Historic Louisiana

An illustrated history of Louisiana, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the state great.

An illustrated history of Louisiana, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the state great.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CHAPTER II<br />

THE CREOLE TRANSITION, 1780-1830<br />

In 1803, <strong>Louisiana</strong> did not spring joyfully into America’s arms. In the eighteenth century, she<br />

was European and African, not American. But by the 1850s she was a fully Southern state of the<br />

Union. The era between the two conditions was the Creole transition. It was a Creole time because<br />

native-born people with mixed European and African roots played a significant role in the<br />

economy, government, and culture. This variegated state of affairs prevented any one racial, ethnic,<br />

or political group from achieving dominance. The happy consequence was a grudging tolerance<br />

that facilitated free speech, free love, and free spirits. New Orleans acquired its enduring reputation<br />

as a party town.<br />

The Creole transition began in the 1770s under Spanish sovereignty, a comparatively happy,<br />

tolerant, and prosperous time. While the American Revolution was underway, between 1779 and<br />

1781 <strong>Louisiana</strong> military forces won three battles, capturing English forts at Baton Rouge, Mobile,<br />

and Pensacola. The Spanish welcomed the Acadians and the Isleños. They provided free land to<br />

them and to many Americans moving westward from the English colonies facing the Atlantic<br />

Ocean. Spanish governors were among the best <strong>Louisiana</strong> has ever had, from Bernardo de Gálvez<br />

and Estevan Miró to François-Louis Hector, baron de Carondelet. But at the turn of the century the<br />

Spanish empire popped like a giant balloon struck by the lightning generated by the French<br />

Revolution.<br />

The arrival of refugees from Haiti between the years 1794 and 1810 gave the French influence<br />

in <strong>Louisiana</strong> its greatest boost since the 1720s. In 1809, 3,102 free blacks and 2,731 whites came<br />

to New Orleans, accompanied by 3,226 slaves. They all spoke French. Among the many<br />

distinguished Haitian refugees were attorney Louis Moreau-Lisle, and professors Jules Davezac and<br />

Pierre Lambert of the Collège d’Orléans. The significance of the Haitian influx was the increase it<br />

gave to the French-language whites, slaves, and free blacks.<br />

The long-term significance of the Creole transition was the appearance of a group of people of<br />

mixed racial background. For almost a century this group, known first as Free People of Color,<br />

lived an influential and quasi-free life in <strong>Louisiana</strong>. It ended in the 1890s as legal segregation<br />

clamped down on both freedmen and former Free People of Color.<br />

Free People of Color included those of entirely one race, as well as many descendants of<br />

interracial unions. In Natchitoches the first families all produced sons who married Indian women.<br />

These included Pierre Bertrand, Louis Joseph Blanpain, Jean Baptiste Brevel, and Barthelemy<br />

LaCour. Others created families of mixed French and African heritage, notably the Metoyer family.<br />

In Pointe Coupée Parish many Creoles created families with African woman, notably brothers<br />

Antoine and Joseph Decuir. In New Orleans in 1760, two French brothers arrived from Provence.<br />

Louis and Jean-François Dolliole sailed to America from La Seyne sur Mer near Toulon on France’s<br />

Mediterranean coast. Jean-François Dolliole began a decades-long liaison with a free woman of<br />

color named Catherine, who most likely came from Africa, and became father to four children of<br />

color. His brother, Louis, did much the same thing, mating with a woman named Geneviéve<br />

“Mamie” Larronde, most likely from the French West Indies, and producing four offspring. The<br />

younger Vincent Rillieux produced several sons with his partially African wife Constance Vivant—<br />

Edmond, Bartolome, and Norbert Rillieux. Edmond became a New Orleans builder. Norbert<br />

invented the vacuum pan process for the manufacture of sugar.<br />

One of the achievements of the Creole transition was the creation of the unique <strong>Louisiana</strong> system<br />

of civil law. Based on Spanish and French precedents, in the nineteenth century it made <strong>Louisiana</strong> the<br />

most progressive state in the Union for family law. In the rest of the country the husband was head of<br />

the house and free to sell and dispose of all of the private estate without consulting anyone, especially<br />

✧<br />

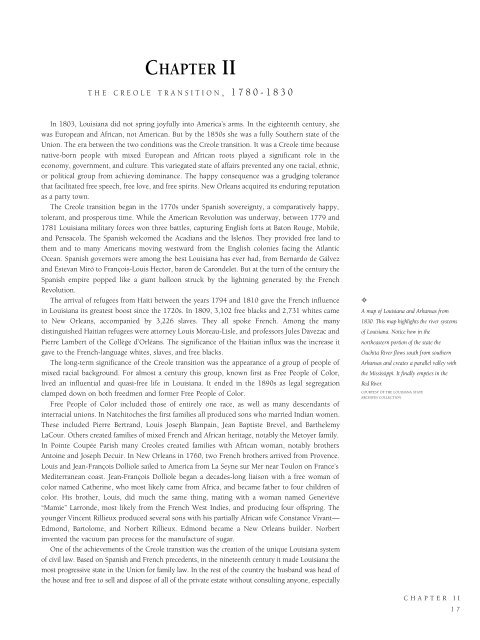

A map of <strong>Louisiana</strong> and Arkansas from<br />

1830. This map highlights the river systems<br />

of <strong>Louisiana</strong>. Notice how in the<br />

northeastern portion of the state the<br />

Ouchita River flows south from southern<br />

Arkansas and creates a parallel valley with<br />

the Mississippi. It finally empties in the<br />

Red River.<br />

COURTESY OF THE LOUISIANA STATE<br />

ARCHIVES COLLECTION.<br />

CHAPTER II<br />

17