Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

correlations in people’s minds (Risen & others, 2007). This enables the mass media<br />

to feed illusory correlations. When a self-described homosexual person murders or<br />

sexually abuses someone, homosexuality is often mentioned. When a heterosexual<br />

does the same, the person’s sexual orientation is seldom mentioned. Likewise,<br />

when ex-mental patients Mark Chapman and John Hinckley, Jr., shot John Lennon<br />

and President Reagan, respectively, the assailants’ mental histories commanded<br />

attention. Assassins and mental hospitalization are both relatively infrequent, making<br />

the combination especially newsworthy. Such reporting adds to the illusion of<br />

a large correlation between (1) violent tendencies and (2) homosexuality or mental<br />

hospitalization.<br />

Unlike the students who judged Groups A and B, we often have preexisting<br />

biases. David Hamilton’s further research with Terrence Rose (1980) revealed that<br />

our preexisting stereotypes can lead us to “see” correlations that aren’t there. The<br />

researchers had University of California at Santa Barbara students read sentences in<br />

which various adjectives described the members of different occupational groups<br />

(“Juan, an accountant, is timid and thoughtful”). In actuality, each occupation was<br />

described equally often by each adjective; accountants, doctors, and salespeople<br />

were equally often timid, wealthy, and talkative. The students, however, thought<br />

they had more often read descriptions of timid accountants, wealthy doctors, and<br />

talkative salespeople. Their stereotyping led them to perceive correlations that<br />

weren’t there, thus helping to perpetuate the stereotypes.<br />

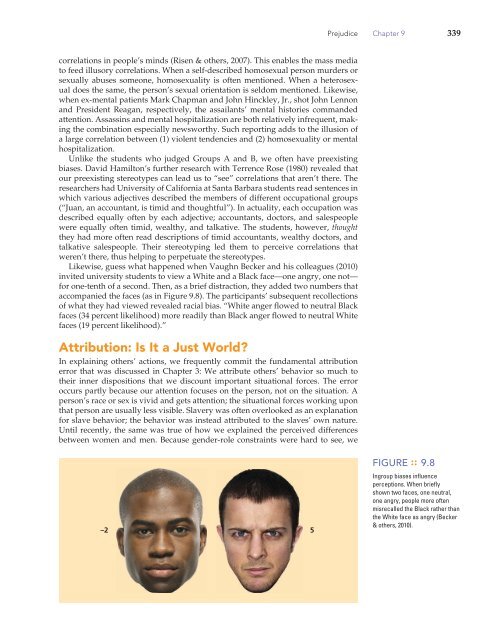

Likewise, guess what happened when Vaughn Becker and his colleagues (2010)<br />

invited university students to view a White and a Black face—one angry, one not—<br />

for one-tenth of a second. Then, as a brief distraction, they added two numbers that<br />

accompanied the faces (as in Figure 9.8 ). The participants’ subsequent recollections<br />

of what they had viewed revealed racial bias. “White anger flowed to neutral Black<br />

faces (34 percent likelihood) more readily than Black anger flowed to neutral White<br />

faces (19 percent likelihood).”<br />

Attribution: Is It a Just World?<br />

In explaining others’ actions, we frequently commit the fundamental attribution<br />

error that was discussed in <strong>Chapter</strong> 3: We attribute others’ behavior so much to<br />

their inner dispositions that we discount important situational forces. The error<br />

occurs partly because our attention focuses on the person, not on the situation. A<br />

person’s race or sex is vivid and gets attention; the situational forces working upon<br />

that person are usually less visible. Slavery was often overlooked as an explanation<br />

for slave behavior; the behavior was instead attributed to the slaves’ own nature.<br />

Until recently, the same was true of how we explained the perceived differences<br />

between women and men. Because gender-role constraints were hard to see, we<br />

–2 5<br />

<strong>Prejudice</strong> <strong>Chapter</strong> 9 339<br />

FIGURE :: 9.8<br />

Ingroup biases influence<br />

perceptions. When briefly<br />

shown two faces, one neutral,<br />

one angry, people more often<br />

misrecalled the Black rather than<br />

the White face as angry (Becker<br />

& others, 2010).