… and the Pursuit of Happiness - Institute of Economic Affairs

… and the Pursuit of Happiness - Institute of Economic Affairs

… and the Pursuit of Happiness - Institute of Economic Affairs

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>…</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> pursuit <strong>of</strong> happiness<br />

are more equal countries happier?<br />

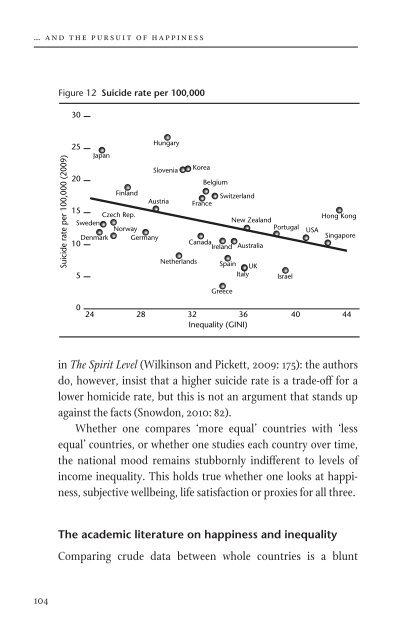

Figure 12 Suicide rate per 100,000 1<br />

2<br />

30<br />

3<br />

Hungary<br />

4<br />

25<br />

Japan<br />

5<br />

Slovenia<br />

Korea<br />

6<br />

20<br />

Belgium<br />

7<br />

Finl<strong>and</strong><br />

Switzerl<strong>and</strong><br />

Austria France<br />

8<br />

15<br />

Czech Rep.<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Sweden<br />

New Zeal<strong>and</strong><br />

9<br />

Norway<br />

Portugal<br />

USA<br />

Denmark Germany<br />

Singapore<br />

10<br />

10<br />

Canada<br />

Irel<strong>and</strong> Australia<br />

11<br />

Ne<strong>the</strong>rl<strong>and</strong>s Spain UK<br />

12<br />

5<br />

Italy Israel<br />

13<br />

Greece<br />

14<br />

0<br />

24 28 32 36 40 44<br />

15<br />

Inequality (GINI)<br />

16<br />

17<br />

18<br />

19<br />

20<br />

21<br />

22<br />

23<br />

24<br />

25<br />

26<br />

Source: Statistics from <strong>Institute</strong> for Fiscal Studies (2010)<br />

27<br />

28<br />

The academic literature on happiness <strong>and</strong> inequality<br />

29<br />

30<br />

Suicide rate per 100,000 (2009)<br />

in The Spirit Level (Wilkinson <strong>and</strong> Pickett, 2009: 175): <strong>the</strong> authors<br />

do, however, insist that a higher suicide rate is a trade-<strong>of</strong>f for a<br />

lower homicide rate, but this is not an argument that st<strong>and</strong>s up<br />

against <strong>the</strong> facts (Snowdon, 2010: 82).<br />

Whe<strong>the</strong>r one compares ‘more equal’ countries with ‘less<br />

equal’ countries, or whe<strong>the</strong>r one studies each country over time,<br />

<strong>the</strong> national mood remains stubbornly indifferent to levels <strong>of</strong><br />

income inequality. This holds true whe<strong>the</strong>r one looks at happiness,<br />

subjective wellbeing, life satisfaction or proxies for all three.<br />

Comparing crude data between whole countries is a blunt<br />

instrument, but more sophisticated attempts to test whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

inequality affects happiness have not produced compelling<br />

evidence. Perhaps <strong>the</strong> most thought-provoking <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se was <strong>the</strong><br />

study by Alesina et al. (2004), which found that happiness was<br />

sometimes affected by inequality, but was principally dependent<br />

on social attitudes ra<strong>the</strong>r than inequality per se, a conclusion<br />

echoed by Biancotti <strong>and</strong> D’Alessio (2008), Hopkins (2008) <strong>and</strong><br />

Bjørnskov et al. (2010). While it might be expected that <strong>the</strong> rich<br />

would be less troubled by inequality than <strong>the</strong> poor, this was not<br />

necessarily <strong>the</strong> case. Alesina et al. found low-income Europeans to<br />

be averse to inequality, while low-income Americans were ‘totally<br />

unaffected’. Rich Americans were <strong>of</strong>ten more averse to inequality<br />

than <strong>the</strong>ir poorer compatriots, while left-wingers were more sensitive<br />

to changes in wealth distribution on both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Atlantic.<br />

Alesina et al. explained <strong>the</strong> paradox <strong>of</strong> American tolerance<br />

to inequality, despite a wealth gap that dwarfs most European<br />

countries, by reference to <strong>the</strong> prevailing belief that wealth is <strong>the</strong><br />

product <strong>of</strong> hard work <strong>and</strong> merit – a view that is widely shared in<br />

Europe only by <strong>the</strong> rich. In contrast to Europeans, Americans are<br />

inclined to view inequality as justified <strong>and</strong> wealth redistribution<br />

as unfair. Americans have greater faith in social mobility, with <strong>the</strong><br />

poor expecting to move up <strong>the</strong> ladder <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> rich fearing <strong>the</strong>y<br />

might move down. Alesina et al. found that 60 per cent <strong>of</strong> Europeans<br />

believed <strong>the</strong> poor were trapped in poverty, while only 30<br />

per cent <strong>of</strong> Americans felt <strong>the</strong> same way. When asked whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

poor were lazy, <strong>the</strong> percentages were exactly reversed.<br />

Regardless <strong>of</strong> whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>se beliefs are grounded in reality,<br />

<strong>the</strong> study showed that perceptions <strong>of</strong> fairness <strong>and</strong> social mobility<br />

are more important than inequality itself. Some people are made<br />

less happy by inequality while o<strong>the</strong>rs ra<strong>the</strong>r like it. A greater<br />

104 105