DOLOMITES - Annexes 2-8 - Provincia di Udine

DOLOMITES - Annexes 2-8 - Provincia di Udine

DOLOMITES - Annexes 2-8 - Provincia di Udine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

NOMINATION OF THE <strong>DOLOMITES</strong> FOR INSCRIPTION ON THE WORLD NATURAL HERITAGE LIST UNESCO<br />

99<br />

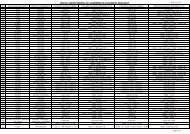

origins of the Dolomite fauna<br />

Following the criteria of a recent analysis of the fauna that can be recognized in the animal population<br />

of the entire Alpine chain (Chemini and Vigna Taglianti 2002), we can see six <strong>di</strong>stinct groups<br />

represented of Dolomite fauna.<br />

Species endemic to the Alps.<br />

While the southern edge of the Alps plays host, especially in the area of cave-dwelling fauna, to several<br />

species of very specifically localized <strong>di</strong>stribution whose origins can be traced back to antiquity,<br />

this component is lacking in the innermost belt of the Alpine chain due to the severity of the weather<br />

con<strong>di</strong>tions that it was subjected to during the Pleistocene age. Here, we find several localized (endemic)<br />

species of a more recent origin. This category includes species exclusive to the Alpine chain or<br />

a portion of it, which subsist mainly in the me<strong>di</strong>um to higher elevations and which have originated<br />

by geographic isolation with respect to similar species that remained allocated in other mountain regions<br />

of Eurasia, between the end of the Pliocene and the Pleistocene eras. Among the vertebrates,<br />

this fauna sector in the Dolomites is represented by the black salamander (S. atra), but the invertebrates<br />

are even more numerous. Among these, several species of ground beetles of the Carabus genus,<br />

such as C. (Orinocarabus) adamellicola, C. (O.) alpestris dolomitanus and C. (Orinocarabus) bertolinii.<br />

These belong to a group of species whose <strong>di</strong>stribution areas, complex and partly overlapping, are the<br />

result of complicated paleogeographic and paleoclimatic events that involved the fauna of the high<br />

Alpine elevations. Numerous other species of beetles are found in geographic areas of the same type,<br />

for example, in the genera of Nebria, Trechus, Simplocaria, Dichotrachelus, Otiorhynchus and Oreina.<br />

Glacial relicts of the massifs de réfuge.<br />

Even during the coldest glacial phases of the Quaternary era, the Alpine and Prealpine regions had<br />

never been completely covered with glaciers. Here, there were areas that acted as “refuge massifs”<br />

where several animal (and plant) populations that were better able to withstand the harshness of the<br />

weather con<strong>di</strong>tions managed to survive. The isolation experienced by these populations, even for<br />

short periods of time – on a geological scale - has often led to their <strong>di</strong>fferentiation on a sub-specific<br />

or specific level. This is proven today by the existence of species of a very narrow <strong>di</strong>stribution which<br />

still live in these refugia. These species are represented mainly in the Prealps belt, but are also found<br />

in the southernmost limit of the Dolomites.<br />

Boreoalpine species.<br />

The characteristic present-day fragmented and even punctiform geographic <strong>di</strong>stribution of the species<br />

referred to in this group of fauna is the result of the glaciers pulling back at the end of the last<br />

glacial age, which took place between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago. The previous advancement of<br />

the glaciers southward pushed the animal (and plant) life toward more southern latitudes, where other<br />

natural geographic barriers stopped the flow. For many species, the peninsula of Italy - as in the<br />

other great Me<strong>di</strong>terranean peninsulas - represented a refuge where they were able to survive during<br />

the glacial maximum periods and which became a new starting point in their subsequent colonization<br />

of Central and Northern Europe. The prevalent parallel orientation of the Alps represented a<br />

formidable obstacle to the recolonization which carried northward numerous species surviving the<br />

glacial maximum periods. Several populations remained at the higher elevations in these mountains.<br />

In some cases, migration would begin in one southern refuge area and split along the way, giving<br />

rise to population settlements in the Alps, inclu<strong>di</strong>ng the Dolomites, above the upper limit of the<br />

treeline, and at the same time, to populations that continued their advancement toward Scan<strong>di</strong>navia,<br />

but without making any stable colonies in Central Europe. These were species well adapted to<br />

life in the colder climates (periglacial and similar), whose <strong>di</strong>stributional range is split into two parts,<br />

separated by an enormous <strong>di</strong>stance. The first is a northern area, generally circumscribed to one part