- Page 1 and 2: PART 1. Principles of development i

- Page 3 and 4: PART 2: Early embryonic development

- Page 5 and 6: 15. Lateral plate mesoderm and endo

- Page 7 and 8: Hox Genes: Descent with Modificatio

- Page 9 and 10: The question of growth. How do our

- Page 11 and 12: Embryonic homologies One of the mos

- Page 13 and 14: absent (Figure 1.16A). Over 7000 af

- Page 15 and 16: Such growth, in which the shape is

- Page 17 and 18: One way to search for the chemicals

- Page 19 and 20: 2 3 hours as adults, and they must

- Page 21 and 22: for the following spring's breeding

- Page 23 and 24: VADE MECUM Amphibian development. T

- Page 25 and 26: The formation of a cap is a complex

- Page 27 and 28: In Chlamydomonas, recognition occur

- Page 29 and 30: organism with two distinct and inte

- Page 31 and 32: Aggregation is initiated as each of

- Page 33 and 34: The mathematics of such oscillation

- Page 35 and 36: gonidia to undergo a modified patte

- Page 37 and 38: Sponges develop in a manner so diff

- Page 39 and 40: Embryology provides an endless asso

- Page 41 and 42: Environmental sex determination Sex

- Page 43 and 44: Protection of the egg by sunscreens

- Page 45: The Developmental Mechanics of Cell

- Page 49 and 50: In postulating this model, Weismann

- Page 51 and 52: Insofar as it contains a nucleus, e

- Page 53 and 54: Other tissues may use the same grad

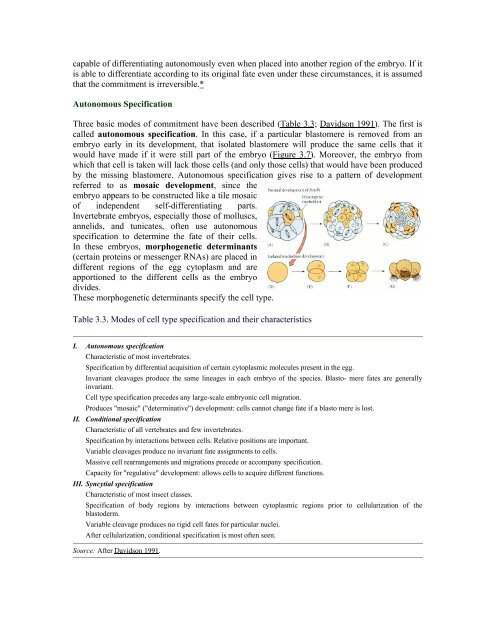

- Page 55 and 56: will give rise to its particular or

- Page 57 and 58: Sydney Brenner (quoted in Wilkins 1

- Page 59 and 60: The results of their experiments we

- Page 61 and 62: This observation led Steinberg to p

- Page 63 and 64: into a single layer of cells (Takei

- Page 65 and 66: 6. In conditional specification, th

- Page 67 and 68: 3. Geneticists had to explain pheno

- Page 69 and 70: These events are not the normal rou

- Page 71 and 72: differentiated; each of them contai

- Page 73 and 74: federal proscription of human cloni

- Page 75 and 76: ecombinase enzymes are active only

- Page 77 and 78: In situ hybridization But where was

- Page 79 and 80: damaged.) The second primer is adde

- Page 81 and 82: By using the appropriate restrictio

- Page 83 and 84: These homozygous mutant mice lacked

- Page 85 and 86: Phenotype Manipulation This technol

- Page 87 and 88: The second approach is candidate ge

- Page 89 and 90: developmental genetics is different

- Page 91 and 92: This gene consists of the following

- Page 93 and 94: In addition to these basal transcri

- Page 95 and 96: Enhancers are critical in the regul

- Page 97 and 98:

The third functional region of MITF

- Page 99 and 100:

A fourth enhancer sequence, located

- Page 101 and 102:

The discovery of the human globin L

- Page 103 and 104:

The results of this procedure are o

- Page 105 and 106:

In vertebrates, the presence of met

- Page 107 and 108:

chromatin that remains condensed th

- Page 109 and 110:

