Olive Senior - PEN International

Olive Senior - PEN International

Olive Senior - PEN International

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

WORDS ... ABOUT <strong>PEN</strong> INTERNATIONAL<br />

About <strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

Published biannually, <strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong> presents the work of contemporary writers from<br />

around the world in English, French and Spanish. Founded in 1950, it was relaunched in<br />

2007 with the express goal of introducing the work of new and established writers to each<br />

other and to readers everywhere. Contributors have included Adonis, Margaret Atwood,<br />

Nawal El Saadawi, Nadine Gordimer, Günter Grass, Han Suyin, Chenjerai Hove, Alberto<br />

Manguel, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Moniro Ravanipour, Salman Rushdie, Wole Soyinka and<br />

many others. <strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong> is the magazine of the worldwide writers’ association,<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>PEN</strong>. For more information about our work, and for submission guidelines<br />

to the magazine, visit www.internationalpen.org.uk.<br />

À propos de <strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

Le magazine <strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong> paraît deux fois par an. Il présente des œuvres d’écrivains<br />

contemporains du monde entier, en anglais, en français et en espagnol. Fondé en 1950, il<br />

a été relancé en 2007 avec pour but exprès de présenter les œuvres d’écrivains débutants<br />

aux écrivains établis, et vice versa, ainsi qu’aux lecteurs du monde entier. Il a recueilli la<br />

contribution d’Adonis, de Margaret Atwood, de Nawal El Saadawi, de Nadine Gordimer, de<br />

Günter Grass, de Han Suyin, de Chenjerai Hove, d’Alberto Manguel, de Ngugi wa Thiong’o,<br />

de Moniro Ravanipour, de Salman Rushdie, de Wole Soyinka et de nombre d’autres. <strong>PEN</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong> est le magazine de l’association internationale d’écrivains, <strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong>.<br />

Pour plus d’informations sur notre travail, et pour prendre connaissance des conditions de<br />

soumission de contributions au magazine, rendez-vous sur www.internationalpen.org.uk.<br />

Acerca de <strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong> es una publicación semestral que presenta el trabajo de escritores<br />

contemporáneos de todo el mundo en inglés, francés y español. Esta publicación nació<br />

en 1950 y ha sido relanzada en 2007 con el objetivo de presentar el trabajo de escritores<br />

reconocidos y noveles a otros escritores y lectores de todo el mundo. Hasta ahora hemos<br />

recibido aportaciones de Adonis, Margaret Atwood, Nawal El Saadawi, Nadine Gordimer,<br />

Günter Grass, Han Suyin, Chenjerai Hove, Alberto Manguel, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Moniro<br />

Ravanipour, Salman Rushdie y Wole Soyinka, entre otros. <strong>PEN</strong> <strong>International</strong> es la revista<br />

de la asociación internacional de escritores, <strong>PEN</strong> Internacional. Para obtener más<br />

información sobre nuestro trabajo y sobre cómo hacer aportaciones a la revista,<br />

visite www.internationalpen.org.uk.

2<br />

WORDS ... CONTENTS<br />

Contents<br />

4 EDITOR’S NOTE<br />

5 COMMEMORATION:<br />

WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE 50TH ANNIVERSARY<br />

Ed Sowerby 1971: Nguyên Chí Thiên<br />

6 POÈMES DE PROSE<br />

Sylvestre Clancier Histoire de fouilles / Histoires de fous / Histoires<br />

de maux / Histoires de mots<br />

9 POEM<br />

Sujata Bhatt Truth Is Mute<br />

11 CONMEMORACIÓN:<br />

COMITÉ DE ESCRITORES EN PRISIÓN: 50.º ANIVERSARIO<br />

Jamie Jauncey 1972: Xosé Luís Méndez Ferrín<br />

12 STORY<br />

Pauline Melville Is This Platform Four, Madam? Is It?<br />

16 ESSAI<br />

Patrice Nganang La Mort de la littérature francophone<br />

20 POEM<br />

<strong>Olive</strong> <strong>Senior</strong> Her Granddaughter Learns the Alphabet<br />

21 EXTRACTO<br />

Donato Ndongo-Bidyogo Los Hijos de la tribu<br />

26 STORY<br />

Esther Heboyan Picture Bride<br />

33 COMMEMORATION:<br />

WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE 50TH : Nguyên Chí Thiên<br />

ANNIVERSARY<br />

Tamara O’Brien 1986: Adam Michnik<br />

34 BLOOMBERG FOUND IN TRANSLATION / DÉCOUVERT<br />

EN TRADUCTION / DESCUBIERTO EN TRADUCCIÓN<br />

CONTE<br />

S. Y. Agnon Les Bougies<br />

Traduit de l’hébreu par Rita Sabah<br />

EXTRACTO<br />

Susana Medina Juguetes filosóficos<br />

Traducido del inglés por la autora<br />

POEMA<br />

Victor Terán Luna<br />

Traducido del zapoteco por el autor<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

40 COMMEMORATION:<br />

WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE 50 TH ANNIVERSARY<br />

Matt Turner 1990: Aung San Suu Kyi<br />

41 EXCERPT<br />

Casey Merkin The Crimes of Paris<br />

45 CUENTA<br />

Sara Caba Le Temo<br />

47 POEM<br />

Anzhelina Polonskaya Two Birds<br />

POÈME<br />

Larissa Miller Intitulée<br />

48 GRAPHIC ESSAY<br />

Amruta Patil Seated Scribe<br />

50 COMMEMORATION:<br />

WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE 50 TH ANNIVERSARY<br />

Nick Parker 1997: Faraj Sarkoohi<br />

51 POÈME<br />

Abdelmajid Benjelloun Les Yeux de Pessoa<br />

52 POEM<br />

John Mateer Pessanha’s House, Lisbon<br />

53 RECOLLECTION<br />

Walerian Domanski Smoke Factories<br />

57 CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Back cover:<br />

COMMEMORATION:<br />

WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE 50 TH ANNIVERSARY<br />

Elise Valmorbida 2010: the Unknown Writer<br />

WORDS ... CONTENTS<br />

3<br />

Musine Kokalari 1960

4<br />

WORDS ... EDITOR’S NOTE<br />

Editor’s Note<br />

TROILUS: Words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart:<br />

The effect doth operate another way.<br />

Troilus and Cressida, Act V, Sc. III<br />

Welcome to the 2010 spring/summer issue, which shares its theme with <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>PEN</strong>’s Free the Word! festivals in Linz, Austria (October 2009) and London (April 2010),<br />

playing on Troilus’s cynical dismissal of his errant lover’s letter in Shakespeare’s<br />

tragedy. Free the Word! London gathered dozens of writers from as many countries,<br />

and here we present works by many festival participants including Sujata Bhatt,<br />

James Kelman, John Mateer, Pauline Melville, Donato Ndongo-Bidyogo, Amruta Patil,<br />

Nawal El Saadawi, <strong>Olive</strong> <strong>Senior</strong> and Michela Wrong. The festival’s inaugural event,<br />

a discussion about the re-shaping of English to express different cultural identities,<br />

is transcribed on page 71.<br />

Elsewhere, Kelman gives us the music of Glaswegian Scots through a conflicted<br />

pub-goer; one of Melville’s mysterious Gypsies obsesses over his final destination;<br />

Patil reflects on the proliferation of ‘scribes’; <strong>Senior</strong> experiences language as legacy;<br />

Walerian Domanski recalls a Stalinist fiction made policy; Lucio Lami remembers a<br />

haunting cry from a war zone; Susana Medina’s sculptress discovers el placer complejo<br />

del lenguaje; Patrice Nganang pronounces francophone literature ‘dead’; Rafik Schami<br />

chronicles the history of Arabic script; and Christopher L. Silzer learns his true name.<br />

This issue also commemorates fifty years of <strong>International</strong> <strong>PEN</strong>’s Writers in Prison<br />

Committee (WiPC), which has campaigned tirelessly on behalf of endangered<br />

minds, voices and words the world over. <strong>International</strong> <strong>PEN</strong> and the WiPC have<br />

launched ‘Because Writers Speak Their Minds’, a yearlong campaign of anniversary<br />

events, writing, petitions, special projects, case studies and much more (visit<br />

www.internationalpen.org.uk for details).<br />

Marking the occasion in these pages, we present six poems from 26:50, a creative<br />

collaboration between the WiPC and the writers’ association 26, conceived in<br />

conjunction with the WiPC’s own selection of fifty emblematic cases to illustrate the<br />

sad continuum of oppression as well as happy instances of reinstatement in cultural<br />

life.<br />

Words, words, nothing but … words? Indeed. Nothing but words, and the whole of life<br />

expressed though them: we hope you enjoy this issue, dedicated to the possibilities<br />

and limitations of language, and to the men and women shut up for exploring them.<br />

Mitchell Albert, Editor<br />

mitchell.albert@internationalpen.org.uk<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

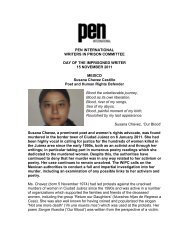

WORDS ... WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE 50TH ANNIVERSARY<br />

WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE 50 TH ANNIVERSARY<br />

Ed Sowerby<br />

1971: Nguyên Chí Thiên<br />

It took me eight minutes to learn fifty words by heart last night.<br />

You didn’t remember fifty, you remembered five hundred.<br />

And not words, whole poems. Paperless poems.<br />

Stories from the Steel Trap.<br />

Forty years later it’s others who memorise them.<br />

Shows it’s not the ink that makes a writer.<br />

Poet Nguyên Chí Thiên . was detained repeatedly by the Vietnamese<br />

authorities for his writings and for ‘spreading propaganda’.<br />

He spent a total of twenty-seven years in prison, and was released<br />

in 1991. He lives in the US. See: ‘Because Writers Speak Their Minds’,<br />

the fiftieth-anniversary campaign of <strong>International</strong> <strong>PEN</strong>’s Writers in<br />

Prison Committee; www.internationalpen.org.uk and http://26-<br />

50.tumblr.com.<br />

5<br />

WiPC<br />

50

6<br />

DES PAROLES ... SYLVESTRE CLANCIER<br />

Sylvestre Clancier<br />

Histoire de fouilles / Histoires<br />

de fous / Histoires de maux /<br />

Histoires de mots<br />

I. Ethnologie<br />

Il avait une verrue banale au bout du pied, à chaque pas pesant<br />

des racines de Kwayanupik écorchaient sa verrue ; n’en pouvant<br />

plus, il demanda à son porteur Kornu de la tribu des Tarézons de<br />

lui faire un pansement. Ce dernier lui dit de s’asseoir au pied<br />

d’un grand Kanayou (lat : Quercus rosandus) et de l’attendre là.<br />

Quelques instants plus tard, le porteur revint en compagnie<br />

de deux guerriers de la tribu des Phrypouyes qui tenaient dans<br />

leurs bras des herbes Katayules (hypotheticae) des tiges de<br />

«Saxhos» (instrumenti musicae), des cheveux d’hommes dingos<br />

(delirio trementes) et des écailles de Krokos (reptili magni).<br />

L’un des guerriers s’adressa à notre héros en ces termes :<br />

« Ya – veve – rhuorhi, /yin – halo – boudhu, /dwa – acha –<br />

Kemhou, /wen – hanyeme – fezebo, /bhonan – pou – vhanpu,<br />

/yedemenh – daha – mopa, /pakre – pudelhatri, /bhude – tatre,<br />

/thordem – pherinbend, /dhaj – dhouye, /konetha – pehne –<br />

yeta, /porth – inpend, /zemanh. »<br />

Hélas, le porteur Kornu de la tribu des Tarézons ne connaissait<br />

pas la langue Phrypouye.<br />

Notre héros se mit à pleurer, les deux guerriers s’enfuirent en<br />

criant.<br />

II. Géologie<br />

« Ferrugineux est le métal, diamantaire est le charbon » se dit un<br />

jour, saisi d’une illumination soudaine, Narcisse Bougie. « Mais<br />

alors, allons-y, devenons riches ! » s’écria-t-il.<br />

Sans même s’en douter, il renouvela sur-champ une expérience<br />

historique. Tel Bernard Palissy il jeta ses meubles au feu, dans un<br />

but cependant différent puisqu’à vrai dire il n’en avait pas : sa<br />

seule motivation étant la certitude de s’enrichir.<br />

Il commanda ensuite un amas de charbon, il choisit<br />

l’anthracite pour son haut degré de parenté avec le diamant.<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

DES PAROLES ... SYLVESTRE CLANCIER<br />

Il le fit entreposer dans sa maison, n’épargnant qu’un étroit réduit<br />

d’où, se nourrissant de pain et d’eau, il pourrait le contempler à loisir.<br />

Il savait que la recherche de l’or en pierre, à partir de certains<br />

principes philosophales, avait en vain préoccupé avant lui bon nombre<br />

d’honnêtes gens ; mais, sachant que le diamant était incomparable,<br />

il n’avait pas la moindre idée d’échec.<br />

Ses connaissances géologiques lui disaient qu’en plusieurs<br />

millénaires le charbon se changeait en diamant. Aussi, frénétiquement<br />

enthousiaste, il se mit à observer jour et nuit la lente évolution de<br />

son stock. Armé d’une loupe, il inspectait avec minutie les moindres<br />

fissures de chacun des boulets dans l’espoir d’y déceler un éclat plus<br />

intense.<br />

Son espoir était si ardent qu’il ne vit point le temps passer : le poids<br />

des ans ne pesa point sur ses épaules.<br />

Un matin, ou plutôt on ne sait quand, ses yeux se firent diamants :<br />

le charbon resplendissait. Il ouvrit sa fenêtre : le monde n’existait plus.<br />

Il faisait froid, une immense épaisseur de glace entourait sa maison.<br />

Il ne put enflammer ses diamants, et mourut bien avant qu’ils ne<br />

redeviennent charbons ardents.<br />

III. Métallurgie<br />

Les galeries s’emplissent du bruit de ses pas, les portes claquent, les<br />

murs résonnent et renvoient sa voix. Oui, Mr Peter Schönhold a la<br />

vulgaire manie d’inspecter tous les jours sa maison de retraite.<br />

Sous ses pieds crissent des graviers d’argent et vole une poussière<br />

d’or. En effet, Mr Peter, roi de l’acier suédois, eut l’idée voici quelques<br />

années de parer sa demeure de divers métaux rares. Un jour, il aime<br />

surveiller son jardinier taillant quelques haies de cobalt ; un autre, il<br />

ordonne à ses gens d’orner de pommes d’or ses compotiers d’ivoire,<br />

puis il s’en va allègrement pousser sa tondeuse chimique sur son gazon<br />

d’airain. Mais aujourd’hui, après une courte promenade, Mr Peter s’en<br />

va s’asseoir sur son fauteuil cuivré. De là, il s’attarde à contempler la<br />

massive statue d’argent allégorie du Temps qu’il a fait ériger au nom<br />

de la devise.<br />

Par la porte restée entrellée, notre roi de l’acier perçoit soudain<br />

des voix. Prêtant l’oreille, il entend de méchantes paroles :<br />

« Le Schönhold, c’est une vraie tête de bois.<br />

– Oui, c’est même un vrai cœur de pierre.<br />

– Tu as raison, et nos malheurs ne sont pas près de finir, car le<br />

bonhomme a une santé de fer. »<br />

Alors, le roi de l’acier suédois se tord de douleur sur son fauteuil<br />

cuivré.<br />

Toute une vie perdue : il s’en rend compte maintenant. Que lui<br />

7

8<br />

DES PAROLES ... SYLVESTRE CLANCIER<br />

importe que le Temps soit de l’argent, puisqu’il lui faut apprendre de<br />

la bouche de ses gens que lui-même, pauvre être misérable à la santé<br />

de fer, n’est rien qu’une tête de bois et un vrai cœur de pierre.<br />

Il s’est levé, est allé au jardin pour congédier son jardinier et lui donner<br />

ses pommes d’or. Puis il est rentré, a fermé ses volets et, se fiant au<br />

conseil de ses gens, est allé se coucher. Ainsi, ayant en peu de temps<br />

perdu son argent, sa tête de bois, son cœur de pierre, Mr Schönhold a<br />

sans plus attendre mis au clou sa santé de fer : on l’a trouvé mort le<br />

lendemain. Son modeste enterrement s’est passé sans histoire ; le jour<br />

suivant, Schönhold, le roi de l’acier, était oublié.<br />

Aujourd’hui, si lors d’un voyage en Suède, on fait un détour par la<br />

ville de Hockmarhaüsen, on peut voir dans un coin du cimetière une<br />

tombe abandonnée sur laquelle sont gravés ces mots :<br />

« Ci-gît Mr Peter Schönhold<br />

Il avait un cœur d’or. »<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

Sujata Bhatt<br />

Truth Is Mute<br />

Truth is mute, she says,<br />

but you need words to find it.<br />

A bull’s head in water, a mermaid’s split tail –<br />

centuries in silt, and the words that came down to us:<br />

a blue spell of longing, now translucent on paper.<br />

Is filigrane the sound you want<br />

or is it watermark?<br />

How many dictionaries<br />

do you need for the words you seek?<br />

Remember, she says,<br />

instinct is wordless<br />

even as it lives within words.<br />

Remember, she says,<br />

love will be silent with love.<br />

Mother tongue, father tongue –<br />

when the child started to speak<br />

she used all her words at once,<br />

at once in a rush: pani, water, Wasser.<br />

When the child started to speak<br />

she meant fish and Fisch.<br />

How many languages must you learn<br />

before you can understand your own?<br />

When she lived on a mountain<br />

amongst people whose language<br />

WORDS ... SUJATA BHATT 9

10<br />

WORDS ... SUJATA BHATT<br />

she did not know, her own language turned<br />

into a festival of fruits, and a festival of birds.<br />

When she lived on a mountain<br />

oxygen-deprived, near ice-covered rocks,<br />

she only dreamt of the sea<br />

night after night – algae and seaweed.<br />

Will oxygen determine the meaning of your words?<br />

Remember, she says,<br />

love will be silent with salt.<br />

Remember, she says,<br />

truth is mute, and love will be silent.<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

