Proceedings of the Seventh Mountain Lion Workshop

Proceedings of the Seventh Mountain Lion Workshop

Proceedings of the Seventh Mountain Lion Workshop

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

look bigger, but <strong>the</strong> cat continued to<br />

advance. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> women snarled like a<br />

dog and “mock lunged,” and <strong>the</strong> puma ran<br />

into some bushes. A nearby rancher<br />

approached on horseback, accompanied by 2<br />

dogs. When <strong>the</strong>y directed <strong>the</strong>ir attention<br />

toward where <strong>the</strong> girls thought <strong>the</strong> puma<br />

was, it bounded <strong>of</strong>f (Linda Lewis, web site:<br />

, citing personal communications<br />

with Jessie Dickson, April 18-19, 2001).<br />

In probably <strong>the</strong> most dramatic example<br />

demonstrating puma behavior following<br />

human aggressiveness, a deer hunter and a<br />

puma were stalking <strong>the</strong> same deer when <strong>the</strong><br />

deer detected <strong>the</strong> puma and fled. From 27<br />

m (30 yards) away, <strong>the</strong> puma transferred its<br />

stalk to <strong>the</strong> hunter. The hunter hid behind a<br />

tree while <strong>the</strong> puma approached, crouching.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> puma got close <strong>the</strong> hunter jumped out<br />

and yelled. That puma left running (Ford<br />

1994). The puma obviously knew <strong>the</strong> hunter<br />

was behind <strong>the</strong> tree, but <strong>the</strong> hunter’s actions<br />

probably appeared to <strong>the</strong> puma as an attack<br />

coming from a hidden (ambush) position.<br />

The action successfully interrupted <strong>the</strong><br />

predatory stalking behavior and instigated a<br />

flight behavior.<br />

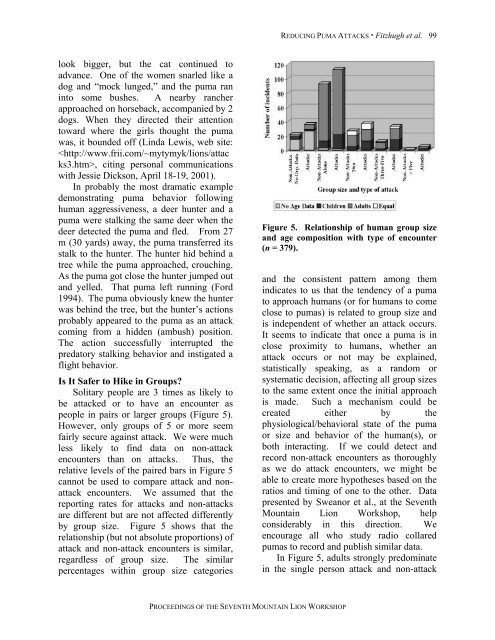

Is It Safer to Hike in Groups?<br />

Solitary people are 3 times as likely to<br />

be attacked or to have an encounter as<br />

people in pairs or larger groups (Figure 5).<br />

However, only groups <strong>of</strong> 5 or more seem<br />

fairly secure against attack. We were much<br />

less likely to find data on non-attack<br />

encounters than on attacks. Thus, <strong>the</strong><br />

relative levels <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> paired bars in Figure 5<br />

cannot be used to compare attack and nonattack<br />

encounters. We assumed that <strong>the</strong><br />

reporting rates for attacks and non-attacks<br />

are different but are not affected differently<br />

by group size. Figure 5 shows that <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship (but not absolute proportions) <strong>of</strong><br />

attack and non-attack encounters is similar,<br />

regardless <strong>of</strong> group size. The similar<br />

percentages within group size categories<br />

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SEVENTH MOUNTAIN LION WORKSHOP<br />

REDUCING PUMA ATTACKS · Fitzhugh et al. 99<br />

Figure 5. Relationship <strong>of</strong> human group size<br />

and age composition with type <strong>of</strong> encounter<br />

(n = 379).<br />

and <strong>the</strong> consistent pattern among <strong>the</strong>m<br />

indicates to us that <strong>the</strong> tendency <strong>of</strong> a puma<br />

to approach humans (or for humans to come<br />

close to pumas) is related to group size and<br />

is independent <strong>of</strong> whe<strong>the</strong>r an attack occurs.<br />

It seems to indicate that once a puma is in<br />

close proximity to humans, whe<strong>the</strong>r an<br />

attack occurs or not may be explained,<br />

statistically speaking, as a random or<br />

systematic decision, affecting all group sizes<br />

to <strong>the</strong> same extent once <strong>the</strong> initial approach<br />

is made. Such a mechanism could be<br />

created ei<strong>the</strong>r by <strong>the</strong><br />

physiological/behavioral state <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> puma<br />

or size and behavior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> human(s), or<br />

both interacting. If we could detect and<br />

record non-attack encounters as thoroughly<br />

as we do attack encounters, we might be<br />

able to create more hypo<strong>the</strong>ses based on <strong>the</strong><br />

ratios and timing <strong>of</strong> one to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. Data<br />

presented by Sweanor et al., at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Seventh</strong><br />

<strong>Mountain</strong> <strong>Lion</strong> <strong>Workshop</strong>, help<br />

considerably in this direction. We<br />

encourage all who study radio collared<br />

pumas to record and publish similar data.<br />

In Figure 5, adults strongly predominate<br />

in <strong>the</strong> single person attack and non-attack