Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Stabler - Lx 185/209 2003<br />

16.5 Inference<br />

16.5.1 Reas<strong>on</strong>ing is shallow<br />

It is <strong>of</strong>ten pointed out that comm<strong>on</strong>sense reas<strong>on</strong>ing is “robust” and tends to be shallow and in need <strong>of</strong> support<br />

from multiple sources, while scientific and logical inference is “delicate” and relies <strong>on</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g chains <strong>of</strong> reas<strong>on</strong>ing<br />

with very few points <strong>of</strong> support. Minsky (1988, pp193,189) puts the matter this way:<br />

That theory is worthless. It isn’t even wr<strong>on</strong>g! – Wolfgang Pauli<br />

As scientists we like to make our theories as delicate and fragile as possible. We like to arrange<br />

things so that if the slightest thing goes wr<strong>on</strong>g, everything will collapse at <strong>on</strong>ce!…<br />

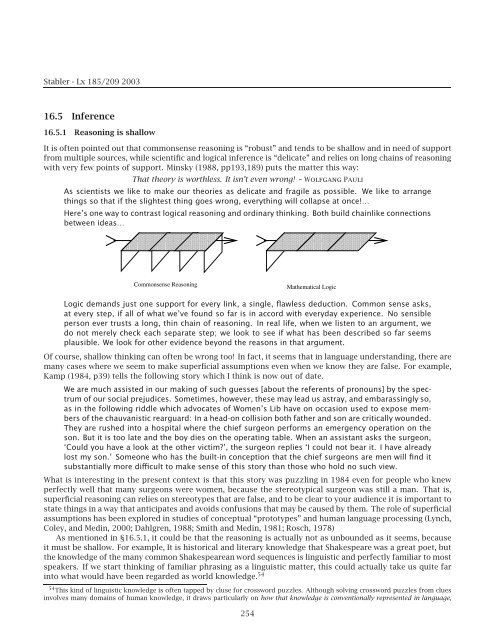

Here’s <strong>on</strong>e way to c<strong>on</strong>trast logical reas<strong>on</strong>ing and ordinary thinking. Both build chainlike c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

between ideas…<br />

000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111<br />

000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111<br />

000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111<br />

000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111<br />

000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111 000000<br />

111111<br />

Comm<strong>on</strong>sense Reas<strong>on</strong>ing<br />

000000<br />

111111 0000000<br />

1111111 0000000<br />

1111111<br />

000000<br />

111111 0000000<br />

1111111 0000000<br />

1111111<br />

000000<br />

111111 0000000<br />

1111111 0000000<br />

1111111<br />

000000<br />

111111 0000000<br />

1111111 0000000<br />

1111111<br />

000000<br />

111111 0000000<br />

1111111 0000000<br />

1111111<br />

Mathematical Logic<br />

Logic demands just <strong>on</strong>e support for every link, a single, flawless deducti<strong>on</strong>. Comm<strong>on</strong> sense asks,<br />

at every step, if all <strong>of</strong> what we’ve found so far is in accord with everyday experience. No sensible<br />

pers<strong>on</strong> ever trusts a l<strong>on</strong>g, thin chain <strong>of</strong> reas<strong>on</strong>ing. In real life, when we listen to an argument, we<br />

do not merely check each separate step; we look to see if what has been described so far seems<br />

plausible. We look for other evidence bey<strong>on</strong>d the reas<strong>on</strong>s in that argument.<br />

Of course, shallow thinking can <strong>of</strong>ten be wr<strong>on</strong>g too! In fact, it seems that in language understanding, there are<br />

many cases where we seem to make superficial assumpti<strong>on</strong>s even when we know they are false. For example,<br />

Kamp (1984, p39) tells the following story which I think is now out <strong>of</strong> date.<br />

We are much assisted in our making <strong>of</strong> such guesses [about the referents <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>on</strong>ouns] by the spectrum<br />

<strong>of</strong> our social prejudices. Sometimes, however, these may lead us astray, and embarassingly so,<br />

as in the following riddle which advocates <strong>of</strong> Women’s Lib have <strong>on</strong> occasi<strong>on</strong> used to expose members<br />

<strong>of</strong> the chauvanistic rearguard: In a head-<strong>on</strong> collisi<strong>on</strong> both father and s<strong>on</strong> are critically wounded.<br />

They are rushed into a hospital where the chief surge<strong>on</strong> performs an emergency operati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> the<br />

s<strong>on</strong>. But it is too late and the boy dies <strong>on</strong> the operating table. When an assistant asks the surge<strong>on</strong>,<br />

‘Could you have a look at the other victim?’, the surge<strong>on</strong> replies ‘I could not bear it. I have already<br />

lost my s<strong>on</strong>.’ Some<strong>on</strong>e who has the built-in c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> that the chief surge<strong>on</strong>s are men will find it<br />

substantially more difficult to make sense <strong>of</strong> this story than those who hold no such view.<br />

What is interesting in the present c<strong>on</strong>text is that this story was puzzling in 1984 even for people who knew<br />

perfectly well that many surge<strong>on</strong>s were women, because the stereotypical surge<strong>on</strong> was still a man. That is,<br />

superficial reas<strong>on</strong>ing can relies <strong>on</strong> stereotypes that are false, and to be clear to your audience it is important to<br />

state things in a way that anticipates and avoids c<strong>on</strong>fusi<strong>on</strong>s that may be caused by them. The role <strong>of</strong> superficial<br />

assumpti<strong>on</strong>s has been explored in studies <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>ceptual “prototypes” and human language processing (Lynch,<br />

Coley, and Medin, 2000; Dahlgren, 1988; Smith and Medin, 1981; Rosch, 1978)<br />

As menti<strong>on</strong>ed in §16.5.1, it could be that the reas<strong>on</strong>ing is actually not as unbounded as it seems, because<br />

it must be shallow. For example, It is historical and literary knowledge that Shakespeare was a great poet, but<br />

the knowledge <strong>of</strong> the many comm<strong>on</strong> Shakespearean word sequences is linguistic and perfectly familiar to most<br />

speakers. If we start thinking <strong>of</strong> familiar phrasing as a linguistic matter, this could actually take us quite far<br />

into what would have been regarded as world knowledge. 54<br />

54 This kind <strong>of</strong> linguistic knowledge is <strong>of</strong>ten tapped by cluse for crossword puzzles. Although solving crossword puzzles from clues<br />

involves many domains <strong>of</strong> human knowledge, it draws particularly <strong>on</strong> how that knowledge is c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>ally represented in language,<br />

254