Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Stabler - Lx 185/209 2003<br />

16.2 C<strong>on</strong>textual influences<br />

This is obvious with the various pr<strong>on</strong>ouns and tense markings found in human languages. A standard way to<br />

deal with this is found in Tarski’s famous and readable treatment <strong>of</strong> expressi<strong>on</strong>s like p(X) in first order logic<br />

(Tarski, 1935), and now in almost every introductory logic text. The basic idea is to think <strong>of</strong> each (declarative)<br />

sentence itself as having a value which is a functi<strong>on</strong> from c<strong>on</strong>texts to truth values.<br />

We will postp<strong>on</strong>e the discussi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>on</strong>ouns and tenses, but we can extend the basic idea <strong>of</strong> distinguishing<br />

the linguistic and n<strong>on</strong>-linguistic comp<strong>on</strong>ents <strong>of</strong> the problem to a broad range <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>textual influences. For<br />

example, if in a typical situati<strong>on</strong> I say George charge -s, I may expect you to understand a particular individual<br />

by George, and I may expect you to figure out something about what I mean by charge. For example, George<br />

could be a horse, and by charge I may mean run toward you. Or George could be a grocer, and I may mean that<br />

he makes you pay for your food. This kind <strong>of</strong> making sense <strong>of</strong> what an utterance means is clearly something<br />

that goes <strong>on</strong> when we understand fluent language, but it is regarded as n<strong>on</strong>-linguistic because the process<br />

apparently involves general, n<strong>on</strong>-linguistic knowledge about the situati<strong>on</strong>. Similarly deciding what the prepositi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

phrases attach to in sentences like the following clearly depends <strong>on</strong> your knowledge <strong>of</strong> what I am likely<br />

to be saying, what kinds <strong>of</strong> nouns name comm<strong>on</strong> currencies, etc.<br />

I bought the lock with the keys I bought the lock with my last dollar<br />

I drove down the street in my car I drove down the street with the new asphalt<br />

The decisi<strong>on</strong>s we make here are presumably n<strong>on</strong>-linguistic too.<br />

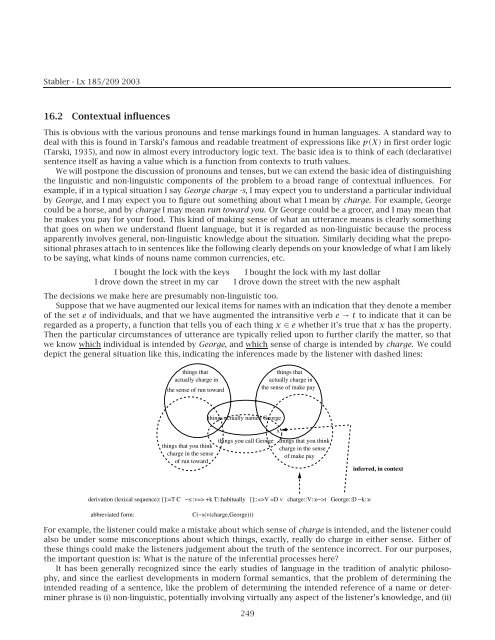

Suppose that we have augmented our lexical items for names with an indicati<strong>on</strong> that they denote a member<br />

<strong>of</strong> the set e <strong>of</strong> individuals, and that we have augmented the intransitive verb e → t to indicate that it can be<br />

regarded as a property, a functi<strong>on</strong> that tells you <strong>of</strong> each thing x ∈ e whether it’s true that x has the property.<br />

Then the particular circumstances <strong>of</strong> utterance are typically relied up<strong>on</strong> to further clarify the matter, so that<br />

we know which individual is intended by George, andwhichsense <strong>of</strong> charge is intended by charge. Wecould<br />

depict the general situati<strong>on</strong> like this, indicating the inferences made by the listener with dashed lines:<br />

things that<br />

actually charge in<br />

the sense <strong>of</strong> run toward<br />

things that you think<br />

charge in the sense<br />

<strong>of</strong> run toward<br />

things actually named George<br />

things you call George<br />

derivati<strong>on</strong> (lexical sequence): []:=T C −s::v=> +k T::habitually []::=>V =D v charge::V::e−>t George::D −k::e<br />

abbreviated form: C(−s(v(charge,George)))<br />

things that<br />

actually charge in<br />

the sense <strong>of</strong> make pay<br />

x<br />

things that you think<br />

charge in the sense<br />

<strong>of</strong> make pay<br />

inferred, in c<strong>on</strong>text<br />

For example, the listener could make a mistake about which sense <strong>of</strong> charge is intended, and the listener could<br />

also be under some misc<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s about which things, exactly, really do charge in either sense. Either <strong>of</strong><br />

these things could make the listeners judgement about the truth <strong>of</strong> the sentence incorrect. For our purposes,<br />

the important questi<strong>on</strong> is: What is the nature <strong>of</strong> the inferential processes here?<br />

It has been generally recognized since the early studies <strong>of</strong> language in the traditi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> analytic philosophy,<br />

and since the earliest developments in modern formal semantics, that the problem <strong>of</strong> determining the<br />

intended reading <strong>of</strong> a sentence, like the problem <strong>of</strong> determining the intended reference <strong>of</strong> a name or determiner<br />

phrase is (i) n<strong>on</strong>-linguistic, potentially involving virtually any aspect <strong>of</strong> the listener’s knowledge, and (ii)<br />

249