PALABRAS ... COMITÉ DE ESCRITORES EN PRISIÓN: 50. o ANIVERSARIO<br />

COMITÉ DE ESCRITORES EN PRISIÓN: 50. o ANIVERSARIO<br />

Jamie Jauncey<br />

1972: Xosé Luís Méndez Ferrín<br />

El general y tú<br />

compartíais un derecho<br />

Ese torpe bastardo<br />

boca llena de astillas<br />

la lengua maternal<br />

Mas cuando le puso<br />

su bota encima<br />

olvidó que los clavos<br />

en el régimen de prisión<br />

afilan la Resistencia<br />

aguzan el desprecio<br />

Mientras que la verdad<br />

como la saliva o la sangre<br />

se abre camino<br />

cuando hasta las lenguas están atadas<br />

Traducido del inglés por Franco Pesce<br />

Poeta, novelista, ensayista y profesor, Xosé Luís Méndez Ferrín<br />

estuvo en prisión bajo los regímenes de Franco y Suárez, en España,<br />

por la producción de ‘propaganda’ y por su actividad política.<br />

Fue liberado en 1980 y hoy vive y trabaja en España. Véase: ‘Porque<br />

los escritores dicen lo que piensan’, la campaña del quincuagésimo<br />

aniversario del Comité de Escritores en Prisión de <strong>PEN</strong> Internacional;<br />

www.internationalpen.org.uk, y también http://26-50.tumblr.com.<br />

11<br />

WiPC<br />

50

12<br />

WORDS ... PAULINE MELVILLE<br />

Pauline Melville<br />

Is This Platform Four, Madam?<br />

Is It?<br />

The taller of the two men was clearly agitated. He was in his twenties with a pale,<br />

oval face and dark glasses. His light stone-coloured mackintosh flared out slightly<br />

as he turned on his heel this way and that. Next to him stood a man wearing a<br />

light tweed jacket who might have been his father. The two men waited together<br />

on the concourse of Newcastle station. The station had recently been modernised.<br />

In an attempt to leave the Victorian era behind and enter the modern world it had<br />

been painted in bright nursery colours. Blue scaffolding enclosed the kiosks. Red<br />

tubular railings ran along the pedestrian bridge linking the other platforms.<br />

But the huge black overarching iron structures that supported the roof echoed<br />

the cat’s cradle of iron bridges over the Tyne and managed to hold the station in<br />

the grip of the city’s industrial past, open to the gritty airiness and invigorating<br />

breezes of the north. The older man’s white hair blew about in unruly wisps. There<br />

was something bucolic about him. He was portly, red-faced and moustachioed.<br />

The tweed jacket gave him the appearance of an English country squire. His<br />

feet were planted apart firmly on the ground. It was clear by his faint swaying<br />

backwards and forwards that he had been drinking. Beyond him a glinting skein<br />

of railway lines stretched away into the distance.<br />

The station was full of early evening summer light. Passengers had started to<br />

gather in anticipation of the London train. The younger of the two men approached<br />

a middle-aged woman who was sitting on a bench with her brown bag pinioned<br />

between her feet.<br />

‘Is this platform four, madam? Is it? Is it?’<br />

There was a hint of menace in the polite insistence of his questioning.<br />

The woman looked up to check the sign on the platform. The sign, directly<br />

overhead, said PLATFORM 4 in large letters.<br />

‘Yes. This is platform four.’<br />

‘Are you sure?’ He hovered in front of her, shifting from one foot to the other.<br />

‘Yes.’ She pointed to the sign.<br />

‘Good,’ he said. Without looking to where she was pointing, he turned away<br />

again. To the woman’s obvious surprise, she saw him approach someone else on<br />

the platform.<br />

‘Excuse me, sir, is this platform four?’ He asked the same question of the smartly<br />

dressed business man who stood nearby. Having reassured himself that this was<br />

indeed platform four, he returned to stand by the older man.<br />

The older man, oblivious to the comings and goings of his companion, readjusted<br />

his stance, once more setting his feet apart in the manner of a landlubber<br />

trying to catch his balance at sea He swayed forwards, corrected himself against<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

the pull of gravity, found the upright position, placed one hand on his chest and<br />

began to sing. His voice was light and melodious:<br />

In summertime when flow’rs do spring<br />

and birds sit on each tree,<br />

let lords and knights say what they will,<br />

there’s none so merry as we.<br />

WORDS ... PAULINE MELVILLE 13<br />

Other waiting passengers looked away. The songster seemed to have stepped out<br />

of a different period of history. When he had finished singing he looked around and<br />

said, in a melancholy tone, to no one in particular:<br />

‘Have you been to Milton Keynes? There’s nothing there.’ He paused. ‘Nothing<br />

there,’ he repeated, and heaved a great sigh, staring into the middle distance.<br />

The son, in contrast to the father’s relaxed manner, appeared precise, fastidious and<br />

nervous. There was something mocking in the expression on his pale face as he<br />

looked around the station. He waited for a minute or two before accosting another<br />

passerby:<br />

‘Excuse me, sir. Is the next train going to Doncaster? Is it the six-forty-five? Is it?’<br />

The passerby glanced at his watch and nodded. There was no mistaking the relief<br />

and intense satisfaction on the young man’s face as he acknowledged the gestured<br />

response: ‘It is. Good.’<br />

After a while the train that had been waiting in the distance began to snake its<br />

way slowly along to platform four. The woman on the bench stood up. Passengers<br />

drifted towards the edge of the platform. The young man turned and saw the<br />

approaching train, which caused a fluster of movement on his part, first toward the<br />

train; but then he swung suddenly away, and addressed a girl with spiky Mohican<br />

hair who was trying to fold up a buggy and at the same time keep an eye on her<br />

toddler:<br />

‘Is this the train going to Doncaster?’<br />

What had seemed from far away to be a toy metamorphosed into a huge<br />

train with buffet cars and dining cars gliding slowly towards them, rumbling and<br />

creaking as it came to a halt.<br />

‘Yes. This is it.’ She smiled and indicated the departures board, which stated<br />

clearly that the London train left at six-forty-five from platform four and would<br />

stop at Doncaster. ‘Look, see up there.’ But the young man was already quickening<br />

his pace to a loping run as he made his way back to his father.<br />

‘This is it. Quick,’ he said to his father with some urgency. ‘Everyone has said<br />

that this is it. They all say so. I have made several checks. The word is out that this is<br />

the right train.’ The father took his time ambling down the platform, a can of lager<br />

grasped in his hand. The son walked next to him, casting sharp anxious glances<br />

into the empty carriages. Hobbling behind them came the middle-aged woman<br />

whom the son had first addressed on the bench.<br />

The two men boarded the train and made their way down the centre aisle.<br />

They settled down opposite each other across one of the Formica-topped tables in<br />

the bleakly lit compartment. The woman was following them. She struggled to lift<br />

her bag into the overhead rack, then sat down heavily across the gangway from the<br />

pair. A handful of other passengers occupied the surrounding seats. The son could

14<br />

WORDS ... PAULINE MELVILLE<br />

not resist turning to ask one of them:<br />

‘Is this platform four?’ He received an affirmative grunt. The father scrunched<br />

up his empty can of lager, stuffed it down the side of his seat and pulled another<br />

can from his pocket, opening it with a fizzing spurt. As the train set off the younger<br />

man leaned towards the woman across the aisle:<br />

‘What time does the train reach Doncaster?’ he asked.<br />

‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘But it’s after York.’<br />

‘After York?’ He sounded suspicious. His forehead wrinkled into a frown.<br />

The dark glasses looked at her with blank threats.<br />

‘Yes. Doncaster is after York,’ she added with a friendly smile.<br />

‘After York? Are you sure? Is it? Is it? I get confused. I’d hate to be wrong.’<br />

He suddenly seemed struck with heart-rending anxiety.<br />

‘We’re Gypsies.’ The older man leaned towards the woman, addressing her<br />

with an expansive air of intimacy and wreathing her with beer fumes: ‘We’re<br />

going to Doncaster. There’ll be plenty of Gypsies there tonight. The king is buried<br />

there. With his cat.’ He gazed down at the plain tabletop and shook his head with<br />

concern:<br />

‘Although the cat hops out sometimes.’ He looked up at her again with mischief<br />

in his eyes. ‘Yes. We’re on the Donny. We’re on the Donny tonight. We’ve come from<br />

Edinburgh. Bathgate. There will be plenty of us at the gathering tonight, coming<br />

from all over the country. We’ll pour ale on the grave. And have a big party. A great<br />

shindig. That is what we do.’<br />

The son was sitting up straight and staring ahead. The seat back caused a tuft<br />

of his hair to stand up on the back of his head.<br />

‘Yes.’ The older man rubbed his hands together with relish. ‘We’ll have a good<br />

time tonight. Everyone will be in Doncaster tonight. It’ll be cushty.’<br />

The train plunged into a tunnel with a screaming hoot, and the lights in the<br />

compartment dimmed. He leaned forward:<br />

‘It’ll be cushty. Cushty.’<br />

The woman’s interest was aroused. She was left with the impression that<br />

travellers were making their way from all over the country through the dark night<br />

on their way to this secret gathering in Doncaster. Suddenly she wanted to join<br />

them.<br />

‘Where will you stay?’ she asked, curious.<br />

The father’s reply was immediately evasive. ‘Oh I dunno. In a pub, perhaps.<br />

Someone will put us up. We will stay somewhere. That’s for certain.’<br />

‘We will not be staying nowhere,’ added the son in a tone that sounded oddly<br />

supercilious. Suddenly he leaned towards her and announced in a confidential<br />

undertone:<br />

‘I’m going to marry and settle down one day.’<br />

‘How many children will you have?’ she asked, smiling.<br />

‘One or two – if the wife will let me.’ He slumped back suddenly into his seat<br />

and looked wistful as he stared out the window at the darkening landscape.<br />

The red-faced father gazed ahead in a bucolic haze and took another sip of lager.<br />

