Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

questions, they apparently felt added apprehension, which undermined their performances.<br />

For female engineering students, interacting with a sexist man likewise<br />

undermines test performance (Logel & others, 2009). Even before exams, stereotype<br />

threat can also hamper women’s learning math rules and operations (Rydell &<br />

others, 2010).<br />

The media can provoke stereotype threat. Paul Davies and his colleagues (2002,<br />

2005) had women and men watch a series of commercials while expecting that<br />

they would be tested for their memory of details. For half the participants, the<br />

commercials contained only neutral stimuli; for the other half, some of the commercials<br />

contained images of “airheaded” women. After seeing the stereotypic<br />

images, women not only performed worse than men on a math test but also<br />

reported less interest in obtaining a math or science major or entering a math or<br />

science career.<br />

Might racial stereotypes be similarly self-fulfilling? Steele and Joshua Aronson<br />

(1995) gave difficult verbal abilities tests to Whites and Blacks. Blacks underperformed<br />

Whites only when taking the tests under conditions high in stereotype<br />

threat. A similar stereotype threat effect has occurred with Hispanic Americans<br />

(Nadler & Clark, 2011).<br />

Jeff Stone and his colleagues (1999) report that stereotype threat affects athletic<br />

performance, too. Blacks did worse than usual when a golf task was framed as a<br />

test of “sports intelligence,” and Whites did worse when it was a test of “natural<br />

athletic ability.” “When people are reminded of a negative stereotype about themselves—‘White<br />

men can’t jump’ or ‘Black men can’t think’—it can adversely affect<br />

performance,” Stone (2000) surmised.<br />

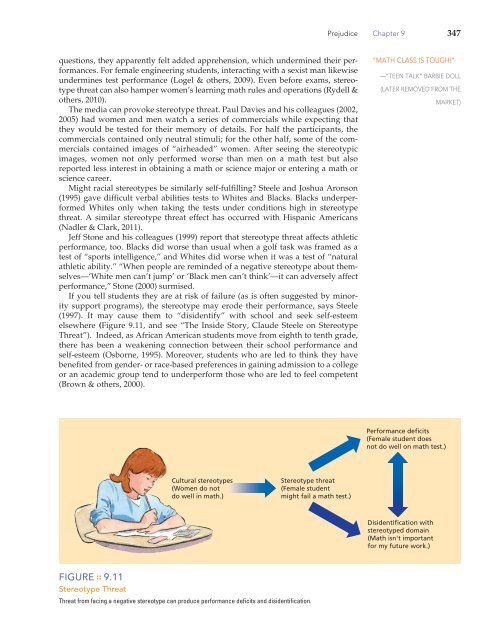

If you tell students they are at risk of failure (as is often suggested by minority<br />

support programs), the stereotype may erode their performance, says Steele<br />

(1997). It may cause them to “disidentify” with school and seek self-esteem<br />

elsewhere ( Figure 9.11 , and see “The Inside Story, Claude Steele on Stereotype<br />

Threat”). Indeed, as African American students move from eighth to tenth grade,<br />

there has been a weakening connection between their school performance and<br />

self-esteem (Osborne, 1995). Moreover, students who are led to think they have<br />

benefited from gender- or race-based preferences in gaining admission to a college<br />

or an academic group tend to underperform those who are led to feel competent<br />

(Brown & others, 2000).<br />

FIGURE :: 9.11<br />

Stereotype Threat<br />

Cultural stereotypes<br />

(Women do not<br />

do well in math.)<br />

Threat from facing a negative stereotype can produce performance deficits and disidentification.<br />

Stereotype threat<br />

(Female student<br />

might fail a math test.)<br />

<strong>Prejudice</strong> <strong>Chapter</strong> 9 347<br />

“MATH CLASS IS TOUGH!”<br />

—“TEEN TALK” BARBIE DOLL<br />

(LATER REMOVED FROM THE<br />

Performance deficits<br />

(Female student does<br />

not do well on math test.)<br />

Disidentification with<br />

stereotyped domain<br />

(Math isn't important<br />

for my future work.)<br />

MARKET)