Accessibility and Street Layout Exploring spatial equity in

Accessibility and Street Layout Exploring spatial equity in

Accessibility and Street Layout Exploring spatial equity in

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

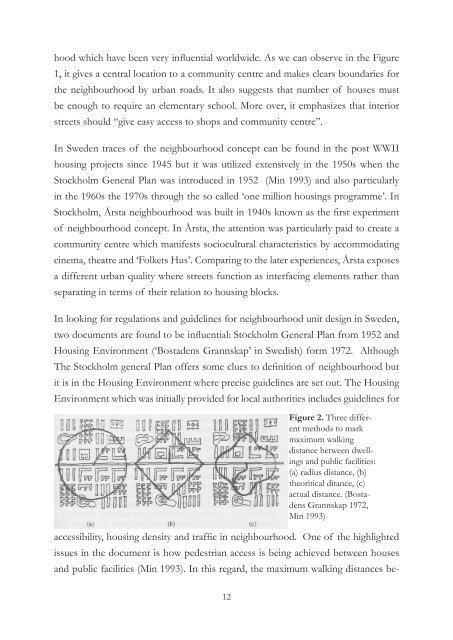

hood which have been very <strong>in</strong>fluential worldwide. As we can observe <strong>in</strong> the Figure<br />

1, it gives a central location to a community centre <strong>and</strong> makes clears boundaries for<br />

the neighbourhood by urban roads. It also suggests that number of houses must<br />

be enough to require an elementary school. More over, it emphasizes that <strong>in</strong>terior<br />

streets should “give easy access to shops <strong>and</strong> community centre”.<br />

In Sweden traces of the neighbourhood concept can be found <strong>in</strong> the post WWII<br />

hous<strong>in</strong>g projects s<strong>in</strong>ce 1945 but it was utilized extensively <strong>in</strong> the 1950s when the<br />

Stockholm General Plan was <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> 1952 (M<strong>in</strong> 1993) <strong>and</strong> also particularly<br />

<strong>in</strong> the 1960s the 1970s through the so called ‘one million hous<strong>in</strong>gs programme’. In<br />

Stockholm, Årsta neighbourhood was built <strong>in</strong> 1940s known as the first experiment<br />

of neighbourhood concept. In Årsta, the attention was particularly paid to create a<br />

community centre which manifests sociocultural characteristics by accommodat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

c<strong>in</strong>ema, theatre <strong>and</strong> ‘Folkets Hus’. Compar<strong>in</strong>g to the later experiences, Årsta exposes<br />

a different urban quality where streets function as <strong>in</strong>terfac<strong>in</strong>g elements rather than<br />

separat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> terms of their relation to hous<strong>in</strong>g blocks.<br />

In look<strong>in</strong>g for regulations <strong>and</strong> guidel<strong>in</strong>es for neighbourhood unit design <strong>in</strong> Sweden,<br />

two documents are found to be <strong>in</strong>fluential: Stockholm General Plan from 1952 <strong>and</strong><br />

Hous<strong>in</strong>g Environment (‘Bostadens Grannskap’ <strong>in</strong> Swedish) form 1972. Although<br />

The Stockholm general Plan offers some clues to def<strong>in</strong>ition of neighbourhood but<br />

it is <strong>in</strong> the Hous<strong>in</strong>g Environment where precise guidel<strong>in</strong>es are set out. The Hous<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Environment which was <strong>in</strong>itially provided for local authorities <strong>in</strong>cludes guidel<strong>in</strong>es for<br />

Figure 2. Three different<br />

methods to mark<br />

maximum walk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

distance between dwell<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

<strong>and</strong> public facilities:<br />

(a) radius distance, (b)<br />

theoritical ditance, (c)<br />

actual distance. (Bostadens<br />

Grannskap 1972,<br />

M<strong>in</strong> 1993)<br />

accessibility, hous<strong>in</strong>g density <strong>and</strong> traffic <strong>in</strong> neighbourhood. One of the highlighted<br />

issues <strong>in</strong> the document is how pedestrian access is be<strong>in</strong>g achieved between houses<br />

<strong>and</strong> public facilities (M<strong>in</strong> 1993). In this regard, the maximum walk<strong>in</strong>g distances be-<br />

12