He addressed his remarks to the whole carriage:<br />

‘My wife is buried in Lincolnshire. On the way back we shall make a detour to<br />

Newton by Toft. That is near Market Rasen. Her name was Rosemarie. I want to put<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

WORDS ... PAULINE MELVILLE<br />

flowers on her grave. Hollyhocks, I think. She liked those. And lupins. Ah, now there<br />

it is beautiful. There is nothing in Milton Keynes.’ He started to sing a song about<br />

the River Afton in a tuneful voice as the train rumbled along. Then he stumbled<br />

over the words of the song, whistled for a bit, took a swig of lager from his can and<br />

picked up the thread:<br />

‘Oh, wild whistling blackbirds …’<br />

He lapsed into silence, moving from side to side with the motion of the train.<br />

Outside the night grew dark. The lighted train moved through the countryside.<br />

The train stopped at York station which caused a flurry of questions from the<br />

young man to ensure that it was not Doncaster. As the train set off again people<br />

returned from the buffet car, clutching polystyrene boxes of food as they tried to<br />

retain their balance and slopping hot coffees from plastic cartons. The carriage<br />

filled with the aroma of lukewarm chips.<br />

The train pulled into Doncaster.<br />

‘This is Doncaster, I think,’ said the woman, cupping her hand over her eyes<br />

and resting her forehead against the window as she tried to see out into the<br />

darkness. The name of the station was flashing past. ‘Can you see the signs?’<br />

she asked. ‘The train is pulling in too fast for me to read them properly.’<br />

‘We don’t read signs, madam,’ said the son haughtily as he looked around him<br />

for someone else to ask whether or not the train had arrived in Doncaster.<br />

‘We don’t read at all. We can’t read,’ added his father sagely and with<br />

satisfaction, as though they were the wiser for it. ‘It was offered to us, but we<br />

turned it down.’ He whistled a soft tune under his breath as he got up from his<br />

seat. ‘We don’t need to read words while we’ve got tongues in our throats. All those<br />

squiggles and marks that are supposed to be words. We don’t need them. We can<br />

listen. We have tongues. We hold things in our heads. And besides, we have our<br />

own signs.’ He put his finger to the side of his nose and winked.<br />

The son turned to the woman in the seat behind him:<br />

‘Is this Doncaster, madam? Are you sure? Is it? It is. Good.’<br />

15

16<br />

DES PAROLES ... PATRICE NGANANG<br />

Patrice Nganang<br />

La mort de la littérature<br />

francophone<br />

La tragédie des peuples dominés est qu’ils doivent en des intervalles réguliers<br />

répéter les étapes de leur domination. Cette répétition c’est l’histoire de leur<br />

littérature quand celle-ci est inféodée à leur histoire politique: ainsi une génération<br />

qui aux cris de « retour aux sources! » découvre les valeurs de son moi racial est<br />

succédée par une autre qui, elle, se dissout dans l’universel en une aventure où<br />

chacun tragiquement croit avoir raison. A ce même moment s’entend le cri de<br />

‘retour aux sources!’ d’une nouvelle génération qui elle aussi croit innover en<br />

remplaçant race par nation, et qui va être dépassée par une autre qui découvre<br />

soudain les limbes du cosmopolitisme. Comme si ceux-là qui ne juraient que par<br />

la race n’étaient pas des cosmopolites! Tragique est cette aventure, pas seulement<br />

à cause du piétinement de l’esprit qu’elle comporte, mais surtout à cause du<br />

circulus vitiosus dans lequel elle enferme l’intelligence de nombreuses générations.<br />

L’histoire de la littérature africaine d’expression française est marquée au signe de<br />

cette cyclique répétition, écrite qu’elle est sous ce double leitmotiv, d’abord racial<br />

et puis national, qui l’un comme l’autre ouvrent sur leur propre sabordement. Le<br />

premier leitmotiv, son histoire est d’accord là-dessus, invente en 1939 le mot pour<br />

se désigner dans le Cahier d’un retour au pays natal d’Aimé Césaire, la négritude, en<br />

plein cœur de l’expérience coloniale et au début d’une mortelle guerre mondiale,<br />

et découvre son espace d’expression en 1948 dans l’Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie<br />

nègre et malgache publiée par Léopold Sédar Senghor. L’Anthologie était une œuvre<br />

de circonstance, qui réunissait surtout des intellectuels francophones basés à Paris,<br />

on le sait ; mais elle était aussi une volonté d’inscription des mots de ces écrivains<br />

africains dans l’histoire générale des peuples noirs, un enracinement donc, 1848<br />

étant la date de l’abolition de l’esclavage dans l’espace français. « Schoelcher<br />

s’élevait avec fougue », tels sont d’ailleurs les premiers mots de ce livre devenu<br />

classique, « contre le préjugé qui attribuait aux noirs une ‘incapacité cérébrale’<br />

et proclamait ‘que la prétendue pauvreté intellectuelle des nègres est une erreur<br />

crée, entretenue, perpétrée par l’esclavage. » Victor Schoelcher, cet abolitionniste<br />

à qui Aimé Césaire consacrera bientôt un livre. Dire qu’il s’agissait de la prise de<br />

parole de l’affranchi, c’est souligner une évidence; mais croire qu’ainsi la littérature<br />

arrachait un peuple au paradigme de sa domination, c’est dire un leurre dont les<br />

écrivains d’Afrique ne sont pas encore sortis.<br />

S’il est inutile donc de signaler que Senghor, Césaire et Damas, le masculin<br />

triumvirat de la négritude, avait conscience de commencer l’histoire intellectuelle<br />

africaine contemporaine sur un nouveau pied; et c’est-à-dire surtout de cirer les<br />

chaussures de ce pied-là au noir, l’histoire de la littérature des peuples d’Afrique<br />

nous a enseigné entretemps, elle, que dans les sifflotements de leur entrain<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

DES PAROLES ... PATRICE NGANANG<br />

poétique, ils répétaient l’écho d’une voix qui avait été entendue au début du siècle,<br />

au cœur de l’Amérique de la Negro Renaissance. L’anthologie-maitresse d’Alain<br />

Locke, The New Negro : Voices of the Harlem Renaissance publiée en 1925, le lieu où<br />

cette voix s’était trouvé son élan, réunissait cette génération d’Africains-Américains<br />

qui dans les sources de la race voulaient trouver l’origine de leur chant. La clôture<br />

du grand cri enfermé entre les pages de l’anthologie de Locke aura lieu avec Ralph<br />

Ellison, l’auteur de Invisible Man, et chantre de l’intégration, qu’il formula d’ailleurs<br />

clairement dans son « Haverford Statement », en plein cœur des révoltes de 1969,<br />

quand la jeunesse noire animée par ce qu’elle appelait « nationalisme » l’appelait<br />

« sell-out », c’est-à-dire « vendu » : « j’insisterai sur mon affirmation personnelle de<br />

l’intégration sans perte de notre identité unique en tant que peuple comme étant<br />

le but possible, en fait inévitable des américains noirs », leur répondra-t-il. Si donc<br />

la négritude fait écho à la Harlem Renaissance, et d’ailleurs Senghor a toujours<br />

insisté sur cette généalogie transatlantique, la découverte par le poète-président de<br />

la « Civilisation de l’Universel », du « rendez-vous du donner et du recevoir » comme<br />

étant son achèvement nécessaire, ne peut que faire écho à cette vision clôturante<br />

d’Ellison. Il faut peut-être lire les dernières pages de l’essai-mitraillette de James<br />

Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, pour voir l’explosif que cette communauté par-delà les<br />

races représentait pour une Amérique couchée dans le lit hirsute du racisme.<br />

C’est pourtant dans les pages même de l’Anthologie de Senghor, en une<br />

introduction bien historique celle-là, « Orphée noir », que Jean-Paul Sartre aura<br />

défini l’achèvement de l’idée de la négritude comme logique, et pronostiqué<br />

sa clôture comme sabordement. ‘En fait’, écrit-il dans des lignes qu’aura le plus<br />

souligné Frantz Fanon, son lecteur assidu, « la négritude apparaît comme le temps<br />

faible d’une progression dialectique … Ce moment négatif n’a pas de suffisance<br />

en lui-même… Il vise à préparer la synthèse ou réalisation de l’humain dans<br />

une société sans races. Ainsi elle est pour se détruire, elle est passage et non<br />

aboutissement, moyen et non fin dernière. » Frantz Fanon précise, dans Peau<br />

noire, masques blancs, publié en 1952 : « Jean-Paul Sartre, dans cette étude a détruit<br />

l’enthousiasme noir »; et il continue perspicace, car il a compris que c’était l’acte de<br />

décès du mouvement qui était écrit ici avec son introduction : « l’erreur de Sartre a<br />

été non seulement de vouloir aller à la source de la source, mais en quelque sorte<br />

de tarir la source. » Pourtant ce qu’il n’aurait peut-être pas soupçonné, Fanon,<br />

c’est que « l’erreur de Sartre » sera très vite celle de Senghor, car dans l’évolution<br />

de son histoire, avec la « Civilisation de l’Universel », la négritude senghorienne<br />

écrira son propre sabordement, comme pour encore mieux donner raison à son<br />

bienfaiteur critique et préfacier parisien de 1948 ! Ah, n’est-ce pas là, dirait-on,<br />

déjà une répétition de cette histoire qui dans la littérature africaine-américaine<br />

avec Ralph Ellison avait clôt jadis les promesses racialisantes de la Harlem<br />