Second, knocking out one Xist locus

- Page 111 and 112:

types of cells (Kleene and Humphrey

- Page 113 and 114:

(Sxl) gene,* while the autosomes pr

- Page 115 and 116:

Table 5.3. Some mRNAs stored in ooc

- Page 117 and 118:

determine the anterior-posterior ax

- Page 119 and 120:

6. Cell-cell communication in devel

- Page 121 and 122:

The inducing tissue does not need i

- Page 123 and 124:

Instructive and permissive interact

- Page 125 and 126:

mouth, whereas the frog tadpole pro

- Page 127 and 128:

are utilized throughout the animal

- Page 129 and 130:

includes the TGF-β family, the act

- Page 131 and 132:

The RTK spans the cell membrane, an

- Page 133 and 134:

members of this family: the C. eleg

- Page 135 and 136:

The Wnt pathway Members of the Wnt

- Page 137 and 138:

The Hedgehog pathway is extremely i

- Page 139 and 140:

A series of mutations has been foun

- Page 141 and 142:

The Nature of Human Syndromes As we

- Page 143 and 144:

vertebral column deformities, myopi

- Page 145 and 146:

The mammalian homologue of CED-4 is

- Page 147 and 148:

In the absence of Notch gene transc

- Page 149 and 150:

extracellular matrix (Figure 6.32).

- Page 151 and 152:

mammary gland tissue. The binding o

- Page 153 and 154:

In some cells, gene transcription r

- Page 155 and 156:

PARTE 2. Early embryonic developmen

- Page 157 and 158:

The means by which sperm are propel

- Page 159 and 160:

The sperm released during ejaculati

- Page 161 and 162:

Lying immediately beneath the plasm

- Page 163 and 164:

The mechanisms of chemotaxis differ

- Page 165 and 166:

Once the sea urchin sperm has penet

- Page 167 and 168:

Removal of these threonine- or seri

- Page 169 and 170:

undergo the acrosomal reaction with

- Page 171 and 172:

Gamete Fusion and the Prevention of

- Page 173 and 174:

The fast block to polyspermy. The f

- Page 175 and 176:

envelope to expand and become the f

- Page 177 and 178:

The calcium ions responsible for th

- Page 179 and 180:

Thus, the conversion of NAD + to NA

- Page 181 and 182:

eticulum (McPherson et al. 1992). T

- Page 183 and 184:

cAMP-dependent protein kinase activ

- Page 185 and 186:

These cells divide to form embryos

- Page 187 and 188:

(Figure 7.34; Elinson and Rowning 1

- Page 189 and 190:

6. In many species, eggs secrete di

- Page 191 and 192:

One consequence of this rapid cell

- Page 193 and 194:

Table 8.1. Karyokinesis and cytokin

- Page 195 and 196:

provides a classification of cleava

- Page 197 and 198:

This occurred at precisely the time

- Page 199 and 200:

These rapid and invariant cell clea

- Page 201 and 202:

The identities of the signaling mol

- Page 203 and 204:

Ingression of primary mesenchyme Fu

- Page 205 and 206:

But these guidance cues cannot be s

- Page 207 and 208:

lastocoel wall (Dan and Okazaki 195

- Page 209 and 210:

The orientation of the cleavage pla

- Page 211 and 212:

stage, the remaining cells divide n

- Page 213 and 214:

embryos can produce these cells, bu

- Page 215 and 216:

Early Development in Tunicates Tuni

- Page 217 and 218:

(or inactivating) specific genes. T

- Page 219 and 220:

occur under laboratory conditions.

