You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

June, 1905 COAL AND TIMBER 9<br />

the quantity of coal charged or put into<br />

the ovens varies according to size of the<br />

ovens, the size of the larries vary accordingly.<br />

In the larger ovens, A]/ 2 tons of<br />

coal is the usual charge for 48-hour coke,<br />

and six tons for 72-hour coke. This yields<br />

67 per cent, of coke after being burned<br />

and drawn.<br />

It is during the burning process that the<br />

judgment of the coke maker comes into<br />

requisition, and good judgment is an absolute<br />

necessity in the manufacture of the<br />

best coke. Beside the opening in the top<br />

of the oven, referred to as the "trunnel<br />

head," there is a large opening in the front,<br />

about 26x30 inches, called the door, through<br />

which the coke is drawn out; but which is<br />

kept closed during the process of burning.<br />

After having charged the oven the next<br />

step in the process is to level the charge.<br />

This is done through the door by means of<br />

a long iron rod with a scraper affixed to<br />

the end. The door is then walled up with<br />

fire brick and plastered over with a luting<br />

made of fine sharp sand or good loam. In<br />

about 30 minutes a pale blue smoke arises<br />

out of the trunnel head, from which the<br />

damper has been previously removed. The<br />

smoke gradually grows darker in color and<br />

stronger in volume, until about 30 minutes<br />

later it goes off with a puff similar to the<br />

explosion of a small charge of powder. This<br />

signifies that the charge of coal has ignited<br />

and that the burning has begun.<br />

The charge of coal burns from the top<br />

downward, and the process of burning, or<br />

"airing" as the workmen call it, is regulated<br />

through the door by means of little<br />

holes made around the arch. Through these<br />

openings the air is admitted while the smoke<br />

and impurities are expelled from the oven<br />

and the coking mass of coal through the<br />

trunnel head.<br />

In about 72 hours after the oven has been<br />

charged, if properly handled, the oven will<br />

be "around," or coked, and good foundrj'<br />

coke should be the result. When the oven<br />

is "around" it looks like a mass of red hot<br />

coals. The process of "drawing" the oven<br />

then begins This was done formerly by<br />

means of the same instrument as that used<br />

for the leveling of the oven after first being<br />

charged. Now machinery has been devised<br />

and the work of drawng the oven<br />

much simplified and expedited. The drawing<br />

must await the cooling of the superheated<br />

mass. The coke drawers knock the<br />

doors down and by means of a hose to<br />

which a long piece of gas pipe is attached,<br />

spray the mass with water until sufficiently<br />

cooled to admit of its being handled. When<br />

the coke is thoroughly cooled it is drawn<br />

from the oven and is ready for loading upon<br />

railway cars unless it is desired that it<br />

be first crushed to any required size.<br />

When the ovens are first fired,or started,<br />

the coal is ignited by means of wood or red<br />

hot coals, the same as the starting of any<br />

other coal fire. After repeated chargings<br />

the ovens become hot and the coal is ig.-<br />

nited by the mere heat which the ovens<br />

retain in their walls from the former<br />

charges. For cooling the coked coal, pure<br />

water is an absolute essential to insure<br />

the best and most perfect coke. If the<br />

water contains sulphur and any other impurities,<br />

the coke will absorb them and this<br />

in turn will become injurious to metals<br />

manufactured with them. The coke from<br />

the Pocahontas and Connellsville fields s<br />

of silvery lustre, cellular, with a metallic<br />

ring, tenacious and very free from inherent<br />

impurities. It is so tough that it is capable<br />

of bearing an extremely heavy burden<br />

in the blast furnace. Its porosity and ability<br />

to stand up in a furnace, and the extremely<br />

low percentage of sulphur is what has<br />

given it such a reputation as blast furnace<br />

fuel, and has created the demand that exists<br />

for it in all parts of this country.<br />

All bituminous coals do not make good<br />

coke. Even Pennsylvania coals are defici-<br />

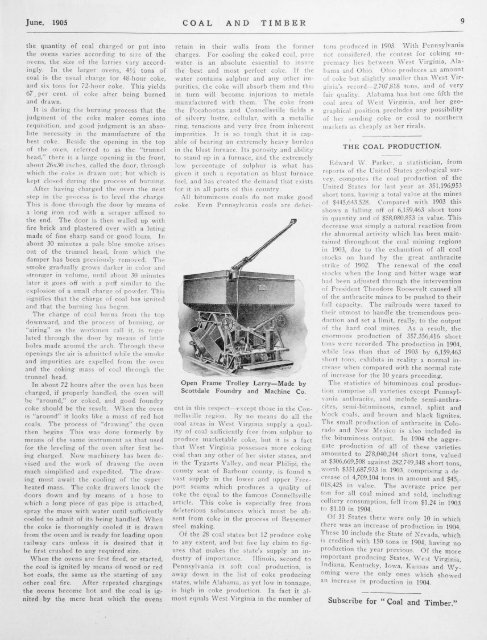

