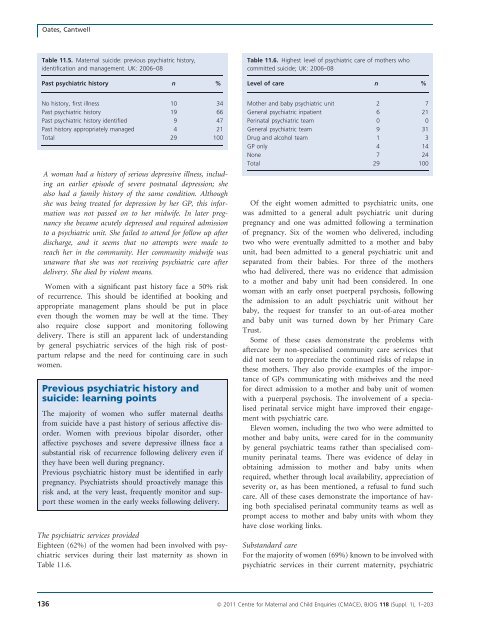

Oates, CantwellTable 11.5. Maternal suicide: previous psychiatric his<strong>to</strong>ry,identification and management. UK: <strong>2006</strong>–08Past psychiatric his<strong>to</strong>ry n %Table 11.<strong>6.</strong> Highest level of psychiatric care of mothers whocommitted suicide; UK: <strong>2006</strong>–08Level of care n %No his<strong>to</strong>ry, first illness 10 34Past psychiatric his<strong>to</strong>ry 19 66Past psychiatric his<strong>to</strong>ry identified 9 47Past his<strong>to</strong>ry appropriately managed 4 21Total 29 100A woman had a his<strong>to</strong>ry of serious depressive illness, includingan earlier episode of severe postnatal depression; shealso had a family his<strong>to</strong>ry of the same condition. Althoughshe was being treated for depression by her GP, this informationwas not passed on <strong>to</strong> her midwife. In later pregnancyshe became acutely depressed and required admission<strong>to</strong> a psychiatric unit. She failed <strong>to</strong> attend for follow up afterdischarge, and it seems that no attempts were made <strong>to</strong>reach her in the community. Her community midwife wasunaware that she was not receiving psychiatric care afterdelivery. She died by violent means.Women with a significant past his<strong>to</strong>ry face a 50% riskof recurrence. This should be identified at booking andappropriate management plans should be put in placeeven though the women may be well at the time. Theyalso require close support and moni<strong>to</strong>ring followingdelivery. There is still an apparent lack of understandingby general psychiatric services of the high risk of postpartumrelapse and the need for continuing care in suchwomen.Previous psychiatric his<strong>to</strong>ry andsuicide: learning pointsThe majority of women who suffer <strong>maternal</strong> <strong>deaths</strong>from suicide have a past his<strong>to</strong>ry of serious affective disorder.Women with previous bipolar disorder, otheraffective psychoses and severe depressive illness face asubstantial risk of recurrence following delivery even ifthey have been well during pregnancy.Previous psychiatric his<strong>to</strong>ry must be identified in earlypregnancy. Psychiatrists should proactively manage thisrisk and, at the very least, frequently moni<strong>to</strong>r and supportthese women in the early weeks following delivery.The psychiatric services providedEighteen (62%) of the women had been involved with psychiatricservices during their last maternity as shown inTable 11.<strong>6.</strong>Mother and baby psychiatric unit 2 7General psychiatric inpatient 6 21Perinatal psychiatric team 0 0General psychiatric team 9 31Drug and alcohol team 1 3GP only 4 14None 7 24Total 29 100Of the eight women admitted <strong>to</strong> psychiatric units, onewas admitted <strong>to</strong> a general adult psychiatric unit duringpregnancy and one was admitted following a terminationof pregnancy. Six of the women who delivered, includingtwo who were eventually admitted <strong>to</strong> a mother and babyunit, had been admitted <strong>to</strong> a general psychiatric unit andseparated from their babies. For three of the motherswho had delivered, there was no evidence that admission<strong>to</strong> a mother and baby unit had been considered. In onewoman with an early onset puerperal psychosis, followingthe admission <strong>to</strong> an adult psychiatric unit without herbaby, the request for transfer <strong>to</strong> an out-of-area motherand baby unit was turned down by her Primary CareTrust.Some of these cases demonstrate the problems withaftercare by non-specialised community care services thatdid not seem <strong>to</strong> appreciate the continued risks of relapse inthese mothers. They also provide examples of the importanceof GPs communicating with midwives and the needfor direct admission <strong>to</strong> a mother and baby unit of womenwith a puerperal psychosis. The involvement of a specialisedperinatal service might have improved their engagementwith psychiatric care.Eleven women, including the two who were admitted <strong>to</strong>mother and baby units, were cared for in the communityby general psychiatric teams rather than specialised communityperinatal teams. There was evidence of delay inobtaining admission <strong>to</strong> mother and baby units whenrequired, whether through local availability, appreciation ofseverity or, as has been mentioned, a refusal <strong>to</strong> fund suchcare. All of these cases demonstrate the importance of havingboth specialised perinatal community teams as well asprompt access <strong>to</strong> mother and baby units with whom theyhave close working links.Substandard careFor the majority of women (69%) known <strong>to</strong> be involved withpsychiatric services in their current maternity, psychiatric136 ª <strong>2011</strong> Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE), BJOG 118 (Suppl. 1), 1–203