- Page 221 and 222:

the germ cells. Using fluorescent a

- Page 223 and 224:

Conditional specification As we saw

- Page 225 and 226:

eggs. Coda This chapter has describ

- Page 227 and 228:

9. The genetics of axis specificati

- Page 229 and 230:

Following cycle 13, the oocyte plas

- Page 231 and 232:

Thus, at the end of germ band forma

- Page 233 and 234:

Classic embryological experiments d

- Page 235 and 236:

posterior region of the unfertilize

- Page 237 and 238:

Further studies have strengthened t

- Page 239 and 240:

The Hunchback protein also works wi

- Page 241 and 242:

transcription factor to activate an

- Page 243 and 244:

The gap genes The gap genes were or

- Page 245 and 246:

Table 9.2. Major genes affecting se

- Page 247 and 248:

The development of the normal patte

- Page 249 and 250:

However, the mechanism by which the

- Page 251 and 252:

As we saw above, the gap gene and p

- Page 253 and 254:

can substitute for Ultrabithorax an

- Page 255 and 256:

The Translocation of Dorsal Protein

- Page 257 and 258:

The Gurken signal is received by th

- Page 259 and 260:

This fate map is generated by the g

- Page 261 and 262:

first glimpses of the multiple leve

- Page 263 and 264:

10. Early development and axis form

- Page 265 and 266:

While these cells are dividing, num

- Page 267 and 268:

The next phase of gastrulation invo

- Page 269 and 270:

Black and Gerhart (1985, 1986) let

- Page 271 and 272:

The convergent extension of the dor

- Page 273 and 274:

During early gastrulation, three ro

- Page 275 and 276:

Spemann concluded from this experim

- Page 277 and 278:

Hans Spemann and Hilde Mangold: Pri

- Page 279 and 280:

We will take up each of these quest

- Page 281 and 282:

Moreover, the injection of exogenou

- Page 283 and 284:

These Nodal-related proteins will a

- Page 285 and 286:

The diffusible proteins of the orga

- Page 287 and 288:

Follistatin. The fourth organizer-s

- Page 289 and 290:

Frzb and Dickkopf. Shortly after th

- Page 291 and 292:

Moreover, when dorsal blastopore li

- Page 293 and 294:

The relationship between these thre

- Page 295 and 296:

Nodal protein activates expression

- Page 297 and 298:

11. The early development of verteb

- Page 299 and 300:

Gastrulation in Fish Embryos The fi

- Page 301 and 302:

If one conceptually opens a Xenopus

- Page 303 and 304:

Left-right axis formation Little is

- Page 305 and 306:

thereby forming the secondary hypob

- Page 307 and 308:

This region, the germinal crescent,

- Page 309 and 310:

Axis Formation in the Chick Embryo

- Page 311 and 312:

The mechanisms for neural induction

- Page 313 and 314:

*Arendt and Nübler-Jung (1999) hav

- Page 315 and 316:

Compaction The fifth, and perhaps t

- Page 317 and 318:

Modifications for development withi

- Page 319 and 320:

The ectodermal precursors end up an

- Page 321 and 322:

These include the genes for transcr

- Page 323 and 324:

Experimental analysis of the hox co

- Page 325 and 326:

Kessel and Gruss (1991) found this

- Page 327 and 328:

Mice homozygous for an insertion mu

- Page 329 and 330:

7. In birds, gravity is critical in

- Page 331 and 332:

This tissue forms the amnionic sac

- Page 333 and 334:

12. The central nervous system and

- Page 335 and 336:

surrounding them. As much as 50% of

- Page 337 and 338:

Cell wedging is intimately linked t

- Page 339 and 340:

Fig 12.6 Human neural tube closure

- Page 341 and 342:

The anterior-posterior axis The ear

- Page 343 and 344:

Ventral patterning of the neural tu

- Page 345 and 346:

The time of this vertical division

- Page 347 and 348:

layer (Wallace 1999). Each Purkinje

- Page 349 and 350:

However, if these cells are transpl

- Page 351 and 352:

Neuronal Types The human brain cons

- Page 353 and 354:

Neurons transmit electrical impulse

- Page 355 and 356:

Development of the Vertebrate Eye A

- Page 357 and 358:

In addition, there are numerous Mü

- Page 359 and 360:

are shed and are replaced by new ce

- Page 361 and 362:

Just as there is a pluripotent neur

- Page 363 and 364:

13. Neural crest cells and axonal s

- Page 365 and 366:

The Trunk Neural Crest Migration pa

- Page 367 and 368:

Recognition of surrounding extracel

- Page 369 and 370:

However, D. J. Anderson's laborator

- Page 371 and 372:

Neural crest cells from rhombomeres

- Page 373 and 374:

the aortic arch arteries and the se

- Page 375 and 376:

