Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

• We categorize: We find it useful to put people, ourselves included, into categories.<br />

To label someone as a Hindu, a Scot, or a bus driver is a shorthand way<br />

of saying some other things about the person.<br />

• We identify: We associate ourselves with certain groups (our ingroups ) and<br />

gain self-esteem by doing so.<br />

• We compare: We contrast our groups with other groups ( outgroups ), with a<br />

favorable bias toward our own group.<br />

We humans naturally divide others into those inside and those outside our<br />

group. We also evaluate ourselves partly by our group memberships. Having a<br />

sense of “we-ness” strengthens our self-concepts. It feels good. We seek not only<br />

respect for ourselves but also pride in our groups (Smith & Tyler, 1997). Moreover,<br />

seeing our groups as superior helps us feel even better. It’s as if we all think, “I am<br />

an X [name your group]. X is good. Therefore, I am good.”<br />

Lacking a positive personal identity, people often seek self-esteem by identifying<br />

with a group. Thus, many disadvantaged youths find pride, power, security, and<br />

identity in gang affiliations. When people’s personal and social identities become<br />

fused—when the boundary between self and group blurs—they become more<br />

willing to fight or die for their group (Gómez & others, 2011; Swann & others, 2009).<br />

Many superpatriots, for example, define themselves by their national identities<br />

(Staub, 1997, 2005). And many people at loose ends find identity in their associations<br />

with new religious movements, self-help groups, or fraternal clubs ( Figure 9.4 ).<br />

Because of our social identifications, we conform to our group norms. We sacrifice<br />

ourselves for team, family, nation. And the more important our social identity<br />

and the more strongly attached we feel to a group, the more we react prejudicially<br />

to threats from another group (Crocker & Luhtanen, 1990; Hinkle & others, 1992).<br />

INGROUP BIAS<br />

The group definition of who you are—your gender, race, religion, marital status,<br />

academic major—implies a definition of who you are not. The circle that includes<br />

“us” (the ingroup) excludes “them” (the outgroup). The more that ethnic Turks<br />

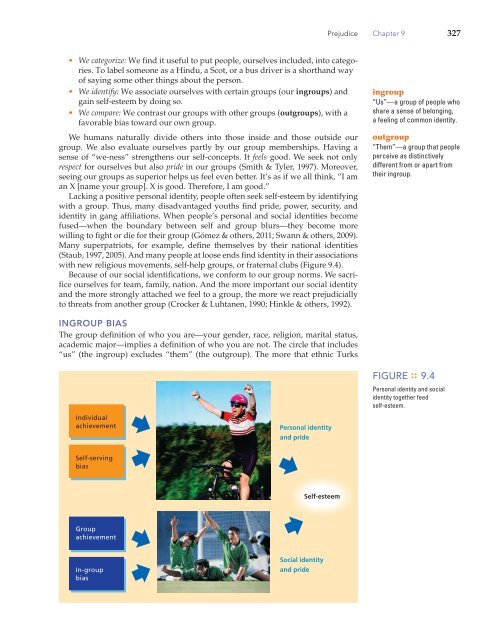

Individual<br />

achievement<br />

Self-serving<br />

bias<br />

Group<br />

achievement<br />

In-group<br />

bias<br />

Personal identity<br />

and pride<br />

Self-esteem<br />

Social identity<br />

and pride<br />

<strong>Prejudice</strong> <strong>Chapter</strong> 9 327<br />

ingroup<br />

“Us”—a group of people who<br />

share a sense of belonging,<br />

a feeling of common identity.<br />

outgroup<br />

“Them”—a group that people<br />

perceive as distinctively<br />

different from or apart from<br />

their ingroup.<br />

FIGURE :: 9.4<br />

Personal identity and social<br />

identity together feed<br />

self-esteem.