Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

344 Part Three Social Relations<br />

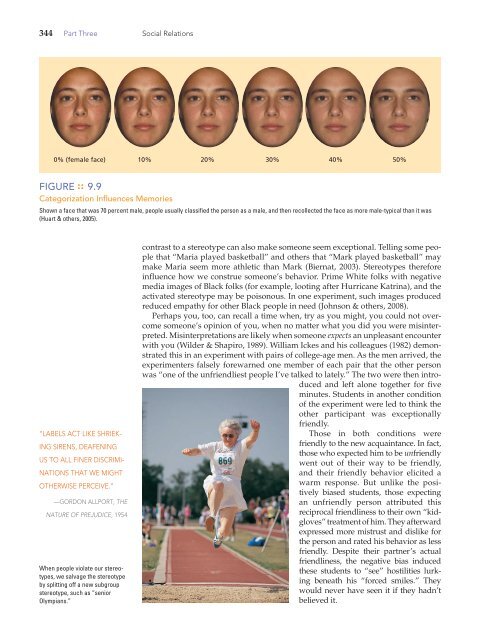

0% (female face) 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%<br />

FIGURE :: 9.9<br />

Categorization Influences Memories<br />

Shown a face that was 70 percent male, people usually classified the person as a male, and then recollected the face as more male-typical than it was<br />

(Huart & others, 2005).<br />

“LABELS ACT LIKE SHRIEK-<br />

ING SIRENS, DEAFENING<br />

US TO ALL FINER DISCRIMI-<br />

NATIONS THAT WE MIGHT<br />

OTHERWISE PERCEIVE.”<br />

—GORDON ALLPORT, THE<br />

NATURE OF PREJUDICE, 1954<br />

When people violate our stereotypes,<br />

we salvage the stereotype<br />

by splitting off a new subgroup<br />

stereotype, such as “senior<br />

Olympians.”<br />

contrast to a stereotype can also make someone seem exceptional. Telling some people<br />

that “Maria played basketball” and others that “Mark played basketball” may<br />

make Maria seem more athletic than Mark (Biernat, 2003). Stereotypes therefore<br />

influence how we construe someone’s behavior. Prime White folks with negative<br />

media images of Black folks (for example, looting after Hurricane Katrina), and the<br />

activated stereotype may be poisonous. In one experiment, such images produced<br />

reduced empathy for other Black people in need (Johnson & others, 2008).<br />

Perhaps you, too, can recall a time when, try as you might, you could not overcome<br />

someone’s opinion of you, when no matter what you did you were misinterpreted.<br />

Misinterpretations are likely when someone expects an unpleasant encounter<br />

with you (Wilder & Shapiro, 1989). William Ickes and his colleagues (1982) demonstrated<br />

this in an experiment with pairs of college-age men. As the men arrived, the<br />

experimenters falsely forewarned one member of each pair that the other person<br />

was “one of the unfriendliest people I’ve talked to lately.” The two were then introduced<br />

and left alone together for five<br />

minutes. Students in another condition<br />

of the experiment were led to think the<br />

other participant was exceptionally<br />

friendly.<br />

Those in both conditions were<br />

friendly to the new acquaintance. In fact,<br />

those who expected him to be un friendly<br />

went out of their way to be friendly,<br />

and their friendly behavior elicited a<br />

warm response. But unlike the positively<br />

biased students, those expecting<br />

an unfriendly person attributed this<br />

reciprocal friendliness to their own “kidgloves”<br />

treatment of him. They afterward<br />

expressed more mistrust and dislike for<br />

the person and rated his behavior as less<br />

friendly. Despite their partner’s actual<br />

friendliness, the negative bias induced<br />

these students to “see” hostilities lurking<br />

beneath his “forced smiles.” They<br />

would never have seen it if they hadn’t<br />

believed it.