • Supplement to The Journal of Family Practice

References1. Moore RY. Circadian rhythms: basic neurobiologyand clinical applications. Annu Rev Med.1997;48:253-266.2. Czeisler CA, Klerman EB. Circadian and sleepdependentregulation of hormone release in humans.Recent Prog Horm Res. 1999;54:97-130.3. Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, et al. Stability,precision, and near-24-hour period of thehuman circadian pacemaker. Science. 1999;248:2177-2181.4. Eskin A. Identification and physiology of circadianpacemakers. Fed Proc. 1979;38:2570-2572.5. Berson DM, Dunn FA, Takao M. Phototransductionby retinal ganglion cells that set the circadianclock. Science. 2002;295:1070-1073.6. Hattar S, Liao HW, Takao M, et al. Melanopsincontainingretinal ganglion cells: architecture,projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science.2002;295:1065-1070.7. Lincoln GA, Ebling FJ, Almeida OF. Generationof melatonin rhythms. Ciba Found Symp.1985;117:129-148.8. Reppert SM, Perlow MJ, Ungerleider LG, et al.Effects of damage to the suprachiasmatic areaof the anterior hypothalamus on the daily melatoninand cortisol rhythms in rhesus monkeys.J Neurosci. 1981;1:1414-1425.9. Edwards S, Evans P, Hucklebridge F, et al. Associationbetween time of awakening and diurnalcortisol secretory activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology.2001;26:613-622.10. Gillette MU, Reppert SM. The hypothalamic suprachiasmaticnuclei: circadian patterns of vasopressinsecretion and neuronal activity in vitro.Brain Res Bull. 1987;19:135-139.11. Maywood ES, Reddy AB, Wong GK, et al. Synchronizationand maintenance of timekeepingin suprachiasmatic circadian clock cells byneuropeptidergic signaling. Curr Biol. 2006;16:599-605.12. Schwartz WJ, Gainer H. Suprachiasmatic nucleus:use of 14 C-labeled deoxyglucose uptake as afunctional marker. Science. 1977;197;1089-1091.13. Yamazaki S, Kerbeshian MC, Hocker CG, et al.Rhythmic properties of the hamster suprachiasmaticnucleus in vivo. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10709-10723.14. DeCoursey PJ, Krulas JR. Behavior of SCNlesionedchipmunks in natural habitat: a pilotstudy. J Biol Rhythms. 1998;13:229-244.15. Carpen JD, Archer SN, Skene DJ, et al. A singlenucleotidepolymorphism in the 5′-untranslatedregion of the hPER2 gene is associated with diurnalpreference. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:293-297.16. Katzenberg D, Young T, Finn L, et al. A CLOCKpolymorphism associated with human diurnalpreference. Sleep. 1998;21:569-576.17. Borbély AA, Achermann P. Concepts and modelsof sleep regulation: an overview. J Sleep Res.1992;1:63-79.18. Borbély AA, Achermann P, Trachsel L, et al. Sleepinitiation and initial sleep intensity: interactionsof homeostatic and circadian mechanisms. J BiolRhythms. 1989;4:149-160.19. Akerstedt T. Sleepiness as a consequence of shiftwork. Sleep. 1988;11:17-34.20. Penev PD, Kolker DE, Zee PC, et al. Chronic circadiandesynchronization decreases the survivalof animals with cardiomyopathic heart disease.Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H2334-H2337.21. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. InternationalClassification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnosticand Coding Manual. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL:American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.22. Toh KL. Basic science review on circadianrhythm biology and circadian sleep disorders.Ann Acad Singapore. 2008;37:662-668.23. Dagan Y, Eisenstein M. Circadian rhythm sleepdisorders: toward a more precise definition anddiagnosis. Chronobiol Int. 1999;16:213-222.24. Ando K, Kripke DF, Ancoli-Israel S. Delayed andadvanced sleep phase syndromes. Isr J PsychiatryRelat Sci. 2002;39:11-18.25. Sack RL, Lewy AJ, Blood ML, et al. Circadianrhythm abnormalities in totally blind people:incidence and clinical significance. J Clin EndocrinolMetab. 1992;75:127-134.26. Ebisawa T. Circadian rhythms in the CNS andperipheral clock disorders: human sleep disordersand clock genes. