Architecture and Modernity : A Critique

Architecture and Modernity : A Critique

Architecture and Modernity : A Critique

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

132<br />

According to Tafuri, the most<br />

pressing question was the reconciliation<br />

of these two attitudes. Not only<br />

was it a vital problem for constructivism<br />

<strong>and</strong> for the urban development<br />

projects of the Social Democrat municipal<br />

authorities in the Weimar Republic;<br />

he also sees it as pivotal in the<br />

work of Walter Benjamin in the thirties.<br />

Tafuri argues that Benjamin’s thesis<br />

about the “decay of the aura” in<br />

his work of art essay should be interpreted<br />

not only as a comment on the<br />

universal adoption of new methods of<br />

production, but also as the statement<br />

of a deliberate choice: to reject the sacred<br />

character of artistic work, <strong>and</strong><br />

thus to accept its destruction.<br />

The opposite choice, however,<br />

of attempting to preserve the autonomy<br />

of intellectual work, also responds<br />

to a quite specific need within capitalist development—the need, that is, to<br />

recover the notion of “Subjectivity” (the capital S is Tafuri’s) that had become alienated<br />

by the division of labor. This, however, merely constitutes a rearguard action: the<br />

“disappearance of the subject” is historically inevitable due to the advance of capitalist<br />

rationalization. Every attempt to halt this development is, by definition, doomed<br />

to failure, according to Tafuri. And yet these “subjectivist” attempts have a specific<br />

purpose in terms of capitalist evolution in that they perform the task of providing a<br />

kind of comfort. In this sense too, Tafuri argues, a stance of this sort serves to prop<br />

up the system.<br />

Tafuri considers that the constructive <strong>and</strong> destructive movements within the<br />

entire avant-garde movement are only seemingly opposed. They are both responses<br />

to the empirical everyday reality of the capitalist way of life; the former rejects it with<br />

a view to creating a new order, the latter responds by exalting the chaotic character<br />

of reality. The constructive tendencies “opposed Chaos, the empirical <strong>and</strong> the commonplace,<br />

with the principle of Form.” 152 This “Form” originated in the inner laws of<br />

industrial production <strong>and</strong> was thus compatible with the underlying logic that gave this<br />

apparent chaos its structure. It is here that the significance of a movement like De<br />

Stijl is to be found: “The ‘De Stijl’ technique of decomposition of complex into elementary<br />

forms corresponded to the discovery that the ‘new richness’ of spirit could<br />

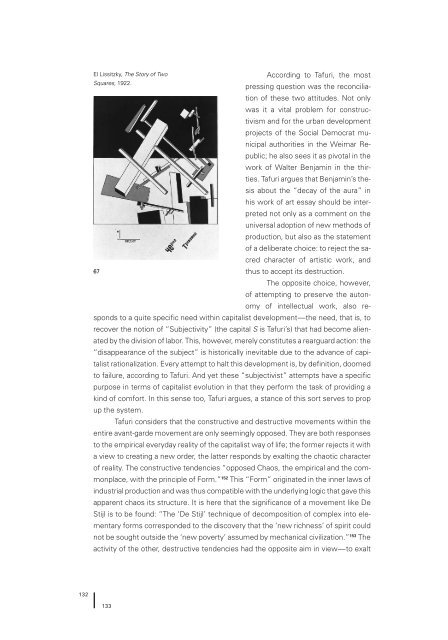

not be sought outside the ‘new poverty’ assumed by mechanical civilization.” 153 El Lissitzky, The Story of Two<br />

Squares, 1922.<br />

67<br />

The<br />

activity of the other, destructive tendencies had the opposite aim in view—to exalt<br />

133