Chapter 11: Deaths from psychiatric causescare was less than optimal, although in some women it maynot have affected the final outcome. Eleven women weremanaged by general adult psychiatric services and had beentreated by multiple psychiatric teams and/or had an inadequaterisk assessment. In four women, both areas of concernwere found. Another four women had a mistaken initialdiagnosis.In most women there was also evidence <strong>to</strong> suggest thatpsychiatric teams caring for the women had not appreciatedthe severity of the women’s illness, as indicated by theinitial diagnosis and the speed, level and frequency of psychiatricintervention. For example:A woman had a past his<strong>to</strong>ry of schizo-affective psychosis,and all her previous episodes were clearly related <strong>to</strong> reductionsin her medication. She had also had a previous postpartumepisode, during which she made a life-threateningsuicide attempt. She had been well on medication for manyyears, and the his<strong>to</strong>ry was identified in early pregnancy.Although she remained in close contact with psychiatric servicesthroughout her pregnancy, the maternity servicesappeared not <strong>to</strong> know how serious her past illnesses hadbeen. Following delivery she was seen frequently by a generaladult community mental health team. A few daysbefore her death, she became acutely unwell with bizarrebehaviour, delusional ideas and a preoccupation with herprevious suicide attempt. She deteriorated on a daily basis,and two more psychiatric teams were introduced in<strong>to</strong> hercare. She was then seen very frequently, but the stated aimof her management was ‘<strong>to</strong> keep her at home’. She diedfrom self immolation within a few hours of the last visit byher community nurse.This woman had a previous his<strong>to</strong>ry of a puerperal psychosisand a very serious suicide attempt. Her risk of recurrencewas high. Both her previous attempt and her currentpreoccupation with suicide placed her at high risk,increased by the rapid onset and deterioration of her conditionand a recent change in her medication. Admission<strong>to</strong> a psychiatric unit at the onset of her illness might havealtered the outcome. This is also an example of the involvemen<strong>to</strong>f multiple psychiatric teams and the lack of bothlocal specialised community perinatal mental health teamsand a mother and baby unit.Puerperal psychosis: learning pointsPuerperal psychosis (including recurrence of bipolar disorderand other affective psychoses) is relatively uncommonin daily psychiatric practice. The distinctive clinicalfeatures, including sudden onset and rapid deterioration,may be unfamiliar <strong>to</strong> nonspecialists.Psychiatric services should have a lowered threshold <strong>to</strong>intervention including admission. They should ensurecontinuity and avoid care by multiple psychiatric teams.Specialised perinatal psychiatric services, both inpatientand community, should be available.Safeguarding (child protection) social serviceinvolvementNine of the 29 women (31%) who committed suicide hadbeen referred <strong>to</strong> social services during their pregnancy,including eight of the 18 receiving psychiatric care. In fivewomen, the referral was made because the woman was apsychiatric patient rather than because of specific concernsabout the welfare of the infant. It was apparent from theirnotes that fear that the child would be removed was aprominent feature of the women’s condition and probablyled them <strong>to</strong> have difficulties in engaging with psychiatriccare:A mother who died some weeks after delivery had hadcontested cus<strong>to</strong>dy disputes over her older children. Shehad a previous his<strong>to</strong>ry of reactive depression related <strong>to</strong>her circumstances, which had been treated by the GP.Her psychological and social problems were identified inearly pregnancy, and she received excellent care from hermidwife throughout. Following delivery her midwife identifieda depressive illness, and the GP reacted promptlyand prescribed an antidepressant. She would not take thisbecause she was concerned about breastfeeding, despitethe midwife reassuring her with information from theDrug Information Service. There was excellent communicationbetween the midwife, GP and health visi<strong>to</strong>r. Someweeks later she deteriorated, and the GP urgently referredher <strong>to</strong> mental health services. At the same time she wasalso referred <strong>to</strong> the child protection service, which was‘routine in that area’. The general adult home treatmentteam found her reluctant <strong>to</strong> engage, and she was frightenedthat her children would be removed. Admission wasrecommended but declined. Shortly afterwards, she presented<strong>to</strong> the Emergency Department having swallowed acorrosive substance but did not reveal that she had alsotaken paracetamol. She was admitted <strong>to</strong> a general psychiatricunit but physically deteriorated, revealing that shehad taken an overdose of paracetamol, from which shedied shortly afterwards.This woman received excellent care from her midwifeand GP. However, it is obvious that this woman wasterrified of losing the care of her children. This fearinfluenced her cooperation with the treatments whichmight have prevented her death. A specialised communityperinatal team might have been more sensitive <strong>to</strong> theseissues.ª <strong>2011</strong> Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE), BJOG 118 (Suppl. 1), 1–203 137