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;103:150-154.27. Ebisawa T, Uchiyama M, Kajimura N, et al. Associationof structural polymorphisms in thehuman period3 gene with delayed sleep phasesyndrome. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:342-346.28. Pereira DS, Tufik S, Louzada FM, et al. Associationof the length polymorphism in the humanPer3 gene with the delayed sleep phase syndrome:does latitude have an influence on it?Sleep. 2005;28:29-32.29. Aoki H, Ozeki Y, Yamada N. Hypersensitivity ofmelatonin suppression in response to light inpatients with delayed sleep phase syndrome.Chronobiol Int. 2001;18:263-271.30. Sack RL, Auckley D, Auger RR, et al. Circadianrhythm sleep disorders: part II, advanced sleepphase disorder, delayed sleep phase disorder,free-running disorder, and irregular sleep-wakerhythm. An American Academy of Sleep MedicineReview. Sleep. 2007;30:1484-1501.31. Jones CR, Campbell SS, Zone SE, et al. Familialadvanced sleep-phase syndrome: a short-periodcircadian rhythm variant in humans. Nat Med.1999;5:1062-1065.32. Toh KL, Jones CR, He Y, et al. An hPer2 phosphorylationsite mutation in familial advanced sleepphase syndrome. Science. 2001;291:1040-1043.33. Vaneslow K, Vaneslow JT, Westermark PO, etal. Differential effects of PER2 phosphorylation:molecular basis for the human familialadvanced sleep phase syndrome (FASPS). GenesDev. 2006;20:2660-2672.34. Xu Y, Padiath QS, Shapiro RE, et al. Functionalconsequences of a CKIδ mutation causing familialadvanced sleep phase syndrome. Nature.2005;434:640-644.35. Sack RL, Lewy AJ. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders:lessons from the blind. Sleep Med Rev.2001;5:189-206.36. Comperatore CA, Krueger GP. Circadian rhythmdesynchronosis, jet lag, shift lag, and copingstrategies. Occup Med. 1990;5:323-341.37. Sack RL, Auckley D, Auger RR, et al. Circadianrhythmsleep disorders: part I, basic principles,shift work and jet lag disorders. Sleep. 2007;30:1460-1483.38. Waterhouse J, Reilly T, Atkinson G, et al. Jet lag:trends and coping strategies. Lancet. 2007;369:1117-1129.39. Drake CL, Roehrs T, Richardson G, et al. Shiftwork sleep disorder: prevalence and consequencesbeyond that of symptomatic day workers.Sleep. 2004;27:1453-1462.40. Smith MR, Fogg LF, Eastman CI. Practical interventionsto promote circadian adaptation to permanentnight shift work: study 4. J Biol Rhythms.2009;24:161-172.41. Park YM, Matsumoto PK, Seo YJ, et al. Sleep-wakebehavior of shift workers using wrist actigraph.Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54:359-360.42. Drake C, Richardson G, Roehrs T, et al. Vulnerabilityto stress-related sleep disturbance andhyperarousal. Sleep. 2004;27:285-291.43. Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Situational insomnia:consistency, predictors, and out<strong>com</strong>es. Sleep.2003;26:1029-1036.44. Watson NF, Goldberg J, Arguelles L, et al. Geneticand environmental influences on insomnia,daytime sleepiness, and obesity in twins. Sleep.2006;29:645-649.45. Viola AU, Archer SN, James LM, et al. PER3 polymorphismpredicts sleep structure and wakingperformance. Curr Biol. 2007;17:613-618.46. James FO, Cermakian N, Boivin DB. Circadianrhythms of melatonin, cortisol, and clock geneexpression during simulated night shift work.Sleep. 2007;30:1427-1436.47. Roden M, Koller M, Pirich K, et al. The circadianmelatonin and cortisol secretion pattern in permanentnight shift workers. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R261-R267.48. Sack RL, Blood ML, Lewy AJ. Melatonin rhythmsin night shift workers. Sleep. 1992;15:434-441.49. Reinberg A, Ashkenazi I. Internal desynchronizationof circadian rhythms and tolerance to shiftwork. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25:625-643.50. Quera-Salva MA, Defrance R, Claustrat B, et al.Rapid shift in sleep time and acrophase of melatoninsecretion in short shift work schedule.Sleep. 1996;19:539-543.Supplement to The Journal of Family Practice • Vol 59, No 1 / January 2010 S17