Renaissance ? Si seulement avec la fin de la négritude, le cercle qui limite la parole<br />

africaine dominée était ici enfin voué aux archives des idées ? Que non ! Il faudra<br />

qu’il se trouve aussi des tentacules caribéennes pour, dans le dépassement de la<br />

négritude cesairienne par cette autre trinité masculine, Chamoiseau, Bernabé<br />

et Confiant, découvrir également dans le flamboyant tombeau de la creolité sa<br />

suicidaire épiphanie ! Ainsi donc, comme possédée dans ses trois manifestations<br />

par la dictée d’une identique pulsion ontologique, la littérature des peuples noirs<br />

a-t-elle toujours trouvé, ici et là, des États-Unis aux Antilles et en Afrique, son<br />

17

18<br />

DES PAROLES ... PATRICE NGANANG<br />

anéantissement au bout d’une évolution par tout logique qui la fait tragiquement<br />

déboucher dans la béatitude universelle de son émiettement.<br />

Comme s’il n’y avait de mort digne que lorsqu’elle ne se vit pas une, mais<br />

deux, mais trois fois, le second leitmotiv de la littérature africaine d’expression<br />

française n’échappera pas à la logique répétitive de son histoire encerclée dans le<br />

paradigme de la domination. Or ici, c’est Frantz Fanon qui définira sa parturition<br />

dans les sources des projets nationaux africains de 1960. La critique de la littérature<br />

africaine ne s’est pas encore vraiment éloignée de la répartition dans Les Damnés<br />

de la terre en trois phases, des textes produits par les écrivains du continent :<br />

d’abord la littérature assimilationniste, née sous le parapluie de la condition<br />

coloniale ; ensuite le réveil à la race dont la jouvence abreuve l’écrivain au point<br />

de le constiper ; et puis enfin, plus importante pour Fanon, la littérature nationale,<br />

fruit d’une conscience bâtie au fourneau de la nation au matin de sa naissance. Fi<br />

de la race dans ce projet national des idées africaines, oui, mais c’est pour découvrir<br />

dans la nation l’origine de la littérature nouvelle, et continuer l’inféodation de<br />

la chose littéraire sous le projet politique, même si différent, celui-là ! Ils sont<br />

nombreux les auteurs qui figurent dans ce canon de la littéraire derechef enracinée<br />

dans la politique, qui au Congo avec Tchikaya U’Tamsi, au Sénégal avec Mariama<br />

Ba ou Boubacar Boris Biop, au Cameroun avec les derniers romans de Mongo Beti,<br />

ont écrit cela que sont les nations en réalité : des fictions. Or dans leur dos voici<br />

recommencer le parcours qu’on sait déjà, d’une littérature qui à peine née, de<br />

manière effiévrée court déjà vers son propre sabordement heureux! Ici avouons-le<br />

le chemin est autre, même si les étapes sont presque calquées sur le leitmotiv qui<br />

à la négritude avait déjà dicté son suicide. Les pages les plus illisibles aujourd’hui<br />

de Les Damnés de la terre, sont sans doute celles dans lesquelles Fanon argumente<br />

avec peine contre l’idéologie de la bourgeoisie néocoloniale, idéologie qui pour lui<br />

a une désignation bien claire : le cosmopolitisme. Pour Fanon le cosmopolitisme<br />

n’est pas seulement économique, donc dépendance par rapport à la métropole ;<br />

dans une tradition bien marxiste qui lui préférait l’internationalisme, il est avant<br />

tout idéologique : sa littérature est assimilationniste. Au lieu du cosmopolitisme<br />

c’est donc plutôt l’internationalisme qui fera l’auteur martiniquais embrasser la<br />

cause algérienne à rebours du triangle infâme qui a inscrit dans l’Atlantique les<br />

racines de la diaspora noire, car le cosmopolitisme voilà pour lui bien l’ordure à<br />

jeter ! C’est au nationalisme qu’il offre au contraire un futur, et par extension, au<br />

panafricanisme qui selon lui le conclut.<br />

Certes nous écrivons aujourd’hui au chevet du projet identitaire : plus que<br />

le sabordement senghorien, le génocide qui eut lieu au Rwanda en 1994 en a<br />

marqué la plus cinglante conclusion. Nous écrivons à l’extérieur du parapluie des<br />

États : l’émigration ininterrompue des auteurs africains et même l’implosion de<br />

certains États tel la Somalie ou le Soudan auront été suffisants pour nous dire<br />

combien nos pays sont mortels. Pourtant surtout c’est au milieu des ruines du<br />

projet national qui porta l’indépendance de bien d’États africains que s’installe<br />

la racine de nos mots. Voilà les conditions qui suffiraient pour expliquer le retour<br />

en force aujourd’hui du cosmopolitisme. S’il est difficile de trouver amusant cela<br />

qui faisait rire un Mongo Beti quand il écoutait le sud-africain Lewis Nkosi se<br />

présenter au congrès des écrivains africains de Berlin en 1977 comme étant un «<br />

Africain anglo-saxon », c’est sans doute parce que nous vivons bien dans une autre<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

DES PAROLES ... PATRICE NGANANG<br />

époque, nous. « Nous somme orphelins de nations », disait Sami Tchak ; des beasts<br />

of no nation, lui répond le titre d’un roman récent d’Iweala. Même les malheurs si<br />

chantés jadis de l’écrivain en exil ont perdu de leurs lustres, l’exil comme concept<br />

n’étant plus entendu lui aussi que comme un autre chapitre du projet national.<br />

Des « migrants », dit-on plutôt aujourd’hui, ou alors des « nomades » – nous<br />

sommes des écrivains « accessoirement africains », selon la formule de Waberi.<br />

Cosmopolitanism d’Anthony Appiah peut tracer dans la Grèce antique la généalogie<br />

des actes communs posés dans le marché de Koumassi, actes qui sous un regard<br />

entrainé à la lecture fanonienne, et qui à travers Hegel puisait lui aussi chez les<br />

Grecs, n’y aurait sans doute vu que démission la conscience nationale. En réalité,<br />

une réécriture de notre temps est en train d’avoir lieu. Elle cherche ses concepts en<br />

tâtonnant, mais refuse d’aller en profondeur. Son credo c’est la dénationalisation de<br />

la littérature africaine. La dénationalisation de la littérature francophone africaine<br />

aujourd’hui fait cependant écho à sa déracialisation annoncée déjà en 1948 par<br />

Sartre. C’est que la dialectique de l’histoire des peuples dominés est inévitable<br />

dans sa cyclique nécrophagie. Plus pauvres en concepts que nos ainés, des auteurs<br />

africains ont découvert aujourd’hui soudain dans les promesses de la « littératuremonde<br />

en français » et accumulé dans un manifeste publié dans Le Monde, des<br />

mots pour réactualiser, paraphrasons un peu Sartre ici, « la synthèse ou réalisation<br />

de l’humain dans un espace français sans nations », tandis que dans les concepts<br />

d’Édouard Glissant ils ont trouvé l’écume notionnelle pour dire leur continent: «<br />

l’identité-monde ». Dites, comment ne pas rire, car la dialectique est ce couperet<br />

qui ici aussi de cette nouvelle littérature francophone annonce déjà la mort, alors<br />

que le continent africain a encore tant d’histoires à raconter ! C’est le monde (en<br />

français) qu’ils veulent conquérir, nous disent ces auteurs francomondiaux – et ils<br />

croient innover! Les critiques ne peuvent que se réjouir, eux pour le bonheur de<br />

qui la littérature africaine a été réduite par ses propres auteurs a deux librairies<br />

parisiennes. Mais il y a pire cependant que ces balbutiements théoriques, car au<br />

fond, la littérature africaine francophone ne répète que le cercle de sa fuite en avant<br />

qu’on sait déjà, et dont la conclusion au fond a toujours été son anéantissement.<br />

Or cette fois ce n’est plus la négritude ou la nation, c’est la littérature africaine<br />

que ses auteurs mettent sur la balance. Eux qui heureux entérinent la mort de<br />

la littérature francophone dans l’’universel’ de la ‘littérature-monde en français’,<br />

entendent-ils cette voix si proche pourtant qui leur conseille d’inverser le tout,<br />

bref, de revenir au b a ba de la chose littéraire, et leur chuchote un mot qui est un<br />

sésame? Ce mot c’est shümum. Avec lui, c’est l’écriture préemptive qui annonce<br />

une fois de plus son train.<br />

19

20<br />

WORDS ... OLIVE SENIOR<br />

<strong>Olive</strong> <strong>Senior</strong><br />

Her Granddaughter Learns<br />

the Alphabet<br />

I myself had learnt the alphabet, once, long ago,<br />

in a place that was small and known.<br />

But my forgetfulness has grown.<br />

Here, your marks on paper scratch at my heart<br />

as if they were the dragon’s teeth sown,<br />

that split our tongues, that made us scatter,<br />

that made me forget myself, my own alphabet.<br />

I’m a poor guide but I want to erase those scratches,<br />

wipe the slate clean. I’m handing you over<br />

so you can go to places that I have never seen.<br />

This magic leads you on, doesn’t it? These hooks<br />

that pull the sounds fresh from your mouth<br />

and place them in your fist.<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