- Page 1:

Volume 118, Supplement 1, March 201

- Page 4 and 5:

AcknowledgementsSaving Mothers’ L

- Page 6 and 7:

AcknowledgementsAcknowledgementsCMA

- Page 8 and 9:

Forewordbeen written jointly by a m

- Page 10 and 11:

‘Top ten’ recommendationsServic

- Page 12 and 13:

‘Top ten’ recommendationscommun

- Page 14 and 15:

‘Top ten’ recommendationsof suc

- Page 16 and 17:

‘Top ten’ recommendationsMarch

- Page 18 and 19:

Oates et al.Back to basicsM Oates 1

- Page 20 and 21:

Oates et al.BreathlessnessBreathles

- Page 22 and 23:

Oates et al.appropriate pathway of

- Page 24 and 25:

LewisIntroduction: Aims, objectives

- Page 26 and 27:

LewisAn important limitation of ran

- Page 28 and 29:

Lewismaternal and public health-pol

- Page 30 and 31:

Lewisresult in a live birth at any

- Page 32 and 33:

LewisChapter 1: The women who died

- Page 34 and 35:

Lewiswho would not have been identi

- Page 36 and 37:

Lewis1098Rate per 100 000 materniti

- Page 38 and 39:

LewisTable 1.4. Numbers and rates o

- Page 40 and 41:

Lewis2.50Rate per 100 000 materniti

- Page 42 and 43:

LewisTable 1.9. Number of maternal

- Page 44 and 45:

LewisTable 1.12. Numbers and percen

- Page 46 and 47:

LewisThere were cases where a major

- Page 48 and 49:

LewisBox 1.5. Classifications of Bo

- Page 50 and 51:

LewisTable 1.20. Number and estimat

- Page 52 and 53:

LewisNew countries of the European

- Page 54 and 55:

LewisTable 1.23. Direct and Indirec

- Page 56 and 57:

LewisTable 1.26. Characteristics* o

- Page 58 and 59:

Lewis4 Lewis G (ed). The Confidenti

- Page 60 and 61:

DrifeTable 2.1. Direct deaths from

- Page 62 and 63:

Drifewomen who died in 2006-08 had

- Page 64 and 65:

Drifedelivery she became breathless

- Page 66 and 67:

DrifePathological overviewFourteen

- Page 68 and 69:

NeilsonChapter 3: Pre-eclampsia and

- Page 70 and 71:

Neilsontrue, and what might be the

- Page 72 and 73:

NeilsonConclusionThe number of deat

- Page 74 and 75:

NormanBackgroundIn the UK, major ob

- Page 76 and 77:

Normanwhich there was catastrophic

- Page 78 and 79:

Normanrecommendations made in succe

- Page 80 and 81:

