Historic Louisiana

An illustrated history of Louisiana, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the state great.

An illustrated history of Louisiana, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the state great.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

✧<br />

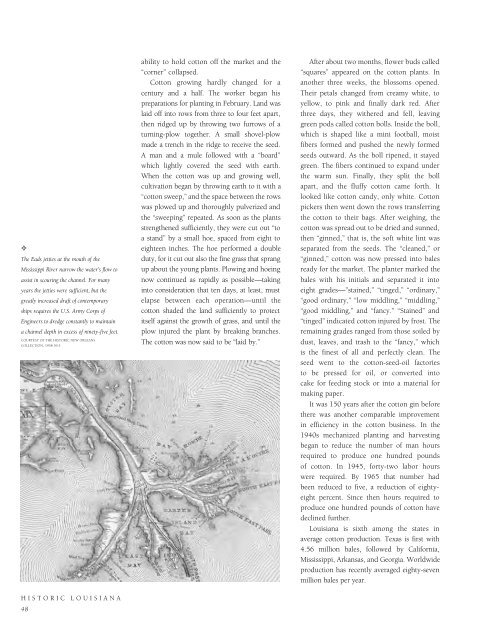

The Eads jetties at the mouth of the<br />

Mississippi River narrow the water’s flow to<br />

assist in scouring the channel. For many<br />

years the jetties were sufficient, but the<br />

greatly increased draft of contemporary<br />

ships requires the U.S. Army Corps of<br />

Engineers to dredge constantly to maintain<br />

a channel depth in excess of ninety-five feet.<br />

COURTESY OF THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS<br />

COLLECTION, 1958.59.5<br />

HISTORIC LOUISIANA<br />

48<br />

ability to hold cotton off the market and the<br />

“corner” collapsed.<br />

Cotton growing hardly changed for a<br />

century and a half. The worker began his<br />

preparations for planting in February. Land was<br />

laid off into rows from three to four feet apart,<br />

then ridged up by throwing two furrows of a<br />

turning-plow together. A small shovel-plow<br />

made a trench in the ridge to receive the seed.<br />

A man and a mule followed with a “board”<br />

which lightly covered the seed with earth.<br />

When the cotton was up and growing well,<br />

cultivation began by throwing earth to it with a<br />

“cotton sweep,” and the space between the rows<br />

was plowed up and thoroughly pulverized and<br />

the “sweeping” repeated. As soon as the plants<br />

strengthened sufficiently, they were cut out “to<br />

a stand” by a small hoe, spaced from eight to<br />

eighteen inches. The hoe performed a double<br />

duty, for it cut out also the fine grass that sprang<br />

up about the young plants. Plowing and hoeing<br />

now continued as rapidly as possible—taking<br />

into consideration that ten days, at least, must<br />

elapse between each operation—until the<br />

cotton shaded the land sufficiently to protect<br />

itself against the growth of grass, and until the<br />

plow injured the plant by breaking branches.<br />

The cotton was now said to be “laid by.”<br />

After about two months, flower buds called<br />

“squares” appeared on the cotton plants. In<br />

another three weeks, the blossoms opened.<br />

Their petals changed from creamy white, to<br />

yellow, to pink and finally dark red. After<br />

three days, they withered and fell, leaving<br />

green pods called cotton bolls. Inside the boll,<br />

which is shaped like a mini football, moist<br />

fibers formed and pushed the newly formed<br />

seeds outward. As the boll ripened, it stayed<br />

green. The fibers continued to expand under<br />

the warm sun. Finally, they split the boll<br />

apart, and the fluffy cotton came forth. It<br />

looked like cotton candy, only white. Cotton<br />

pickers then went down the rows transferring<br />

the cotton to their bags. After weighing, the<br />

cotton was spread out to be dried and sunned,<br />

then “ginned,” that is, the soft white lint was<br />

separated from the seeds. The “cleaned,” or<br />

“ginned,” cotton was now pressed into bales<br />

ready for the market. The planter marked the<br />

bales with his initials and separated it into<br />

eight grades—”stained,” “tinged,” “ordinary,”<br />

“good ordinary,” “low middling,” “middling,”<br />

“good middling,” and “fancy.” “Stained” and<br />

“tinged” indicated cotton injured by frost. The<br />

remaining grades ranged from those soiled by<br />

dust, leaves, and trash to the “fancy,” which<br />

is the finest of all and perfectly clean. The<br />

seed went to the cotton-seed-oil factories<br />

to be pressed for oil, or converted into<br />

cake for feeding stock or into a material for<br />

making paper.<br />

It was 150 years after the cotton gin before<br />

there was another comparable improvement<br />

in efficiency in the cotton business. In the<br />

1940s mechanized planting and harvesting<br />

began to reduce the number of man hours<br />

required to produce one hundred pounds<br />

of cotton. In 1945, forty-two labor hours<br />

were required. By 1965 that number had<br />

been reduced to five, a reduction of eightyeight<br />

percent. Since then hours required to<br />

produce one hundred pounds of cotton have<br />

declined further.<br />

<strong>Louisiana</strong> is sixth among the states in<br />

average cotton production. Texas is first with<br />

4.56 million bales, followed by California,<br />

Mississippi, Arkansas, and Georgia. Worldwide<br />

production has recently averaged eighty-seven<br />

million bales per year.