Connectionist Modeling of Experience-based Effects in Sentence ...

Connectionist Modeling of Experience-based Effects in Sentence ...

Connectionist Modeling of Experience-based Effects in Sentence ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

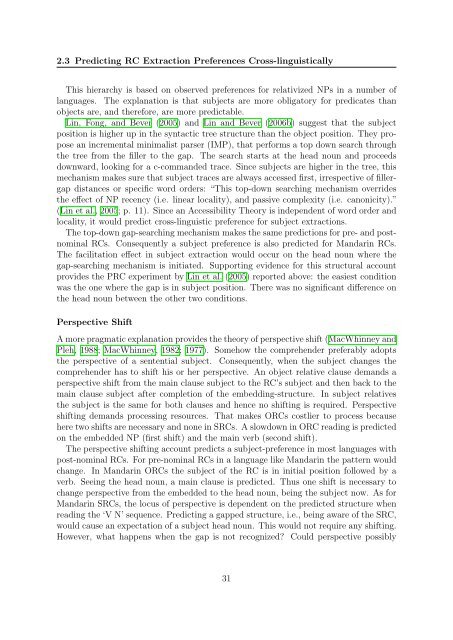

2.3 Predict<strong>in</strong>g RC Extraction Preferences Cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistically<br />

This hierarchy is <strong>based</strong> on observed preferences for relativized NPs <strong>in</strong> a number <strong>of</strong><br />

languages. The explanation is that subjects are more obligatory for predicates than<br />

objects are, and therefore, are more predictable.<br />

L<strong>in</strong>, Fong, and Bever (2005) and L<strong>in</strong> and Bever (2006b) suggest that the subject<br />

position is higher up <strong>in</strong> the syntactic tree structure than the object position. They propose<br />

an <strong>in</strong>cremental m<strong>in</strong>imalist parser (IMP), that performs a top down search through<br />

the tree from the filler to the gap. The search starts at the head noun and proceeds<br />

downward, look<strong>in</strong>g for a c-commanded trace. S<strong>in</strong>ce subjects are higher <strong>in</strong> the tree, this<br />

mechanism makes sure that subject traces are always accessed first, irrespective <strong>of</strong> fillergap<br />

distances or specific word orders: “This top-down search<strong>in</strong>g mechanism overrides<br />

the effect <strong>of</strong> NP recency (i.e. l<strong>in</strong>ear locality), and passive complexity (i.e. canonicity).”<br />

(L<strong>in</strong> et al., 2005; p. 11). S<strong>in</strong>ce an Accessibility Theory is <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> word order and<br />

locality, it would predict cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic preference for subject extractions.<br />

The top-down gap-search<strong>in</strong>g mechanism makes the same predictions for pre- and postnom<strong>in</strong>al<br />

RCs. Consequently a subject preference is also predicted for Mandar<strong>in</strong> RCs.<br />

The facilitation effect <strong>in</strong> subject extraction would occur on the head noun where the<br />

gap-search<strong>in</strong>g mechanism is <strong>in</strong>itiated. Support<strong>in</strong>g evidence for this structural account<br />

provides the PRC experiment by L<strong>in</strong> et al. (2005) reported above: the easiest condition<br />

was the one where the gap is <strong>in</strong> subject position. There was no significant difference on<br />

the head noun between the other two conditions.<br />

Perspective Shift<br />

A more pragmatic explanation provides the theory <strong>of</strong> perspective shift (MacWh<strong>in</strong>ney and<br />

Pleh, 1988; MacWh<strong>in</strong>ney, 1982; 1977). Somehow the comprehender preferably adopts<br />

the perspective <strong>of</strong> a sentential subject. Consequently, when the subject changes the<br />

comprehender has to shift his or her perspective. An object relative clause demands a<br />

perspective shift from the ma<strong>in</strong> clause subject to the RC’s subject and then back to the<br />

ma<strong>in</strong> clause subject after completion <strong>of</strong> the embedd<strong>in</strong>g-structure. In subject relatives<br />

the subject is the same for both clauses and hence no shift<strong>in</strong>g is required. Perspective<br />

shift<strong>in</strong>g demands process<strong>in</strong>g resources. That makes ORCs costlier to process because<br />

here two shifts are necessary and none <strong>in</strong> SRCs. A slowdown <strong>in</strong> ORC read<strong>in</strong>g is predicted<br />

on the embedded NP (first shift) and the ma<strong>in</strong> verb (second shift).<br />

The perspective shift<strong>in</strong>g account predicts a subject-preference <strong>in</strong> most languages with<br />

post-nom<strong>in</strong>al RCs. For pre-nom<strong>in</strong>al RCs <strong>in</strong> a language like Mandar<strong>in</strong> the pattern would<br />

change. In Mandar<strong>in</strong> ORCs the subject <strong>of</strong> the RC is <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial position followed by a<br />

verb. See<strong>in</strong>g the head noun, a ma<strong>in</strong> clause is predicted. Thus one shift is necessary to<br />

change perspective from the embedded to the head noun, be<strong>in</strong>g the subject now. As for<br />

Mandar<strong>in</strong> SRCs, the locus <strong>of</strong> perspective is dependent on the predicted structure when<br />

read<strong>in</strong>g the ‘V N’ sequence. Predict<strong>in</strong>g a gapped structure, i.e., be<strong>in</strong>g aware <strong>of</strong> the SRC,<br />

would cause an expectation <strong>of</strong> a subject head noun. This would not require any shift<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

However, what happens when the gap is not recognized? Could perspective possibly<br />

31