DawsonBox 5.1. The UK amniotic flui

- Page 82 and 83:

Dawsontry despite an extensive sear

- Page 84 and 85:

O’HerlihyTable 6.1. Numbers of Di

- Page 86 and 87:

O’Herlihytoxic shock syndrome aft

- Page 88 and 89: HarperGroup A b-haemolytic streptoc

- Page 90 and 91: Harperthe 6-week postnatal period,

- Page 92 and 93: Harpera major intrapartum haemorrha

- Page 94 and 95: HarperBox 7.1. Signs and symptoms o

- Page 96 and 97: Harperwoman was given several litre

- Page 98 and 99: Harper2 Lamagni TL, Efstratiou A, D

- Page 100 and 101: LucasTable A7.1 Proposed new catego

- Page 102 and 103: Lucasthe same infection scenario as

- Page 104 and 105: McClure, CooperChapter 8: Anaesthes

- Page 106 and 107: McClure, Cooperaddress, but protoco

- Page 108 and 109: McClure, CooperPostpartum haemorrha

- Page 110 and 111: McClure, CooperWorkloadA number of

- Page 112 and 113: Nelson-PiercyTable 9.1. Indirect ma

- Page 114 and 115: Nelson-Piercynary arteries. In view

- Page 116 and 117: Nelson-Piercynormal left ventricle

- Page 118 and 119: LucasAnnex 9.1. Pathological overvi

- Page 120 and 121: Lucasdiac death that is non-ischaem

- Page 122 and 123: de Swiet et al.causes but are aggra

- Page 124 and 125: de Swiet et al.died of SUDEP before

- Page 126 and 127: de Swiet et al.for 6 weeks after de

- Page 128 and 129: de Swiet et al.mised. The obstetric

- Page 130 and 131: de Swiet et al.CancerPregnancy does

- Page 132 and 133: de Swiet et al.a thorough autopsy w

- Page 134 and 135: Oates, CantwellChapter 11: Deaths f

- Page 136 and 137: Oates, CantwellTable 11.1. Timing o

- Page 140 and 141: Oates, CantwellChild protection iss

- Page 142 and 143: Oates, CantwellAll women who are su

- Page 144 and 145: Oates, Cantwell4 Kendel RE, Chalmer

- Page 146 and 147: Lewismaternal mortality rates or ra

- Page 148 and 149: Annex 12.1. Domestic abuseAnnex 12.

- Page 150 and 151: Annex 12.1. Domestic abuseshe could

- Page 152 and 153: Garrod et al.supportive but challen

- Page 154 and 155: Garrod et al.• Culture and system

- Page 156 and 157: Garrod et al.the second stage and s

- Page 158 and 159: Garrod et al.through the still heal

- Page 160 and 161: ShakespeareChapter 14: General prac

- Page 162 and 163: Shakespeareemergency caesarean sect

- Page 164 and 165: ShakespeareCardiac diseaseDeaths fr

- Page 166 and 167: Shakespearereduce the risks to the

- Page 168 and 169: ShakespeareManaging a maternal deat

- Page 170 and 171: Hulbertin the ED was of a high qual

- Page 172 and 173: HulbertPre-eclampsia/eclampsia: lea

- Page 174 and 175: HulbertTransfersWhen the obstetric

- Page 176 and 177: Clutton-Brocksimply the case that s

- Page 178 and 179: Clutton-BrockDiagnosis of sepsisTak

- Page 180 and 181: Clutton-Brockpulseless electrical a

- Page 182 and 183: Clutton-BrockImprovement Scotland (

- Page 184 and 185: Lucas, Millward-Sadler95 mmHg. This

- Page 186 and 187: Lucas, Millward-Sadleran agreed mai

- Page 188 and 189:

Annex 17.1. The main clinico-tholog

- Page 190 and 191:

MillerAppendix 1: The method of Enq

- Page 192 and 193:

MillerDatanotificationNotificationR

- Page 194 and 195:

Knight• investigating different m

- Page 196 and 197:

Knightbaseline incidence against wh

- Page 198 and 199:

LennoxAppendix 2B: Summary of Scott

- Page 200 and 201:

LennoxEvidence of effective managem

- Page 202 and 203:

Appendix 3: Contributors to the Mat

- Page 204 and 205:

Appendix 3: Contributors to the Mat