Animal Influence I - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Animal Influence I - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Animal Influence I - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

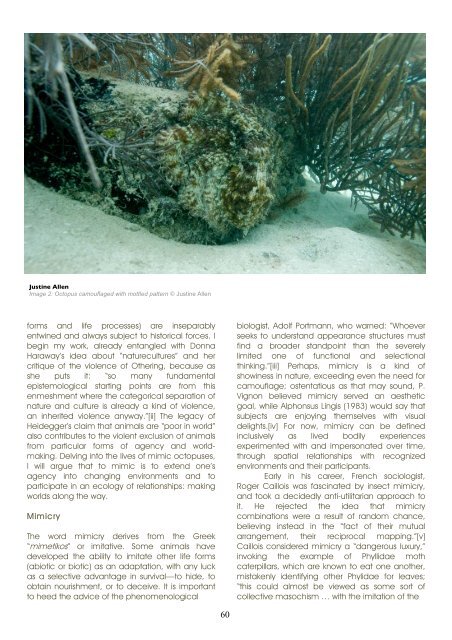

Just<strong>in</strong>e Allen<br />

Image 2: Octopus camouflaged with mottled pattern Just<strong>in</strong>e Allen<br />

forms and life processes) are <strong>in</strong>separably<br />

entw<strong>in</strong>ed and always subject to historical forces. I<br />

beg<strong>in</strong> my work, already entangled with Donna<br />

Haraway’s idea about “naturecultures” and her<br />

critique <strong>of</strong> the violence <strong>of</strong> Other<strong>in</strong>g, because as<br />

she puts it: “so many fundamental<br />

epistemological start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts are from this<br />

enmeshment where the categorical separation <strong>of</strong><br />

nature and culture is already a k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> violence,<br />

an <strong>in</strong>herited violence anyway.”[ii] <strong>The</strong> legacy <strong>of</strong><br />

Heidegger’s claim that animals are “poor <strong>in</strong> world”<br />

also contributes to the violent exclusion <strong>of</strong> animals<br />

from particular forms <strong>of</strong> agency and worldmak<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Delv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to the lives <strong>of</strong> mimic octopuses,<br />

I will argue that to mimic is to extend one’s<br />

agency <strong>in</strong>to chang<strong>in</strong>g environments and to<br />

participate <strong>in</strong> an ecology <strong>of</strong> relationships: mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

worlds along the way.<br />

Mimicry<br />

<strong>The</strong> word mimicry derives from the Greek<br />

“mimetikos” or imitative. Some animals have<br />

developed the ability to imitate other life forms<br />

(abiotic or biotic) as an adaptation, with any luck<br />

as a selective advantage <strong>in</strong> survival—to hide, to<br />

obta<strong>in</strong> nourishment, or to deceive. It is important<br />

to heed the advice <strong>of</strong> the phenomenological<br />

60<br />

biologist, Adolf Portmann, who warned: “Whoever<br />

seeks to understand appearance structures must<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d a broader standpo<strong>in</strong>t than the severely<br />

limited one <strong>of</strong> functional and selectional<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g.”[iii] Perhaps, mimicry is a k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong><br />

show<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong> nature, exceed<strong>in</strong>g even the need for<br />

camouflage; ostentatious as that may sound, P.<br />

Vignon believed mimicry served an aesthetic<br />

goal, while Alphonsus L<strong>in</strong>gis (1983) would say that<br />

subjects are enjoy<strong>in</strong>g themselves with visual<br />

delights.[iv] For now, mimicry can be def<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusively as lived bodily experiences<br />

experimented with and impersonated over time,<br />

through spatial relationships with recognized<br />

environments and their participants.<br />

Early <strong>in</strong> his career, French sociologist,<br />

Roger Caillois was fasc<strong>in</strong>ated by <strong>in</strong>sect mimicry,<br />

and took a decidedly anti-utilitarian approach to<br />

it. He rejected the idea that mimicry<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>ations were a result <strong>of</strong> random chance,<br />

believ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>in</strong> the “fact <strong>of</strong> their mutual<br />

arrangement, their reciprocal mapp<strong>in</strong>g.”[v]<br />

Caillois considered mimicry a “dangerous luxury,”<br />

<strong>in</strong>vok<strong>in</strong>g the example <strong>of</strong> Phyllidae moth<br />

caterpillars, which are known to eat one another,<br />

mistakenly identify<strong>in</strong>g other Phylidae for leaves;<br />

“this could almost be viewed as some sort <strong>of</strong><br />

collective masochism … with the imitation <strong>of</strong> the