Open Frame Trolley Larry—Made by<br />

Scottdale Foundry and Machine Co.<br />

ent in this respect—except those in the Connellsville<br />

region. By no means do all the<br />

coal areas in West Virginia supply a quality<br />

of coal sufficiently free from sulphur to<br />

produce marketable coke, but it is a fact<br />

that West Virginia possesses more coking<br />

coal than any other of her sister states, and<br />

in the Tygarts Valley, and near Philipi, the<br />

county seat of Barbour county, is found a<br />

vast supply in the lower and upper Freeport<br />

seams which produces a quality of<br />

coke the equal to the famous Connellsville<br />

article. This coke is especially free from<br />

deleterious substances which must be absent<br />

from coke in the process of Bessemer<br />

steel making.<br />

Of the 28 coal states but 12 produce coke<br />

to any extent, and but five lay claim to figures<br />

that makes the state's supply an industry<br />

of importance. Illinois, second to<br />

Pennsylvania in soft coal production, is<br />

away down in the list of coke producing<br />

states, while Alabama, as yet low in tonnage,<br />

is high in coke production. In fact it almost<br />

equals West Virginia in the number of<br />

tons produced in 1903. With Pennsylvania<br />

not considered, the contest for coking supremacy<br />

lies between West Virginia, Alabama<br />

and Ohio.<br />

Ohio produces an amount<br />

of coke but slightly smaller than West Virginia's<br />

record—2,707,818 tons, and of very<br />

fair quality. Alabama has but one fifththe<br />

coal area of West Virginia, and her geographical<br />

position, precludes any possibility<br />

of her sending coke or coal to northern<br />

markets as cheaply as her rivals.<br />

THE COAL PRODUCTION.<br />

Edward W. Parker, a statistician, from<br />

reports of the United States geological survey,<br />

computes the coal production of the<br />

United States for last year as 351,196,953<br />

short tons, having a total value at the mines<br />

of $445,643,528. Compared with 1903 this<br />

shows a falling off of 6,159,463 short tons<br />

in quantity and of $58,080,853 in value. This<br />

decrease was simply a natural reaction from<br />

the abnormal activity which has been maintained<br />

throughout the coal mining regions<br />

in 1903, due to the exhaustion of all coal<br />

stocks on hand by the great anthracite<br />

strike of 1902. The renewal of the coal<br />

stocks when the long and bitter wage war<br />

had been adjusted through the intervention<br />

of President Theodore Roosevelt caused all<br />

of the anthracite mines to be pushed to their<br />

full capacity. The railroads were taxed to<br />

their utmost to handle the tremendous production<br />

and set a limit, really, to the output<br />

of the hard coal mines. As a result, the<br />

enormous production of 357,356,416 short<br />

tons were recorded. The production in 1904,<br />

while less than that of 1903 by 6,159,463<br />

short tons, exhibits in reality a normal increase<br />

when compared with the normal rate<br />

of increase for the 10 years preceding.<br />

The statistics of bituminous coal production<br />

comprise all varieties except Pennsylvania<br />

anthracite, and include semi-anthracites,<br />

semi-bituminous, cannel, splint and<br />

block coals, and brown and black lignites.<br />

The small production of anthracite in Colorado<br />

and New Mexico is also included in<br />

the bituminous output. In 1904 the aggregate<br />

production of all of these varieties<br />

amounted to 278,040,244 short tons, valued<br />

at $306,669,508 against 282,749,348 short tons,<br />

worth $351,687,933 in 1903, comprising a decrease<br />

of 4,709,104 tons in amount and $45,-<br />

018,425 in value. The average price per<br />

ton for all coal mined and sold, including<br />

colliery consumption, fell from $1.24 in 1903<br />

to $1.10 in 1904.<br />

Of 31 States there were only 10 in which<br />

there was an increase of production in 1904.<br />

These 10 include the State of Nevada, which<br />

is credited with 150 tons in 1904, having no<br />

production the year previous. Of the more<br />

important producing States, West Virginia,<br />

Indiana, Kentucky, Iowa, Kansas and Wyoming<br />

were the only ones which<br />

an increase in production in 1904.<br />

showed<br />

Subscribe for " Coal and Timber."