Soon afterward, the expression patt

- Page 377 and 378:

Ericson and colleagues (1996) have

- Page 379 and 380:

That it must be a sort of a surface

- Page 381 and 382:

the G growth cone acts abnormally,

- Page 383 and 384:

Guidance by diffusible molecules Ne

- Page 385 and 386:

There is some reciprocity in scienc

- Page 387 and 388:

The activity of the synapse release

- Page 389 and 390:

Growth of the retinal ganglion axon

- Page 391 and 392:

The complicated nerve fiber circuit

- Page 393 and 394:

Snapshot Summary: Neural Crest Cell

- Page 395 and 396:

Fetal Neurons in Adult Hosts In 197

- Page 397 and 398:

Somites give rise to the cells that

- Page 399 and 400:

Eph signaling is thought to mediate

- Page 401 and 402:

(The dermis of other areas of the b

- Page 403 and 404:

Muscle cell fusion The myotome cell

- Page 405 and 406:

The mechanism of intramembranous os

- Page 407 and 408:

mitochondrial energy potential (Sha

- Page 409 and 410:

Mutations in FGFR1 can cause Pfeiff

- Page 411 and 412:

These buds eventually separate from

- Page 413 and 414:

Step 2: The metanephrogenic mesench

- Page 415 and 416:

Step 5: Conversion of the aggregate

- Page 417 and 418:

6. The two myotome regions are spec

- Page 419 and 420:

The Heart The circulatory system is

- Page 421 and 422:

This fusion occurs at about 29 hour

- Page 423 and 424:

Formation of Blood Vessels Although

- Page 425 and 426:

networks of each organ arise within

- Page 427 and 428:

In some instances, angiogenesis may

- Page 429 and 430:

This became apparent when experimen

- Page 431 and 432:

Blood and lymphocyte lineages. Figu

- Page 433 and 434:

Chick cells are readily distinguish

- Page 435 and 436:

In mammalian embryos, food and oxyg

- Page 437 and 438:

*In some infants, the septa fail to

- Page 439 and 440:

As Figure 15.27 shows, the stomach

- Page 441 and 442:

The surfactant enables the alveolar

- Page 443 and 444:

In mammals, the size of the allanto

- Page 445 and 446:

inhibits liver formation (Figure 15

- Page 447 and 448:

Moreover, as will be detailed in Ch

- Page 449 and 450:

These cells secrete the paracrine f

- Page 451 and 452:

Induction of the apical ectodermal

- Page 453 and 454:

The progress zone: The mesodermal c

- Page 455 and 456:

The mechanism by which Hox genes co

- Page 457 and 458:

Thus, while the Hox gene expression

- Page 459 and 460:

Charité and colleagues (1994) have

- Page 461 and 462:

Between the time when the cell's de

- Page 463 and 464:

Snapshot Summary: The Tetrapod Limb

- Page 465 and 466:

This environmental view of sex dete

- Page 467 and 468:

The cells of the seminiferous tubul

- Page 469 and 470:

into the mesenchyme, but stay near

- Page 471 and 472:

There was a strict correlation betw

- Page 473 and 474:

Wnt4: a potential ovary-determining

- Page 475 and 476:

Anti-müllerian duct hormone Anti-M

- Page 477 and 478:

in another (see Jacklin 1981; Bleie

- Page 479 and 480:

Chromosomal Sex Determination in Dr

- Page 481 and 482:

The sex-lethal gene as the pivot fo

- Page 483 and 484:

Doublesex: The switch gene of sex d

- Page 485 and 486:

It is not known whether the tempera

- Page 487 and 488:

18. Metamorphosis, regeneration, an

- Page 489 and 490:

There are no ipsilateral (same-side

- Page 491 and 492:

Organ-specific response to thyroid

- Page 493 and 494:

The more T 3 receptors a tissue has

- Page 495 and 496:

Other species, such as A. tigrinum,

- Page 497 and 498:

Metamorphosis in Insects Types of i

- Page 499 and 500:

On one side of the sac, the epithel

- Page 501 and 502:

During the first larval instar, the

- Page 503 and 504:

central region producing the Wingle

- Page 505 and 506:

