Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Chapter 9: Prejudice: Disliking Others (2947.0K) - Bad Request

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Prejudice</strong> <strong>Chapter</strong> 9 345<br />

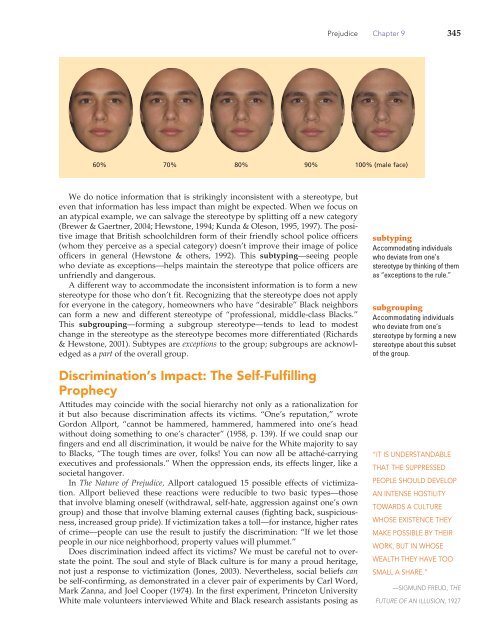

60% 70% 80% 90% 100% (male face)<br />

We do notice information that is strikingly inconsistent with a stereotype, but<br />

even that information has less impact than might be expected. When we focus on<br />

an atypical example, we can salvage the stereotype by splitting off a new category<br />

(Brewer & Gaertner, 2004; Hewstone, 1994; Kunda & Oleson, 1995, 1997). The positive<br />

image that British schoolchildren form of their friendly school police officers<br />

(whom they perceive as a special category) doesn’t improve their image of police<br />

officers in general (Hewstone & others, 1992). This subtyping —seeing people<br />

who deviate as exceptions—helps maintain the stereotype that police officers are<br />

unfriendly and dangerous.<br />

A different way to accommodate the inconsistent information is to form a new<br />

stereotype for those who don’t fit. Recognizing that the stereotype does not apply<br />

for everyone in the category, homeowners who have “desirable” Black neighbors<br />

can form a new and different stereotype of “professional, middle-class Blacks.”<br />

This subgrouping —forming a subgroup stereotype—tends to lead to modest<br />

change in the stereotype as the stereotype becomes more differentiated (Richards<br />

& Hewstone, 2001). Subtypes are exceptions to the group; subgroups are acknowledged<br />

as a part of the overall group.<br />

Discrimination’s Impact: The Self-Fulfilling<br />

Prophecy<br />

Attitudes may coincide with the social hierarchy not only as a rationalization for<br />

it but also because discrimination affects its victims. “One’s reputation,” wrote<br />

Gordon Allport, “cannot be hammered, hammered, hammered into one’s head<br />

without doing something to one’s character” (1958, p. 139). If we could snap our<br />

fingers and end all discrimination, it would be naive for the White majority to say<br />

to Blacks, “The tough times are over, folks! You can now all be attaché-carrying<br />

executives and professionals.” When the oppression ends, its effects linger, like a<br />

societal hangover.<br />

In The Nature of <strong>Prejudice</strong>, Allport catalogued 15 possible effects of victimization.<br />

Allport believed these reactions were reducible to two basic types—those<br />

that involve blaming oneself (withdrawal, self-hate, aggression against one’s own<br />

group) and those that involve blaming external causes (fighting back, suspiciousness,<br />

increased group pride). If victimization takes a toll—for instance, higher rates<br />

of crime—people can use the result to justify the discrimination: “If we let those<br />

people in our nice neighborhood, property values will plummet.”<br />

Does discrimination indeed affect its victims? We must be careful not to overstate<br />

the point. The soul and style of Black culture is for many a proud heritage,<br />

not just a response to victimization (Jones, 2003). Nevertheless, social beliefs can<br />

be self-confirming, as demonstrated in a clever pair of experiments by Carl Word,<br />

Mark Zanna, and Joel Cooper (1974). In the first experiment, Princeton University<br />

White male volunteers interviewed White and Black research assistants posing as<br />

subtyping<br />

Accommodating individuals<br />

who deviate from one’s<br />

stereotype by thinking of them<br />

as “exceptions to the rule.”<br />

subgrouping<br />

Accommodating individuals<br />

who deviate from one’s<br />

stereotype by forming a new<br />

stereotype about this subset<br />

of the group.<br />

“IT IS UNDERSTANDABLE<br />

THAT THE SUPPRESSED<br />

PEOPLE SHOULD DEVELOP<br />

AN INTENSE HOSTILITY<br />

TOWARDS A CULTURE<br />

WHOSE EXISTENCE THEY<br />

MAKE POSSIBLE BY THEIR<br />

WORK, BUT IN WHOSE<br />

WEALTH THEY HAVE TOO<br />

SMALL A SHARE.”<br />

—SIGMUND FREUD, THE<br />

FUTURE OF AN ILLUSION, 1927