Donato Ndongo-Bidyogo<br />

Extracto de la novela<br />

Los Hijos de la tribu<br />

PALABRAS ... DONATO NDONGO-BIDYOGO 21<br />

Los Hijos de la tribu es la tercera parte de la trilogía iniciada con Las Tinieblas de<br />

tu memoria negra y continúada en Los Poderes de la tempestad. En ella, el autor<br />

narra la historia de Guinea Equatorial a través de un personaje principal, sin nombre,<br />

símbolo de todo el pueblo e hilo conductor de la saga. Mientras la primera de estas<br />

novelas abarca el período colonial, y la segunda describe los efectos sobre las personas<br />

de la dictadura de Francisco Macías, el primer presidente del país, Los hijos de la tribu<br />

– aún no terminada – comparte con el lector las vicisitudes del pueblo guineano en su<br />

empeño por recuperar la libertad y la dignidad.<br />

En el primer capítulo (al que pertenece el fragmento publicado) se presenta el<br />

ocaso de un régimen personalista, y se sugieren las transformaciones de un país y<br />

de una sociedad decididos a trascender una etapa ominosa para labrar un futuro<br />

esperanzador. Futuro representado por Niña Tasia, la esposa más joven del anciano<br />

déspota, y que contribuirá de modo decisivo al alumbramiento de una nueva<br />

sociedad que saldrá del oscurantismo.<br />

Del capítulo ‘Cero’<br />

Niña Tasia sollozaba acurrucada en el rincón, los ojos velados por las palmas de<br />

sus manos. Antes que la desgracia que caía sobre ella, viuda a los diecinueve años,<br />

le asustaba ser la causa ¿directa? de la muerte de su marido, por las exigencias<br />

de su cuerpo joven que el lujurioso anciano no podía satisfacer; su legendaria<br />

virilidad queda ba reducida a las interminables, exasperantes y monótonas<br />

peroratas oníricas sobre sus hazañas pretéritas, increíbles para ella, a la vista<br />

de la ruina humana que gimió como niño la noche que se reconoció incapaz<br />

de consumar la desfloración; pero, sobre todo, le aterraban las dudas ante su<br />

incierto futuro, cómo reaccionarán los familiares de mi esposo tras los funerales,<br />

me cargarán el muerto sólo porque expiró entre mis piernas, y me maltratarán,<br />

me encarcelarán, o, apartada de mis hijos, seré confinada en mi mísera aldea,<br />

donde apenas he terminado la casa de cemento que mi padre pidió en dote, por<br />

la tacañería proverbial de un fulano considerado entre los magnates más sólidos,<br />

ante el cual doblaban la cerviz los poderosos de la Tierra aunque lo tuvieran por<br />

un choricete basto y advenedizo, cuya ocupación principal y más grata consistía<br />

en recontar cada semana los billetes de divisas que abarrotaban decenas de<br />

maletines diseminados por sus palacetes, cotejar sus numerosas cuentas repartidas<br />

por medio mundo, evaluar sus inversiones en diversas empresas internacionales,<br />

controlando el destino de cada céntimo, y regodearse en la fortuna acumulada<br />

por el chico listo del ínclito Nze Mebiang, cuyos sortilegios de nigromante le

22<br />

PALABRAS ... DONATO NDONGO-BIDYOGO<br />

habían preparado para ser líder entre los líderes y rico entre los ricos. Sesiones de<br />

autoafirmación que culminaban con el visionado de las cintas que mostraban las<br />

lujosas mansiones que poseía allá y acullá en las principales urbes extranjeras y<br />

demás paraísos terrenales, todo ello fruto del latrocinio constante de los recursos<br />

que negaba a su desventurado y mísero pueblo. ¿Para qué tanta avaricia si a la<br />

eternidad se parte tan desnudo como se llega? Y aun cuando todavía no fuese<br />

el tiempo de las plañideras, el luto oficial, Niña Tasia hacía lo imposible por<br />

manifestar su dolor ante la irreparable pérdida, aunque en verdad no sintiese<br />

sino alivio en aquel malhadado trance que daría un vuelco inesperado a su vida:<br />

sólo era otra de las muchas prisioneras perpetuas del serrallo. Necesario actuar<br />

con inteligencia y discreción, ser cauta hasta el detalle, estudiar sus gestos, pasos,<br />

actitudes, palabras, para no dar con sus huesos en las mazmorras del crudelísimo<br />

Esom Esom ni caer víctima de los maleficios brujeriles del fiero Obigli o torturada<br />

con su saña sádica por los perversos y crapulosos sobrinos, todos ahí de pie,<br />

contemplando el cipote desafiante con el que el momio salió victorioso de mil<br />

lances –decían- y que escondía en sí mismo la prueba de su final, que el astuto<br />

hermanísimo quizá no tardara en descubrir. Niña Tasia se arrepentía ahora de<br />

la presteza con la que había dado la voz de alarma al retén de guardia apostado<br />

al otro lado de la puerta cuando, de súbito, el vejete encaramado sobre ella cayó<br />

inerte sobre su cuerpo y cesaron los siempre agónicos y roncos resoplidos: apenas<br />

tuvo tiempo de reaccionar, de pensar. No debió sucumbir al pánico. Conocía bien<br />

los hábitos de la corte de los milagros, cómo se las gastaban los íncubos en las<br />

salvajes noches de aquelarre. Un país en el que los leales eran impunes y todos los<br />

habitantes reos de muerte, con la sola excepción del preboste y su acólito Esom<br />

Esom, único que le humanizaba quizás por su lealtad perruna: aunque dotada<br />

y por tanto tan esposa como las otras, en realidad sólo era la novena concubina<br />

oficial del muy lascivo Jefe Supremo, y tanto su juventud como su condición de<br />

favorita podían volverse contra ella si sus intrigantes rivales se confabulaban<br />

con los allegados del abuelete depravado y decidían sacrificarla para resarcirse<br />

de la desgracia. No era descabellado imaginar tal contubernio. ¿Y si, cumpliendo<br />

la tradición, la desposaba Esom Esom? Lo sabía: ninguna posibilidad de zafarse<br />

al destino; no soportaría ese sino inevitable, no lo soportaría. Lo juró: preferible<br />

el exilio a pertenecer a semejante patán; antes muerta que ser poseída por un<br />

criminal perverso cuyas manos chorreaban tanta sangre inocente.<br />

Se sentía incómoda en el cuarto pestilente, del que tampoco podía huir.<br />

¿Qué hacer? Pensó en su madre. Aunque participara en la conjura familiar para<br />

entregarla al poderoso y decrépito galán, quien con tal unión desmentiría las<br />

habladurías recurrentes sobre el cáncer que le había vuelto impotente, en el fondo<br />

la disculpaba, sabedora de que ella no había encontrado forma de impedir el enlace,<br />

no sólo por no ser capaz de resistir la tiránica coacción de su ambicioso progenitor,<br />

sino porque la negativa acarrea ría males irremediables para la familia y el clan.<br />

Su sacrificio aportaba seguridad y bienestar. ¿Quién osaría negarle algo o molestar<br />

a los parientes de la favorita de Su Excelencia? En aquel mundo de miedo, congoja<br />

y sordidez, era una óptima solución: sus hermanos obtuvieron buenos empleos;<br />

sus cuñados –en realidad sus hermanas- prosperaron; la envidiaban sus amigas;<br />

circulaba en coches imponentes; le sobraba la comida, y enviaba a su madre sacos<br />

enteros de arroz y pescado salado, macarrones, garbanzos y cajas de tomate frito<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

PALABRAS ... DONATO NDONGO-BIDYOGO<br />

enlatado. Los suyos se alimentaban ahora como blancos. Y engordaban. Ella misma<br />

satisfacía sus caprichos más allá de lo inimaginable. Viajaba a Europa para hacerse<br />

la manicura y renovar su ajuar … Bueno, y para … abortar. Dos veces. Doloroso<br />

pensar en esos dos crímenes, matar a los hijos de su único amor. Le indujo a injerir<br />

el fármaco con la misma inocencia – quién sabe si con la misma luciferina<br />

seducción- que cuando le convenció de que los dos primeros embarazos eran<br />

el fruto culminante de su brío sin par. Henchido de soberbia, se lo había tragado.<br />

Increíble la estulticia del viejo majadero. Un verdadero botarate. Mas tenía que<br />

reconocer que ambos amaban con especial devoción a aquellos retoños tardíos:<br />

el padre putativo porque confirmaban ante el mundo incrédulo su potencia<br />

inmarcesible; ella, porque los había concebido en verdaderos actos de amor. Nadie<br />

en la vida sería capaz de descubrir la jugada. Sólo ella conocía su secreto. Pero no se<br />

atrevió a multiplicar el engaño: alguien – las otras, los cuñados, él mismo – podría<br />

dudar de dotes tan portentosas, rayanas en lo milagroso. O puede que su Amor,<br />

herido, proclamara la impostura. Imposible confiar en los hombres, decía su madre,<br />

y por eso abortó. Dos veces. Por su seguridad y prosperidad, y el bienestar de su<br />

familia. Luego conoció los anticonceptivos, y cesaron las noches de zozobra …<br />

