Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

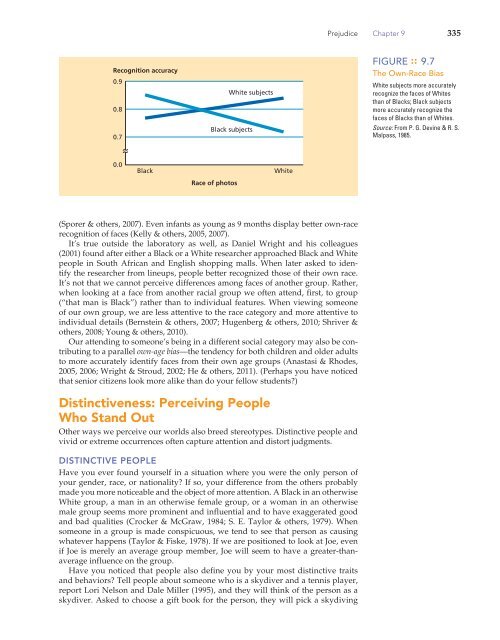

Recognition accuracy<br />

0.9<br />

0.8<br />

0.7<br />

0.0<br />

Black<br />

Race of photos<br />

White subjects<br />

Black subjects<br />

White<br />

(Sporer & others, 2007). Even infants as young as 9 months display better own-race<br />

recognition of faces (Kelly & others, 2005, 2007).<br />

It’s true outside the laboratory as well, as Daniel Wright and his colleagues<br />

(2001) found after either a Black or a White researcher approached Black and White<br />

people in South African and English shopping malls. When later asked to identify<br />

the researcher from lineups, people better recognized those of their own race.<br />

It’s not that we cannot perceive differences among faces of another group. Rather,<br />

when looking at a face from another racial group we often attend, first, to group<br />

(“that man is Black”) rather than to individual features. When viewing someone<br />

of our own group, we are less attentive to the race category and more attentive to<br />

individual details (Bernstein & others, 2007; Hugenberg & others, 2010; Shriver &<br />

others, 2008; Young & others, 2010).<br />

Our attending to someone’s being in a different social category may also be contributing<br />

to a parallel own-age bias —the tendency for both children and older adults<br />

to more accurately identify faces from their own age groups (Anastasi & Rhodes,<br />

2005, 2006; Wright & Stroud, 2002; He & others, 2011). (Perhaps you have noticed<br />

that senior citizens look more alike than do your fellow students?)<br />

Distinctiveness: Perceiving People<br />

Who Stand Out<br />

Other ways we perceive our worlds also breed stereotypes. Distinctive people and<br />

vivid or extreme occurrences often capture attention and distort judgments.<br />

DISTINCTIVE PEOPLE<br />

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you were the only person of<br />

your gender, race, or nationality? If so, your difference from the others probably<br />

made you more noticeable and the object of more attention. A Black in an otherwise<br />

White group, a man in an otherwise female group, or a woman in an otherwise<br />

male group seems more prominent and influential and to have exaggerated good<br />

and bad qualities (Crocker & McGraw, 1984; S. E. Taylor & others, 1979). When<br />

someone in a group is made conspicuous, we tend to see that person as causing<br />

whatever happens (Taylor & Fiske, 1978). If we are positioned to look at Joe, even<br />

if Joe is merely an average group member, Joe will seem to have a greater- thanaverage<br />

influence on the group.<br />

Have you noticed that people also define you by your most distinctive traits<br />

and behaviors? Tell people about someone who is a skydiver and a tennis player,<br />

report Lori Nelson and Dale Miller (1995), and they will think of the person as a<br />

skydiver. Asked to choose a gift book for the person, they will pick a skydiving<br />

<strong>Prejudice</strong> <strong>Chapter</strong> 9 335<br />

FIGURE :: 9.7<br />

The Own-Race Bias<br />

White subjects more accurately<br />

recognize the faces of Whites<br />

than of Blacks; Black subjects<br />

more accurately recognize the<br />

faces of Blacks than of Whites.<br />

Source: From P. G. Devine & R. S.<br />

Malpass, 1985.