You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

home + design<br />

Andrew Pogue<br />

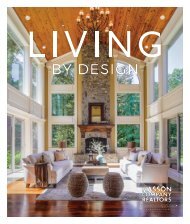

FROM LEFT The model features a long exterior breezeway. Blonde bamboo floors and large windows welcome light into the space.<br />

construction versus a custom build. Prefab, short for prefabricated,<br />

applies to structures that are primarily manufactured in an off-site<br />

factory. Prefab was first made popular in the United States from<br />

1908 to 1940, when Sears, Roebuck and Co. sold 75,000 mail-order<br />

kit homes. While residential prefab building continued throughout<br />

the twentieth century, it regained in prominence when a plethora<br />

of modern architects returned to the form, as promoted in a 2003<br />

design contest sponsored by Dwell magazine. Staupe and Roy<br />

were searching for a prefab builder who clicked with their personal<br />

aesthetic, and found one in an unlikely place: the freeway. Roy was<br />

driving when he saw an intriguing module from Method Homes<br />

being transported on a trailer.<br />

Brian Abramson co-founded the Seattle-based Method Homes<br />

in 2008 and specializes in architect-designed, modular prefab<br />

construction. “Modular refers to large, volumetric modules that<br />

are mostly finished, then transported to the site,” Abramson said.<br />

Modern prefab homes like his can tackle two major problems<br />

in the construction industry—waste and energy efficiency. “By<br />

building off-site, we’re able to reduce the waste generated and<br />

reuse a lot of our scraps,” Abramson said. Additionally, if builders<br />

use newer technologies like structurally insulated panels, they can<br />

reduce a home’s carbon dioxide emissions and increase energy<br />

efficiency. “One of our core missions is sustainability, so even with<br />

our most baseline homes, we build well-above code,” Abramson<br />

said. His models come with a suite of environmentally friendly<br />

features, including low- or no-VOC paints and adhesives, no-UA<br />

formaldehyde in the building materials, FSC-certified hardwood<br />

floors, above-code insulation, energy efficient appliances and lowflow<br />

fixtures.<br />

After visiting Method’s factory in Ferndale, Staupe and Roy<br />

appreciated the company’s craftsmanship and green qualities, as<br />

well as the potential to customize their pick. During the design<br />

phase, they selected finishes, expanded and added windows, and<br />

tweaked the principle suite to fit a tub. Even better, once plans were<br />

finalized, construction was quick—just three months for fabrication<br />

in the factory, during which the foundation was poured on-site and<br />

the garage built. “Once they actually delivered the modules to the<br />

site, they had us in within just over two months,” Staupe said. “It was<br />

an incredibly fast process, and it felt even faster because we had a<br />

baby right towards the end!”<br />

The couple chose the Shift Model, designed by architect Ryan<br />

Stephenson of Stephenson Design Collective. For it, he stacked two<br />

modules, then “pushed them apart” to form a long, shaded exterior<br />

breezeway, which connects copious deck space and extends the<br />

interior living outdoors. The exterior was then faced with charcoal<br />

standing-seam metal and untreated cedar, which will patina to a<br />

silver-gray over time.<br />

At the entry, visitors are met with a stunning handcrafted<br />

bookcase, another customization requested by the couple. “It’s a real<br />

‘wow’ factor when you walk into the house,” Staupe said. Behind it,<br />

a staircase composed of floating concrete tread leads upstairs, while<br />

a nearby flex space can be used for an office or play area, depending<br />

on the family’s needs. Hallways on the perimeter of the first floor<br />

create easy circulation, flowing into an open kitchen, dining and<br />

living room. At the center, a necessary support beam is disguised<br />

with additional built-in shelves and a three-sided fireplace, which<br />

gently separates the rooms and provides a natural gathering spot.<br />

“I’m one of those people who would sit on top of a heater if I could,”<br />

Staupe said. “So I frequently sit right there.”<br />

During the design process, the couple “were really inspired by the<br />

Scandinavian aesthetic and what they do to welcome light into the<br />

house,” Staupe said. To that end, blonde bamboo floors meet crisp<br />

white walls, and kitchen cabinets in the same wood are wrapped<br />

with snowy quartz counters. Additionally, the enlarged windows<br />

bring in plenty of sunlight no matter the season. Thanks to the<br />

home’s more narrow footprint, the effect is that of being surrounded<br />

by the natural setting, which is just what the family wanted. “We<br />

bought our property because we loved the views,” Staupe said.<br />

Since moving into their home in 2013, Staupe and Roy have<br />

acclimated well to their new life, despite having been city dwellers<br />

for decades. “The house is such a welcome, comfortable place to<br />

come home to,” Staupe said. Moreover, their two young children<br />

are having a blast, whether they’re building mud kitchens, spinning<br />

in tree swings or racing scooters down dirt hills. “Between the<br />

property and the house itself,” Staupe said, “it’s kind of a dream for a<br />

child to grow up in.”<br />

28 <strong>1889</strong> WASHINGTON’S MAGAZINE FEBRUARY | MARCH <strong>2018</strong>