N. 46/47 Palomar : voyeur, voyant, visionnaire - ViceVersaMag

N. 46/47 Palomar : voyeur, voyant, visionnaire - ViceVersaMag

N. 46/47 Palomar : voyeur, voyant, visionnaire - ViceVersaMag

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The alphabet probably changed<br />

the way we see the world<br />

phy, grammar, philosophy, physics, geometry,<br />

astronomy, art and architecture.<br />

The alphabet probably changed the way<br />

we see the world. The birth of perspective<br />

between the late 13th century and the late<br />

Renaissance is a perfect example of how the<br />

alphabet may indeed have reprocessed our<br />

mind. Talking to Jonathan Miller, Ernst<br />

Gombrich suggested that the refinement of<br />

perspectivist representation arose from a<br />

demand for realism which he calls the "eyewitness<br />

principle", the desire to represent and<br />

to see an event as if it were happening right<br />

there: "It was this demand which, twice in<br />

FIGURE 2<br />

history (in the ancient world and in the<br />

Renaissance) led to the process we have been<br />

talking about, the imitation of nature through<br />

'schema and correction', through 'making<br />

and matching' by means of a systematic series<br />

of trial and error which allowed us finally to<br />

look across the flat picture surface into an<br />

34 Vlc:EVEkSA« NUMÉRO <strong>46</strong>-17<br />

imaginary world evoked by the artist." 7<br />

However, not every culture has a similar<br />

need to discover perspective. Our culture<br />

only began to develop a taste for perspective<br />

when people first learned to read the alphabet<br />

during the Golden Age of ancient<br />

Greece, and then again around the time<br />

when print was invented by Johannes<br />

Gutenberg. We do not really want or even<br />

need to see things in perspective, unless<br />

something invites us automatically to analyze<br />

the visual field. There is no special need for<br />

the scientific representation of three-dimensional<br />

space to orient ourselves in space.<br />

Many other perceptual properties of the visual<br />

system, even in monocular vision, contribute<br />

to our appreciation of depth-of-field.<br />

We can readily appreciate how our ordinary<br />

binocular vision puts everything "in perspective",<br />

so to speak. It takes two eyes, from two<br />

slightly different points of view, for the brain<br />

to calculate, verify and restore the constancy<br />

of the proportions of space between objects.<br />

I think that it is the practice of the alphabet<br />

which has encouraged our brains to systematically<br />

analyze the visual field.To achieve<br />

perspective, the brain is required to calculate<br />

the relationships and the final product of the<br />

combined visual fields of both eyes. As I<br />

mentioned above, our total visual-field is<br />

covered by four "half-eyes". This is the basis<br />

for the so-called "optic chiasm" (fig. l).The<br />

division of each eye in two parts is critical to<br />

understand the fundamental mechanisms of<br />

vision because, although each part of the<br />

same eye is exposed to approximately the<br />

same area of vision, it dees not see it the same<br />

way. One part of the eye merely "sees" the<br />

area, while the other part analyses it. The<br />

information is the same but it is processed<br />

differently by each hemisphere: the lefthemifield-right-brain<br />

combination provides<br />

the visual material as a whole; the righthemifield-left-brain<br />

combination performs<br />

the analysis of that visual material in its constituent<br />

parts. It is the superimposition of the<br />

visual fields reflected in both retinas which<br />

allows the brain to estimate and generalize<br />

constant proportions'*. The left halves of both<br />

eyes provide the evidence, and the right<br />

halves analyze it.<br />

It is quite possible that the increased participation<br />

of the left hemisphere which is<br />

required for reading, leading to a more<br />

intense collaboration of both sides of the<br />

brain in other cognitive strategies, encouraged<br />

steps towards stereovision. The extra<br />

emphasis brought to spatial perception by<br />

artificial stereovision gives it a magical, almost<br />

surreal quality. It must have been exciting,<br />

almost magical, for people to discover perspective<br />

in the great artworks of the<br />

Renaissance. We can appreciate the pleasure<br />

we can receive from this extra bit of "reality"<br />

with stereoscopes. Stereoscopic vision is a<br />

very demanding kind of vision. It is also quite<br />

difficult to achieve for many people.Try it for<br />

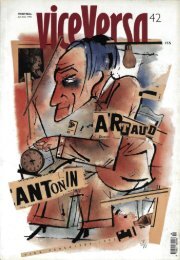

yourself with the help of figure 2. By crossing<br />

your eyes as if you were "making a face", you<br />

must try to bring together the left and the<br />

right squares containing the central icons. If<br />

you succeed, you may be surprised at the<br />

intensity and the quality of the relief given to<br />

that image. Like the process of reading the<br />

alphabet, stereoscopic vision requires the collaboration<br />

of complex interhemispheric<br />

operations.<br />

The alphabet stabilized and regulated the<br />

collaboration of the left and the right hemispheres<br />

to focus man's approach to nature.<br />

Seeing things in perspective also means