Y le había convencido, hacía un instante, de que tomara la píldora; no, dos mejor<br />

que una, el efecto será doble, le animó, sonriente, distendidos sus sensuales labios<br />

carnosos, al aire sus dientes regulares, blanquísimos, su piel clarita, tersa y suave,<br />

y sus hermosos pechos turgentes, rellenitos cuan mango en sazón. Y al poco cayó<br />

desplomado sobre ella, con la cosa bien dispuesta, como nunca había sido, algo<br />

grotesco, vaya. Pareció una broma; luego se asustó y perdió el juicio. El terror la<br />

aniquiló. El Dios de la Justicia era testigo de que no fue su intención. Todo había<br />

sucedido por Su designio. Ella era un mero instrumento de la voluntad del Altísimo.<br />

Nunca se le ocurrió que dos pastillitas pudieran matar. Sólo deseaba divertirse un<br />

poco a costa suya, reír sus gracias, alegrarle la tarde, alimentar su petulancia. Pero<br />

estaba hecho: ninguno creería la verdad, que un puro accidente aceleró la Historia;<br />

había logrado consumar el deseo de medio país; podrían pensar en una<br />

determinación alevosa, hacer de ella una arpía, un monstruo sin entrañas al<br />

servicio de la oposición radical o del terrorismo internacional, una enemiga del<br />

régimen que le daba de comer tan opíparamente, quién sabe si … Y en tal caso …<br />

Quizá … Quizá fuera mejor recrearse en los hechos positivos: tenía sirvientes, era<br />

respetada, temida; la distinguían al pasar, los coros cantaban loas en su honor;<br />

había escalado hasta la cima y podía considerarse ‘alguien’ en la sociedad y no la<br />

niña anónima, flacucha, pobre y bella que fue hasta que bailó para él en aquella<br />

gira por su comarca cuatro años atrás. En ese tiempo, había ido aprendiendo a ser<br />

Señora, según la llamaban sus subordinados y todos, para dejar atrás para siempre<br />

a la inocente y agreste campesina que estaba destinada a ser. Todo ese lustre a<br />

cambio de soportar en silencio sus bufidos, sus repugnantes manoseos, su<br />

horripilante piel macilenta, fofa y arrugada, el hastío de sus besos salivosos, su<br />

asque rosa boca desdentada cuando se quitaba los postizos al dormir. Seguridad<br />

y prosperidad. A cambio de guardar sus secretos, de mentir por omisión, de fingir<br />

siempre, de callar siempre, siempre. No recordaba haber sido joven. Nunca disfrutó<br />

de la vida. Nunca fue feliz. Aunque se daría cuenta mucho tiempo después, al<br />

principio deslumbrada por la ensoñación perpetua a causa de la molicie placentera<br />

en que transcurrían sus días, desde el primer momento había envejecido como él,<br />

23

24<br />

PALABRAS ... DONATO NDONGO-BIDYOGO<br />

obligada a transitar por esas sendas peligrosas para mantener su honor y no<br />

cometer ningún desatino que revolviera el espíritu desalmado del ogro vengativo.<br />

Superar siempre las asechanzas. Saber contener sus emociones. Remontar con<br />

coraje y vigor cuanta adversidad plagaba su funesta existencia en su jaula dorada.<br />

La melancolía como estado permanente, igualito que los animales que viera una<br />

vez en un zoológico de Europa, donde los saltos y la bulla de felinos y monos<br />

carecían de viveza, de la alegría espontánea de las fieras en libertad. Calculando<br />

cada paso, midiendo cada palabra, cada gesto. Tristeza, tristeza infinita reflejada en<br />

sus ojos secos, cansados de llorar. El cuerpo anheloso de ternura, no saciado con la<br />

fingida entrega mercenaria. Asfixiándose en sus cómodos aposentos, celda insufrible,<br />

sin más compañía que los niños, sin asideros, hastiada, el tedio irremediable<br />

de las noches y los días. ¿Había merecido la pena? Recordó los consejos de su<br />

madre, sé fuerte, hija, y muy paciente, y nunca olvides que el éxito de la mujer<br />

radica en la mater nidad y en su capacidad de aguante. Recordó sus caricias<br />

amorosas, su complicidad más allá de la comprensión. Hubiera preferido tenerla<br />

ahora a su lado, refugiarse en sus cálidos brazos para que la guiara en trance tan<br />

azaroso, pero estaba lejos, en el poblado. Se encontraba sola, atrozmente sola.<br />

¿Qué hacer? Aunque … Quizá no estuviese tan sola: él también pensaba en ella,<br />

sí, sin sospechar que le necesitaba más que nunca, que anidarse en su pecho le<br />

consolaba, podía serenarla. Sólo él representaba el indubitable triunfo de la bondad<br />

sobre la maldad, la certidumbre del final de un destino aciago, la honda esperanza<br />

en el esplendor venidero. Sólo él, con su abnegación, aportaba cierta ilusión a una<br />

existencia tan banal. Sólo él podría sufrir con ella, asumir su dolor, compensar las<br />

amarguras. Sólo él, a dos pasos apenas, tras la puerta cerrada, resentido por los<br />

celos, resabiado por el despecho, humillado por la impotencia, carcomido por el<br />

odio, sufriendo en silencio, siempre aguardando impaciente la salida del sátrapa.<br />

Esperando a que le rindiera el letargo de las soporíferas tardes bochornosas y<br />

dormitara en cualquier rincón de sus palacios para acudir a su lado. Aprovechando<br />

cualquier resquicio en el quehacer cotidiano para regalarse con las sobras del viejo<br />

carcamal y poseerla a hurtadillas, fogosa, ardorosa, desesperadamente fundido en<br />

ella como si fuese su última oportunidad antes de la consumación de los siglos.<br />

Soñaba a veces que él le mataba e iniciaban juntos una nueva vida; no podía ser<br />

tan difícil si siempre estaba a un paso tras él, portando su cartera y sus teléfonos<br />

móviles o acercándole el trono para que posara sus voluminosas nalgas flácidas.<br />

Pero ni se atrevía a pensarlo: la fantasía redo blaba su angustia. Determinados<br />

anhelos son más peligrosos, más pecaminosos que la traición carnal, que ese amor<br />

funesto, con dolor de muerte, que les situaba en el filo del desastre, esa pasión<br />

embravecida por el pavor que laceraba sus sentidos en las ausencias y en cada<br />

encuentro. ¿Había merecido la pena? ¿Qué sería de él, de ella, de sus hijitos<br />

inocentes, de su familia toda, ahora que acariciaba la posibilidad de sentirse limpia<br />

y libre por vez primera?<br />

Menos aturdida que cuantos permanecían encerrados en aquella habitación en<br />

penumbra, decorada con primor, infranqueable, sellada, Niña Tasia se dispuso a<br />

esperar. Ninguno sabía qué, y poco importaba, pero debían hacer de la necesidad<br />

virtud. Pensar. Sopesar. Calcular. Relegar al transcurso del tiempo la solución de<br />

todos los enigmas. Quizás hubiesen llegado al final de la partida. Quizá ya sonaran<br />

a lo lejos las trompetas de Jericó. O quizá no todo estuviese perdido y quedara<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

PALABRAS ... DONATO NDONGO-BIDYOGO 25<br />

alguna rendija por donde hallar la salvación. Seres despiadados, brutales, ahora<br />

embotados por la bruma de sus almas atormentadas, intuían el ocaso de su era,<br />

e imploraban, humildes y fervorosos, a sus espíritus protectores, y a todos los dioses<br />

del Universo, la suficiente presencia de ánimo para controlar la situación y salir<br />

con bien. No debían precipitarse. Nunca desfa llecer, porque era posible el milagro:<br />

Su Excelencia el Mariscal de Campo Don Gumersindo Nze Ebere Ekum, Presidente<br />

de la República, Jefe de Estado y del Gobierno, Coman dante en Jefe de los Ejércitos<br />

y Presidente-Fundador del Partido para el Bienestar del Pueblo, Invicto Caudillo y<br />

Guía Supremo de la Nación, había salido indemne de la prueba final, y en cualquier<br />

instante resurgiría de entre los muertos para restaurar el orden secular y la paz<br />

y armonía felizmente reinantes en el país.<br />

(Trabajo en curso, 2010)

26<br />

WORDS ... ESTHER HEBOYAN<br />

Esther Heboyan<br />

The Picture Bride<br />

So I wrote this story, a story in black-and-white pictures of the sort purveyed over<br />

the years by Ara Güler’s ‘Istanbul’ and Robert Doisneau’s ‘Paris’, the two sonorous<br />

cities of my life (but that is another story; let us not get carried away). I wrote this<br />

story about a picture bride, a type one finds in the hamlets of ancient Anatolia as<br />

well as in the cosmopolitan quarters of Urbania.<br />

This picture bride, known as Aghavni Tchamitchyan, wore a melancholy smile<br />

in the pictures that journeyed by mail to strange lands, awaited by a Mardiross<br />

in São Paulo, a Hrant in Montreal, a Zaven in Lisbon, a Dikran in Johannesburg,<br />

a Mihran in Abidjan, a Theodoros in Salonika and, finally, a Garbiss in Vienna.<br />

However, for Aghavni, who had been pining away in her parents’ record store at<br />

Beyo-lu, a hole in the wall wedged between a cigarette stand and a trinket trade<br />

of some sort, none of those fervently auditioned and photographed suitors seemed<br />

to possess the good looks and stamina of her Elvis, the one and only, her prince,<br />

her pasha, for now and forever.<br />

‘I’d rather not,’ she would say to her parents, who had happily married off three<br />

elder daughters.<br />

Off to Melbourne flew beautiful Nadya: husband running a jewelry store, one<br />

daughter fluent in Australian English and Western Armenian. Off to New York<br />

sailed generous Zepur: wife to a delicatessen owner, mother of two healthy boys.<br />

