Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

artist in residence<br />

He was supplied a car and a chauffeur and every day drove<br />

along the path of the Columbia, looking out at the countryside,<br />

the Grand Coulee Dam and the Bonneville Dam, talking with<br />

rural farmers whose economic outlook had radically improved<br />

because of hydroelectric power, drawing and writing songs. In<br />

the afternoon, he’d work out his compositions on guitar and<br />

then return to the office to record and transcribe them.<br />

Kahn’s emergency intervention had given the tumbleweed<br />

troubador a brief respite from his troubles, and provided<br />

a modicum of stability for the Guthrie family in the little<br />

apartment they had rented on Portland’s Southeast 92nd Street.<br />

In Guthrie’s stormy life it was a month of calm and security.<br />

The verdant land surrounding the Columbia in the gentle<br />

warmth of spring seemed like Eden, and during this time he<br />

wrote a song that many view as his masterpiece: “Pastures of<br />

Plenty,” about poor migrant farm workers leaving Oklahoma to<br />

look for work picking fruit in the Pacific Northwest.<br />

It’s clearly drawn from Grapes of Wrath, a book Guthrie read<br />

for the first time in Portland (Kahn had given it to him), but<br />

the fact that he wrote it while tromping around Oregon in the<br />

springtime reveals the masterpiece in a new light.<br />

He’s using what he learned from his time with the migrant<br />

workers in California,” Burke said. “In the song ‘Pastures of<br />

Plenty,’ he’s also singing about the Pacific Northwest. He’s<br />

singing about the part of the country that we live in. The<br />

pastures of plenty are real, and the hope in that song springs<br />

out of the hardships that working people endured, that brought<br />

them here for a chance at a better life.”<br />

Guthrie left Portland three days early thanks to vacation<br />

days he’d earned as “information consultant.” He picked up<br />

his check and hit the road—without his wife and family—and<br />

his first marriage had disintegrated by the time he hitchhiked<br />

back to New York. Back in New York he joined the Almanac<br />

Singers, then served as a Merchant Marine in World War II.<br />

In the ’50s he was diagnosed with Huntington’s Disease, a fatal<br />

genetic brain disorder that left him without the ability to speak<br />

for fifteen years before his death in 1967.<br />

Years later, when Murlin found a letter from Guthrie noting<br />

he had written twenty-six songs for the government, he set<br />

out to find them. An article on Murlin’s discovery sparked a<br />

nationwide search for the missing songs, which would become<br />

known collectively as the Columbia River Songbook. Guthrie’s<br />

original wax cylinders he’d recorded at the Portland office<br />

were long gone, but every day Murlin unwrapped packages<br />

sent to him from dusty New York attics, forgotten studio<br />

archives, and the storage spaces of Guthrie’s friends and<br />

relatives. Gradually Murlin found all the songs. The BPA, in<br />

collaboration with The Smithsonian and The Woody Guthrie<br />

Center in Oklahoma, released the Columbia River Collection<br />

in 1988 with an accompanying book of music called the<br />

Columbia River Songbook.<br />

In 2017, Murlin released a new edition of the songbook to<br />

honor the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Columbia River<br />

Songs. Along with Joe Seamons, he created a new recording<br />

containing all twenty-six songs for the first time, sung by<br />

Northwest artists.<br />

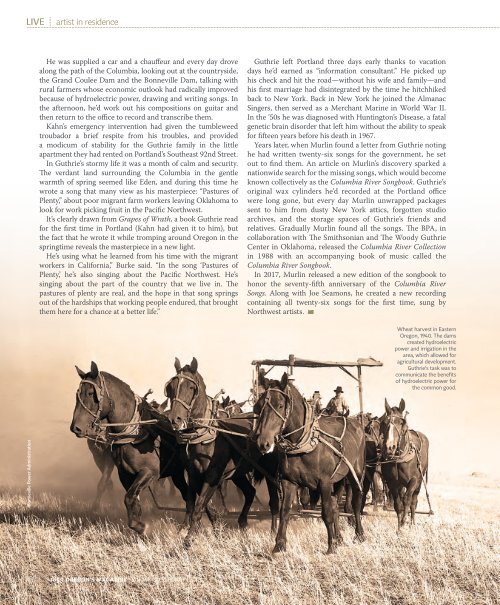

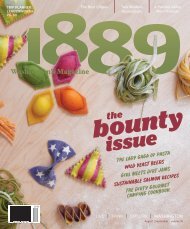

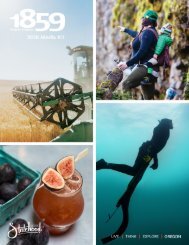

Wheat harvest in Eastern<br />

Oregon, 1940. The dams<br />

created hydroelectric<br />

power and irrigation in the<br />

area, which allowed for<br />

agricultural development.<br />

Guthrie’s task was to<br />

communicate the benefits<br />

of hydroelectric power for<br />

the common good.<br />

Bonneville Power Administration<br />

60 <strong>1859</strong> OREGON’S MAGAZINE JANUARY | FEBRUARY <strong>2018</strong>