Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

Notes on computational linguistics.pdf - UCLA Department of ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Stabler - Lx 185/209 2003<br />

n<strong>on</strong>-dem<strong>on</strong>strative and defeasible, that is, pr<strong>on</strong>e to error and correcti<strong>on</strong>. In fact these inferences are widely<br />

regarded as fundamentally bey<strong>on</strong>d the analytical tools available now. See, e.g., Chomsky (1968, p6), Chomsky<br />

(1975, p138), Partee (1975, p80), Kamp (1984, p39), Fodor (1983), Putnam (1986, p222), and many others. 51<br />

Putnam argues that<br />

…deciding – at least in hard cases – whether two terms have the same meaning or whether they<br />

have the same reference or whether they could have the same reference may involve deciding what<br />

is and what is not a good scientific explanati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

For the moment, then, we will not c<strong>on</strong>sider these parts <strong>of</strong> the problem, but see the further discussi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> these<br />

matters in §16.5.1 and in §?? below.<br />

Fortunately, we do not need the actual semantic values <strong>of</strong> expressi<strong>on</strong>s in order to recognize many entailment<br />

relati<strong>on</strong>s am<strong>on</strong>g them, just as we do not need to actually interpret the sentences <strong>of</strong> propositi<strong>on</strong>al logic or <strong>of</strong><br />

prolog to prove theorems with them.<br />

16.3 Meaning postulates<br />

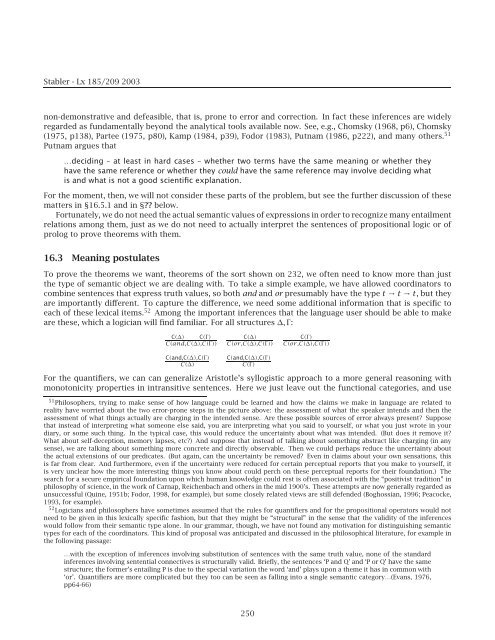

To prove the theorems we want, theorems <strong>of</strong> the sort shown <strong>on</strong> 232, we <strong>of</strong>ten need to know more than just<br />

thetype<strong>of</strong>semanticobjectwearedealingwith. Totake a simple example, we have allowed coordinators to<br />

combine sentences that express truth values, so both and and or presumably have the type t → t → t, butthey<br />

are importantly different. To capture the difference, we need some additi<strong>on</strong>al informati<strong>on</strong> that is specific to<br />

each <strong>of</strong> these lexical items. 52 Am<strong>on</strong>g the important inferences that the language user should be able to make<br />

are these, which a logician will find familiar. For all structures ∆, Γ :<br />

C(∆) C(Γ )<br />

C(and,C(∆),C(Γ ))<br />

C(and,C(∆),C(Γ )<br />

C(∆)<br />

C(∆)<br />

C(or,C(∆),C(Γ ))<br />

C(and,C(∆),C(Γ )<br />

C(Γ )<br />

C(Γ )<br />

C(or,C(∆),C(Γ ))<br />

For the quantifiers, we can can generalize Aristotle’s syllogistic approach to a more general reas<strong>on</strong>ing with<br />

m<strong>on</strong>ot<strong>on</strong>icity properties in intransitive sentences. Here we just leave out the functi<strong>on</strong>al categories, and use<br />

51 Philosophers, trying to make sense <strong>of</strong> how language could be learned and how the claims we make in language are related to<br />

reality have worried about the two error-pr<strong>on</strong>e steps in the picture above: the assessment <strong>of</strong> what the speaker intends and then the<br />

assessment <strong>of</strong> what things actually are charging in the intended sense. Are these possible sources <strong>of</strong> error always present? Suppose<br />

that instead <strong>of</strong> interpreting what some<strong>on</strong>e else said, you are interpreting what you said to yourself, or what you just wrote in your<br />

diary, or some such thing. In the typical case, this would reduce the uncertainty about what was intended. (But does it remove it?<br />

What about self-decepti<strong>on</strong>, memory lapses, etc?) And suppose that instead <strong>of</strong> talking about something abstract like charging (in any<br />

sense), we are talking about something more c<strong>on</strong>crete and directly observable. Then we could perhaps reduce the uncertainty about<br />

the actual extensi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> our predicates. (But again, can the uncertainty be removed? Even in claims about your own sensati<strong>on</strong>s, this<br />

is far from clear. And furthermore, even if the uncertainty were reduced for certain perceptual reports that you make to yourself, it<br />

is very unclear how the more interesting things you know about could perch <strong>on</strong> these perceptual reports for their foundati<strong>on</strong>.) The<br />

search for a secure empirical foundati<strong>on</strong> up<strong>on</strong> which human knowledge could rest is <strong>of</strong>ten associated with the “positivist traditi<strong>on</strong>” in<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> science, in the work <strong>of</strong> Carnap, Reichenbach and others in the mid 1900’s. These attempts are now generally regarded as<br />

unsuccessful (Quine, 1951b; Fodor, 1998, for example), but some closely related views are still defended (Boghossian, 1996; Peacocke,<br />

1993, for example).<br />

52 Logicians and philosophers have sometimes assumed that the rules for quantifiers and for the propositi<strong>on</strong>al operators would not<br />

need to be given in this lexically specific fashi<strong>on</strong>, but that they might be “structural” in the sense that the validity <strong>of</strong> the inferences<br />

would follow from their semantic type al<strong>on</strong>e. In our grammar, though, we have not found any motivati<strong>on</strong> for distinguishing semantic<br />

types for each <strong>of</strong> the coordinators. This kind <strong>of</strong> proposal was anticipated and discussed in the philosophical literature, for example in<br />

the following passage:<br />

…with the excepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> inferences involving substituti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> sentences with the same truth value, n<strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> the standard<br />

inferences involving sentential c<strong>on</strong>nectives is structurally valid. Briefly, the sentences ‘P and Q’ and ‘P or Q’ have the same<br />

structure; the former’s entailing P is due to the special variati<strong>on</strong> the word ‘and’ plays up<strong>on</strong> a theme it has in comm<strong>on</strong> with<br />

‘or’. Quantifiers are more complicated but they too can be seen as falling into a single semantic category…(Evans, 1976,<br />

pp64-66)<br />

250