Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

346 Part Three Social Relations<br />

“IF WE FORESEE EVIL IN<br />

OUR FELLOW MAN, WE<br />

TEND TO PROVOKE IT; IF<br />

GOOD, WE ELICIT IT.”<br />

—GORDON ALLPORT, THE<br />

NATURE OF PREJUDICE, 1958<br />

stereotype threat<br />

A disruptive concern,<br />

when facing a negative<br />

stereotype, that one will<br />

be evaluated based on a<br />

negative stereotype. Unlike<br />

self-fulfilling prophecies that<br />

hammer one’s reputation<br />

into one’s self-concept,<br />

stereotype threat situations<br />

have immediate effects.<br />

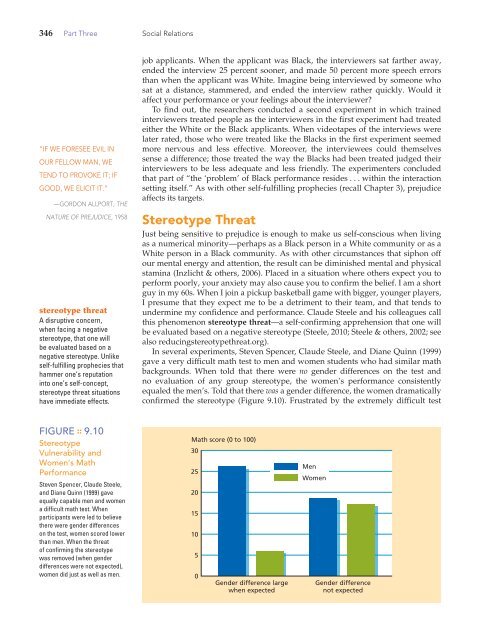

FIGURE :: 9.10<br />

Stereotype<br />

Vulnerability and<br />

Women’s Math<br />

Performance<br />

Steven Spencer, Claude Steele,<br />

and Diane Quinn (1999) gave<br />

equally capable men and women<br />

a difficult math test. When<br />

participants were led to believe<br />

there were gender differences<br />

on the test, women scored lower<br />

than men. When the threat<br />

of confirming the stereotype<br />

was removed (when gender<br />

differences were not expected),<br />

women did just as well as men.<br />

job applicants. When the applicant was Black, the interviewers sat farther away,<br />

ended the interview 25 percent sooner, and made 50 percent more speech errors<br />

than when the applicant was White. Imagine being interviewed by someone who<br />

sat at a distance, stammered, and ended the interview rather quickly. Would it<br />

affect your performance or your feelings about the interviewer?<br />

To find out, the researchers conducted a second experiment in which trained<br />

interviewers treated people as the interviewers in the first experiment had treated<br />

either the White or the Black applicants. When videotapes of the interviews were<br />

later rated, those who were treated like the Blacks in the first experiment seemed<br />

more nervous and less effective. Moreover, the interviewees could themselves<br />

sense a difference; those treated the way the Blacks had been treated judged their<br />

interviewers to be less adequate and less friendly. The experimenters concluded<br />

that part of “the ‘problem’ of Black performance resides . . . within the interaction<br />

setting itself.” As with other self-fulfilling prophecies (recall <strong>Chapter</strong> 3), prejudice<br />

affects its targets.<br />

Stereotype Threat<br />

Just being sensitive to prejudice is enough to make us self-conscious when living<br />

as a numerical minority—perhaps as a Black person in a White community or as a<br />

White person in a Black community. As with other circumstances that siphon off<br />

our mental energy and attention, the result can be diminished mental and physical<br />

stamina (Inzlicht & others, 2006). Placed in a situation where others expect you to<br />

perform poorly, your anxiety may also cause you to confirm the belief. I am a short<br />

guy in my 60s. When I join a pickup basketball game with bigger, younger players,<br />

I presume that they expect me to be a detriment to their team, and that tends to<br />

undermine my confidence and performance. Claude Steele and his colleagues call<br />

this phenomenon stereotype threat —a self-confirming apprehension that one will<br />

be evaluated based on a negative stereotype (Steele, 2010; Steele & others, 2002; see<br />

also reducingstereotypethreat.org ).<br />

In several experiments, Steven Spencer, Claude Steele, and Diane Quinn (1999)<br />

gave a very difficult math test to men and women students who had similar math<br />

backgrounds. When told that there were no gender differences on the test and<br />

no evaluation of any group stereotype, the women’s performance consistently<br />

equaled the men’s. Told that there was a gender difference, the women dramatically<br />

confirmed the stereotype ( Figure 9.10 ). Frustrated by the extremely difficult test<br />

Math score (0 to 100)<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Gender difference large<br />

when expected<br />

Men<br />

Women<br />

Gender difference<br />

not expected