- Page 1 and 2:

Practice Management Tips ForSHIFT W

- Page 3 and 4:

Patient QuestionnaireDo you often f

- Page 5 and 6:

Sleep/Wake LogIn bedOut of bedLight

- Page 7 and 8: PHQ-9 QUICK DEPRESSION ASSESSMENTFo

- Page 9 and 10: Insomnia Severity IndexPlease answe

- Page 11 and 12: Take-Away PointsSHIFT WORK DISORDER

- Page 13 and 14: SHIFT WORKDISORDERBright Light Ther

- Page 40 and 41: PrimarycareScreeningfor depressioni

- Page 42 and 43: PrimarycareThescreening questionnai

- Page 44 and 45: Shift-work disorderContents and Fac

- Page 46 and 47: Shift-work disorderThe diagnosis of

- Page 48 and 49: Shift-work disorderas heightened le

- Page 50 and 51: Shift-work disorderFigure 1 Risk ra

- Page 52 and 53: Shift-work disorderare not function

- Page 54 and 55: The characterization andpathology o

- Page 56 and 57: Shift-work disorderFigure 2 Sleep/w

- Page 60 and 61: Recognition of shift-workdisorder i

- Page 62 and 63: Shift-work disorderThe timing of sh

- Page 64 and 65: Shift-work disorderthe other potent

- Page 66 and 67: Managing the patient withshift-work

- Page 68 and 69: Shift-work disorderFigure 3 Optimal

- Page 70 and 71: Shift-work disorderfor a motor vehi

- Page 72 and 73: Shift-work disordermoderate caffein

- Page 74 and 75: Supplement toAvailable at jfponline

- Page 76 and 77: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 78 and 79: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 80 and 81: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 82 and 83: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 84 and 85: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 86 and 87: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 88 and 89: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 90 and 91: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 92 and 93: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 94 and 95: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 96 and 97: Armodafinil for Treatment of Excess

- Page 98 and 99: The Epidemiology and Diagnosis of I

- Page 100 and 101: The Epidemiology and Diagnosis of I

- Page 102 and 103: The Epidemiology and Diagnosis of I

- Page 120 and 121:

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM SLEEP DISORDERSPra

- Page 122 and 123:

Table 2— AASM Levels of Recommend

- Page 124 and 125:

3.2.1.1 Both the Morningness-Evenin

- Page 126 and 127:

Five studies used one of the newer

- Page 128 and 129:

as an indicator of phase in sighted

- Page 130 and 131:

4.4 Advanced Sleep Phase DisorderBe

- Page 132 and 133:

45. Walsh, JK, Randazzo, AC, Stone,

- Page 134:

123. Van Someren, EJ, Kessler, A, M

- Page 142 and 143:

Table 1—Subject Demographicsn M:F

- Page 144 and 145:

Scale. 28 The simple reaction time

- Page 146 and 147:

Median RT (msec)1600A14001200100080

- Page 148 and 149:

10Mentally AExhaustedSharpScore8642

- Page 150 and 151:

Current Treatment Options in Neurol

- Page 152 and 153:

398 Sleep Disordersand sleep loss,

- Page 154 and 155:

400 Sleep DisordersTable 1. Treatme

- Page 156 and 157:

402 Sleep DisordersStandard dosageC

- Page 158 and 159:

404 Sleep DisordersStandard procedu

- Page 160 and 161:

406 Sleep DisordersCaffeineMelatoni

- Page 162 and 163:

408 Sleep DisordersWake-promoting a

- Page 164 and 165:

410 Sleep Disordersnight shift: ada