As for bright Sonya, who settled so glamorously in Vienna, going to the opera and<br />

so on, in the wake of her husband – a doctor – she did, at one point, nurture hopes<br />

of introducing her youngest sister to an interesting fellow versed in Mekhitarist<br />

theology and miniature painting. But Aghavni failed to show any interest in<br />

Garbiss the Viennese.<br />

‘What’s wrong with you?!’ her parents would exclaim, taking turns. And then,<br />

to each other: ‘What’s wrong with her?’<br />

Bending over like a tilting snowdrop, elbows resting on the star-studded glass<br />

counter, Aghavni’s brain, eyes and ears filled with the velvety voice of Elvis Presley;<br />

the young woman thus whiled away her time in a side alley of Istanbul’s heartbeat.<br />

Rain, sleet or snow, she was welcoming even when other people groaned and<br />

grumbled. On such days she shut the door, which sported an unfortunate sign<br />

– THIS SHOP IS O<strong>PEN</strong> – and ecstatically turned up the volume of the German<br />

gramophone to rock, body and soul, to the King’s tremors, until her father or<br />

mother stomped in to curb her foolishness. Sometimes a customer entered,<br />

much to Aghavni’s dislike, with a view to rummaging through the vinyl singles<br />

she had tenderly arranged. Or worse, he would dart about with lurid glances, as<br />

though, instead of a shop entrance, he had come across a bright orange light bulb<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

WORDS ... ESTHER HEBOYAN 27<br />

disentangling him from family, home and decency.<br />

Now and then, an Armenian youth posing as a lover of à la franga music<br />

walked in, faking a purchase of Adamo’s ‘Tombe la neige’ or Cliff Richard’s ‘Living<br />

Doll’. But somehow Aghavni knew the 45-rpms were most likely destined for a<br />

sibling or cousin. She could also tell the young men had been dispatched there<br />

by a conspiring trio that included her dutiful mother, her just-as-dutiful godmother<br />

and a despicable matchmaker fattened on gold, dolmas and lies. The most<br />

disheartening fact: those young Armenian men, dashing and well-intentioned<br />

though they might be, would unrepentantly enjoy nothing but à la turka music<br />

unto their grave. And she, Aghavni Tchamitchyan, who truly craved the mellow<br />

foreign sounds and undecipherable lyrics of unreachable rockers and crooners,<br />

would forever be denigrated by a houseful of in-laws and perhaps be banished<br />

to the back room to listen to Elvis purr and pulse on a second-hand Grundig:<br />

Are you lonesome tonight?/Do you miss me tonight?/Are you sorry we drifted apart?<br />

Aghavni cried her heart out when her Elvis, the one and only, her prince, her<br />

pasha, to whom she had secretly vowed infinite, fecund love, took for a spouse a<br />

certain Priscilla Beaulieu, who smiled from every newspaper and magazine cover.<br />

The caption invariably read: ‘The King has found his Queen.’ Elvis’s bride looked like<br />

a queen, all right. On all the pictures – without exception. Whether photographed<br />

full-face or in profile, that Priscilla looked as though she were made of silver and<br />

pearl, so pretty in her lush white gown and rippling raven hair adorned with an<br />

ethereal bridal veil.<br />

Aghavni wept for days. At first, she devoted herself to cutting out the<br />

newspaper clippings and the black-and-white pictures while she wept. Then<br />

she wept while gazing at the pictures and reading the articles. For two months,<br />

she stayed in her bedroom above the tiny record shop, shedding tears, blowing<br />

her nose into an unattractive feature, listening to Elvis’s amorous voice for<br />

hours on end.<br />

‘What’s wrong with you?’ yelled her parents, taking turns. They flailed their<br />

arms and shook their heads, but mostly tss-tssed as Oriental parents are wont<br />

to do.<br />

To make matters worse, moreover, they now had to run the shop themselves,<br />

and to explain their daughter’s illness to all who would listen. ‘What’s wrong with<br />

her?’ they asked each other again, once acquaintances and customers were out<br />

of sight.<br />

As Aghavni Tchamitchyan chewed on her misery, sudden hope materialised for<br />

Nazar Nazarian of Paris. There, in that world-famous capital city, in his very wallet,<br />

trilled the most promising picture bride of all time. Somehow, the destiny of this<br />

one lonely soul had to merge with that of another.<br />

This is when I came into the picture to write this story of this black-and-white<br />

bride coveted by lonesome Nazar. I went through three family albums to find my<br />

picture bride, the kind whose life story is either totally lost to younger generations<br />

or dealt out in bits and pieces. This one, with the wry smile? No one could<br />

remember, as though she happened to be an unwanted guest at her own wedding.<br />

That one, wearing the tiara? That must be, let me think, that must be chubby<br />

Artin’s eldest daughter, what was her name, by the way? Oh, look at this one, a<br />

legend in her time, a true nightingale, and such grace. And wasn’t that one called

28<br />

WORDS ... ESTHER HEBOYAN<br />

Astrig, you know, the girl from the Adana orphanage, the one who was married<br />

to her foster parents’ son?<br />

To my utter amazement, not one Aghavni Tchamitchyan leaped out of the<br />

yellowing pages. Further research proved necessary in the homes of friends and<br />

relatives, all transplanted to distant lands with sets of photographs. To write<br />

a simple story, I thought, one goes a long ways off. Apparently luck, or fate, or<br />

whatever you call it, never quite fits the time and place a storyteller selects.<br />

Therefore I had Nazar Nazarian of Paris come across the snapshot of Aghavni<br />

Tchamitchyan by pure chance. A travelling friend of his, having journeyed all the<br />

way to Salonika, had been so enamoured with Aghavni’s picture that he handed it<br />

over to Nazar as a proof of their manly friendship. At the time, Nazar was regaining<br />

the confidence to want a second wife. The quest took the form of a long letter, plus<br />

a black-and-white photograph of the awaiting groom in front of the Eiffel Tower.<br />

‘That one?!’ howled the intended bride. ‘You can let him rot, in Paris or not!’<br />

Whereupon her parents tss-tssed in their parental manner and passed the pictured<br />

groom to relatives in Tarlabas Tarlabasi, , who were evidently cursed with a worse case in<br />

their own home.<br />

At the other end of the postal route, Nazar Nazarian of Paris kept up his<br />

expectations. Never a womaniser like his cousin Garo, a near twin, to whom he<br />

had been inevitably compared all those years – forty-three years, if one wished<br />

to keep track – he grew adamant about finding his other half, she palatable like<br />

dough cut into halves and laid on the kitchen counter before kneading, a herald<br />

of festivities. Nazar loved Aghavni’s picture: a young Armenian woman from<br />

Constantinople, a face daintily chiselled, a full-fledged body in modern dress, which<br />

modestly covered her knees and shoulders. A perfect match, he thought to himself.<br />

What Nazar liked about Aghavni most: she was born almost the same day as he,<br />

a sure sign of fate; she lived in Constantinople, he on the Rue de Constantinople by<br />

Gare Saint-Lazare; she had been christened ‘Aghavni’, like his ailing mother, and he<br />

was also very fond of the aghavnis that flew to his balcony – every day he would<br />

feed those birds, contemplating them, talking to them and playing his saz to on<br />

drowsy Sunday afternoons.<br />

It was on one such afternoon in Paris that Nazar’s mother, who lived in a<br />

two-room apartment below his, after hearing her son strum the saz listlessly,<br />

encouraged him to hunt for another wife in their city’s Armenian circles. But Nazar<br />

would have none of it. The second-generation Armenian girls in Paris did not speak<br />

Armenian, or cook Armenian. Many smoked, wore miniskirts and ran around with<br />

French men. Like his first wife. A whore, according to his mother. Gone with their<br />

shop assistant, after eight months of conjugal life.<br />

From his mother’s vengeful fury, Nazar had salvaged a snapshot taken on the<br />

beach at Saint-Raphaël, a picture of happy newlyweds in summertime. It had been<br />

their only vacation: she left him in the fall. Nazar didn’t miss her as a person, or as a<br />

wife (how could he?). But he missed her warmth, her brown body, her laughter, too.<br />

‘Too loud, too loud, she laughs like a whore,’ his mother would harp. Nazar winced<br />

at the memory.<br />

‘Well, well, well, show me that would-be bride of yours,’ intoned Nazar’s<br />

mother at teatime, settled in her armchair by the window. ‘Oh, my! Look at all the<br />

excrement on the balcony! My son, are you building Noah’s Ark, with pigeons up<br />

WiPC 50 Years, 50 Cases

WORDS ... ESTHER HEBOYAN 29<br />

there? What’s wrong with you?’<br />

The son poured the tea, nicely brewed as in the old country, and served a plate<br />

of kurabiye he had purchased at the Armenian grocery by the Métro Cadet. He put<br />

on his mother’s favourite song by Safiye Ayla, Kâtibim. His mother began humming<br />

along:<br />

Üsküdar’a gider iken aldı da bir ya˘gmur … Kâtibimin setresi uzun, ete˘gi çamur …<br />

Kâtip uykudan uyanmis, gözleri mahmur … Kâtip benim ben kâtibin, el ne<br />

karsır …<br />

Casting a glance at her own wedding picture on the wall, she sighed. Once so<br />

young, now so old. ‘So, my son, are you or are you not going to show me that bride<br />

of yours?’<br />