Historic Laredo

An illustrated history of the city of Laredo and the Webb County area, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

An illustrated history of the city of Laredo and the Webb County area, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

❖<br />

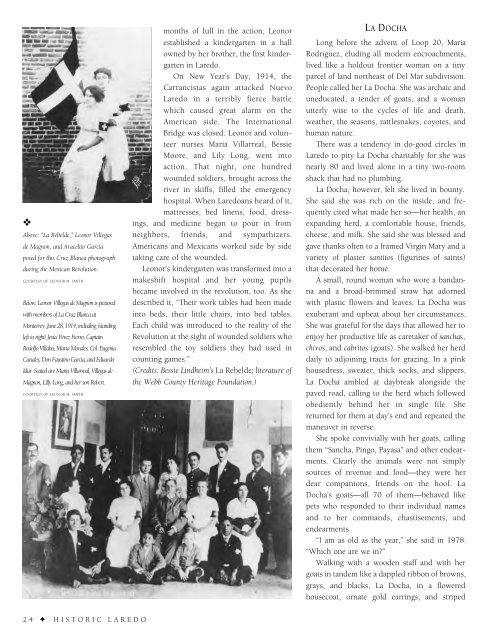

Above: “La Rebelde,” Leonor Villegas<br />

de Magnon, and Aracelito García<br />

posed for this Cruz Blanca photograph<br />

during the Mexican Revolution.<br />

COURTESY OF LEONOR M. SMITH<br />

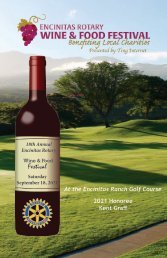

Below: Leonor Villegas de Magnon is pictured<br />

with members of La Cruz Blanca at<br />

Monterrey, June 28, 1914, including (standing<br />

left to right) Jesús Pérez Fierro, Captain<br />

Rodolfo Villaba, María Morales, Col. Eugenia<br />

Canales, Don Faustino García, and Eduardo<br />

Idar. Seated are María Villarreal, Villegas de<br />

Magnon, Lilly Long, and her son Robert.<br />

COURTESY OF LEONOR M. SMITH<br />

months of lull in the action, Leonor<br />

established a kindergarten in a hall<br />

owned by her brother, the first kindergarten<br />

in <strong>Laredo</strong>.<br />

On New Year’s Day, 1914, the<br />

Carrancistas again attacked Nuevo<br />

<strong>Laredo</strong> in a terribly fierce battle<br />

which caused great alarm on the<br />

American side. The International<br />

Bridge was closed. Leonor and volunteer<br />

nurses María Villarreal, Bessie<br />

Moore, and Lily Long, went into<br />

action. That night, one hundred<br />

wounded soldiers, brought across the<br />

river in skiffs, filled the emergency<br />

hospital. When <strong>Laredo</strong>ans heard of it,<br />

mattresses, bed linens, food, dressings,<br />

and medicine began to pour in from<br />

neighbors, friends, and sympathizers.<br />

Americans and Mexicans worked side by side<br />

taking care of the wounded.<br />

Leonor’s kindergarten was transformed into a<br />

makeshift hospital and her young pupils<br />

became involved in the revolution, too. As she<br />

described it, “Their work tables had been made<br />

into beds, their little chairs, into bed tables.<br />

Each child was introduced to the reality of the<br />

Revolution at the sight of wounded soldiers who<br />

resembled the toy soldiers they had used in<br />

counting games.”<br />

(Credits: Bessie Lindheim’s La Rebelde; literature of<br />

the Webb County Heritage Foundation.)<br />

LA DOCHA<br />

Long before the advent of Loop 20, María<br />

Rodriguez, eluding all modern encroachments,<br />

lived like a holdout frontier woman on a tiny<br />

parcel of land northeast of Del Mar subdivision.<br />

People called her La Docha. She was archaic and<br />

uneducated, a tender of goats, and a woman<br />

utterly wise to the cycles of life and death,<br />

weather, the seasons, rattlesnakes, coyotes, and<br />

human nature.<br />

There was a tendency in do-good circles in<br />

<strong>Laredo</strong> to pity La Docha charitably for she was<br />

nearly 80 and lived alone in a tiny two-room<br />

shack that had no plumbing.<br />

La Docha, however, felt she lived in bounty.<br />

She said she was rich on the inside, and frequently<br />

cited what made her so—her health, an<br />

expanding herd, a comfortable house, friends,<br />

cheese, and milk. She said she was blessed and<br />

gave thanks often to a framed Virgin Mary and a<br />

variety of plaster santitos (figurines of saints)<br />

that decorated her home.<br />

A small, round woman who wore a bandanna<br />

and a broad-brimmed straw hat adorned<br />

with plastic flowers and leaves, La Docha was<br />

exuberant and upbeat about her circumstances.<br />

She was grateful for the days that allowed her to<br />

enjoy her productive life as caretaker of sanchas,<br />

chivos, and cabritos (goats). She walked her herd<br />

daily to adjoining tracts for grazing. In a pink<br />

housedress, sweater, thick socks, and slippers,<br />

La Docha ambled at daybreak alongside the<br />

paved road, calling to the herd which followed<br />

obediently behind her in single file. She<br />

returned for them at day’s end and repeated the<br />

maneuver in reverse.<br />

She spoke convivially with her goats, calling<br />

them “Sancha, Pingo, Payasa” and other endearments.<br />

Clearly the animals were not simply<br />

sources of revenue and food—they were her<br />

dear companions, friends on the hoof. La<br />

Docha’s goats—all 70 of them—behaved like<br />

pets who responded to their individual names<br />

and to her commands, chastisements, and<br />

endearments.<br />

“I am as old as the year,” she said in 1978.<br />

“Which one are we in?”<br />

Walking with a wooden staff and with her<br />

goats in tandem like a dappled ribbon of browns,<br />

grays, and blacks, La Docha, in a flowered<br />

housecoat, ornate gold earrings, and striped<br />

24 ✦ HISTORIC LAREDO