Historic Louisiana

An illustrated history of Louisiana, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the state great.

An illustrated history of Louisiana, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the state great.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

✧<br />

Above: Bernardo de Gálvez (1746-1786)<br />

was a military leader akin to Pierre Le<br />

Moyne d’Iberville. His lasting importance to<br />

<strong>Louisiana</strong> was a result of his three successful<br />

military campaigns during the<br />

Revolutionary War in which Gálvez’s<br />

Spanish forces drove British troops from<br />

forts at Baton Rouge, <strong>Louisiana</strong>; Mobile,<br />

Alabama; and Pensacola, Florida. These<br />

Spanish territories would later fall into the<br />

waiting lap of America instead of remaining<br />

British outposts whose importance would<br />

have greatly magnified the danger to New<br />

Orleans in 1815. Gálvez married a Creole<br />

widow who named the Feliciana parishes.<br />

COURTESY OF THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS<br />

COLLECTION, 1991.34.15.<br />

water’s edge. Soon after 1770, Bordeaux shipbuilder<br />

Arnold Magnon opened a yard on the<br />

riverbank adjacent to the Ursuline Convent.<br />

In 1780 when Bernardo de Gálvez planned<br />

his attack on Pensacola, he needed a flotilla of<br />

thirty-two vessels. Magnon worked on many<br />

of them. He successfully kept his shipyard<br />

operating in front of the city until 1819,<br />

employing as many as twenty-six slaves.<br />

Another early shipbuilder just down river<br />

from Magnon was Andre Seguin. With the<br />

onset of the embargo of 1808, the U.S. Navy<br />

presence in New Orleans dramatically<br />

increased. The local commander, David<br />

Porter, received three hundred feet along the<br />

river front between Dumaine and St. Philip<br />

Streets to use as a navy dockyard.<br />

In 1819 the city council evicted<br />

shipbuilding from the New Orleans side, so<br />

shipbuilders moved across the river to Algiers.<br />

That very year the owner of Algiers point,<br />

Bernard Duverjé, began subdividing his tract<br />

of land. The first shipbuilder to move was<br />

Seguin. By 1842 half the population of Algiers<br />

was in the shipbuilding business. The greatest<br />

antebellum shipbuilder was Peter Marcey. Dry<br />

docks were a staple of the ship repair business,<br />

and the earliest dry docks appeared at Algiers<br />

by 1840. Eleven different dry docks lined the<br />

Algiers river front before 1860. The largest was<br />

the Pelican Dry Dock, which could lift a vessel<br />

four hundred feet in length. There were eight<br />

shipbuilding firms in Algiers by 1850. The<br />

Confederate abandonment of New Orleans led<br />

to the destruction of some shipbuilding<br />

property, but the presence of the Union<br />

fleet insured much work for the duration of<br />

the war.<br />

After the Civil War shipbuilding<br />

transformed itself from a branch of carpentry<br />

to a branch of metallurgy. In 1903 the Algiers<br />

Iron Works and Dry Docks appeared just<br />

upstream from the Canal Street ferry. A dry<br />

dock remains at this site to this day. At the<br />

turn of the century, Lewis Johnson moved<br />

his ironworks across the river. The firm was<br />

one of the largest in the city, and it went<br />

into ship repair. In the 1950s it became the<br />

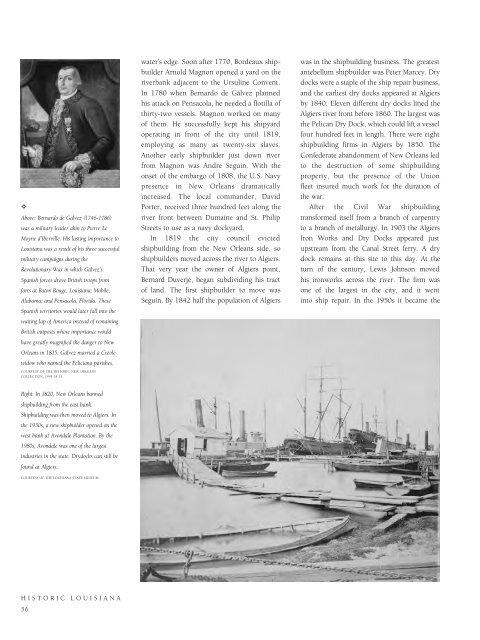

Right: In 1820, New Orleans banned<br />

shipbuilding from the east bank.<br />

Shipbuilding was then moved to Algiers. In<br />

the 1930s, a new shipbuilder opened on the<br />

west bank at Avondale Plantation. By the<br />

1980s, Avondale was one of the largest<br />

industries in the state. Drydocks can still be<br />

found at Algiers.<br />

COURTESY OF THE LOUISIANA STATE MUSEUM.<br />

HISTORIC LOUISIANA<br />

56