The molecular biology of hydroxyecd

- Page 507 and 508:

Since its discovery in 1954, when B

- Page 509 and 510:

How do they regain the ability to d

- Page 511 and 512:

It is probable that during normal r

- Page 513 and 514:

The head activator gradient. The ab

- Page 515 and 516:

*The tradition of leaving one's boo

- Page 517 and 518:

However, recent studies have indica

- Page 519 and 520:

Moreover, if a mutation occured in

- Page 521 and 522:

Snapshot Summary: Metamorphosis, Re

- Page 523 and 524:

19. The saga of the germ line We be

- Page 525 and 526:

In the nematode C. elegans, the ger

- Page 527 and 528:

When ultraviolet light is applied t

- Page 529 and 530:

Fibronectin is likely to be an impo

- Page 531 and 532:

Germ cell migration in birds and re

- Page 533 and 534:

EG Cells, ES Cells, and Teratocarci

- Page 535 and 536:

come together and are then separate

- Page 537 and 538:

The distal tip cell extends long fi

- Page 539 and 540:

The initiation of spermatogenesis d

- Page 541 and 542:

ecause the flagellum is beginning t

- Page 543 and 544:

A partial catalogue of the material

- Page 545 and 546:

When a specific 340-base sequence f

- Page 547 and 548:

Oocyte chromosomes can be incubated

- Page 549 and 550:

The structure of the meroistic ovar

- Page 551 and 552:

Periodically, a group of primordial

- Page 553 and 554:

Following ovulation, the luteal pha

- Page 555 and 556:

20. An overview of plant developmen

- Page 557 and 558:

oth the embryo and the mature sporo

- Page 559 and 560:

*A small weed in the mustard family

- Page 561 and 562:

should provide information on the e

- Page 563 and 564:

of hormones. In scarlet runner bean

- Page 565 and 566:

embryos demonstrate that isolated p

- Page 567 and 568:

When the shoot emerges from the soi

- Page 569 and 570:

etween nodes is called an internode

- Page 571 and 572:

flowering patterns among the over 3

- Page 573 and 574:

genes, class D genes are now being

- Page 575 and 576:

Table 21.1. Specific settlement sub

- Page 577 and 578:

Predictable Environmental Differenc

- Page 579 and 580:

Diapause Many species of insects ha

- Page 581 and 582:

The hindwing pigments of the short-

- Page 583 and 584:

Ferguson and Joanen (1982) speculat

- Page 585 and 586:

Predator-Induced Defenses One survi

- Page 587 and 588:

3. Antigens are presented (usually

- Page 589 and 590:

the ipsilateral eye. The situation

- Page 591 and 592:

*The importance of substrates for l

- Page 593 and 594:

Thus, most abnormal embryos are spo

- Page 595 and 596:

Retinoic acid as a teratogen In som

- Page 597 and 598:

Another pathway to apoptosis involv

- Page 599 and 600:

Whether heavy maternal alcohol cons

- Page 601 and 602:

Some scientists, however, say that

- Page 603 and 604:

Chains of causation Whether in law

- Page 605 and 606:

Snapshot Summary: The Environmental

- Page 607 and 608:

One could emphasize the common desc

- Page 609 and 610:

The search for the Urbilaterian anc

- Page 611 and 612:

Hox Genes: Descent with Modificatio

- Page 613 and 614:

Changes in Hox gene transcription p

- Page 615 and 616:

But within the crustacean lineages,

- Page 617 and 618:

Changes in Hox gene number The numb

- Page 619 and 620:

Homologous Pathways of Development

- Page 621 and 622:

The gradient of Dpp concentration f

- Page 623 and 624:

Modularity: The Prerequisite for Ev

- Page 625 and 626:

Such a trait would be selected for

- Page 627 and 628:

*The lack of such transitional form

- Page 629 and 630:

Coevolution of ligand and receptor

- Page 631 and 632:

Evidence for this mathematical mode

- Page 633 and 634:

It is difficult for a mutation to a

- Page 635 and 636:

The population genetics model conta

- Page 637 and 638:

However, once one adds development

- Page 639 and 640:

A partial list of genes active in h