A decade later - Fundação Luso-Americana

A decade later - Fundação Luso-Americana

A decade later - Fundação Luso-Americana

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

54<br />

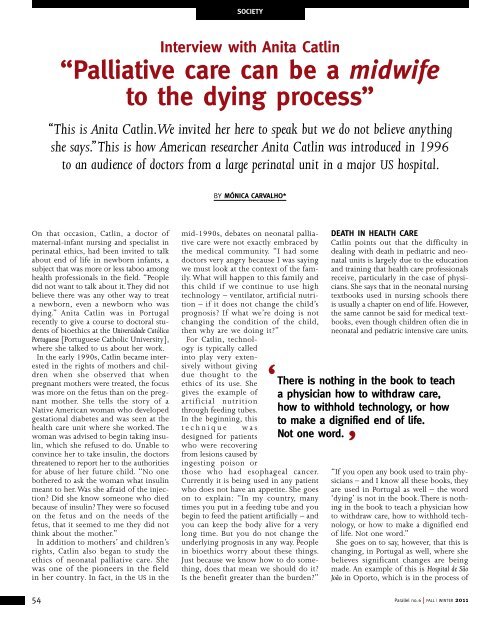

socieTy<br />

interview with Anita catlin<br />

“palliative care can be a midwife<br />

to the dying process”<br />

“This is Anita Catlin. We invited her here to speak but we do not believe anything<br />

she says.” This is how American researcher Anita Catlin was introduced in 1996<br />

to an audience of doctors from a large perinatal unit in a major US hospital.<br />

On that occasion, Catlin, a doctor of<br />

maternal-infant nursing and specialist in<br />

perinatal ethics, had been invited to talk<br />

about end of life in newborn infants, a<br />

subject that was more or less taboo among<br />

health professionals in the field. “People<br />

did not want to talk about it. They did not<br />

believe there was any other way to treat<br />

a newborn, even a newborn who was<br />

dying.” Anita Catlin was in Portugal<br />

recently to give a course to doctoral students<br />

of bioethics at the Universidade Católica<br />

Portuguesa [Portuguese Catholic University],<br />

where she talked to us about her work.<br />

In the early 1990s, Catlin became interested<br />

in the rights of mothers and children<br />

when she observed that when<br />

pregnant mothers were treated, the focus<br />

was more on the fetus than on the pregnant<br />

mother. She tells the story of a<br />

Native American woman who developed<br />

gestational diabetes and was seen at the<br />

health care unit where she worked. The<br />

woman was advised to begin taking insulin,<br />

which she refused to do. Unable to<br />

convince her to take insulin, the doctors<br />

threatened to report her to the authorities<br />

for abuse of her future child. “No one<br />

bothered to ask the woman what insulin<br />

meant to her. Was she afraid of the injection?<br />

Did she know someone who died<br />

because of insulin? They were so focused<br />

on the fetus and on the needs of the<br />

fetus, that it seemed to me they did not<br />

think about the mother.”<br />

In addition to mothers’ and children’s<br />

rights, Catlin also began to study the<br />

ethics of neonatal palliative care. She<br />

was one of the pioneers in the field<br />

in her country. In fact, in the US in the<br />

By mónicA cArvALHo*<br />

mid-1990s, debates on neonatal palliative<br />

care were not exactly embraced by<br />

the medical community. “I had some<br />

doctors very angry because I was saying<br />

we must look at the context of the family.<br />

What will happen to this family and<br />

this child if we continue to use high<br />

technology – ventilator, artificial nutrition<br />

– if it does not change the child’s<br />

prognosis? If what we’re doing is not<br />

changing the condition of the child,<br />

then why are we doing it?”<br />

For Catlin, technology<br />

is typically called<br />

into play very extensively<br />

without giving<br />

due thought to the<br />

ethics of its use. She<br />

gives the example of<br />

artificial nutrition<br />

through feeding tubes.<br />

In the beginning, this<br />

t e c h n i q u e w a s<br />

designed for patients<br />

who were recovering<br />

from lesions caused by<br />

ingesting poison or<br />

those who had esophageal cancer.<br />

Currently it is being used in any patient<br />

who does not have an appetite. She goes<br />

on to explain: “In my country, many<br />

times you put in a feeding tube and you<br />

begin to feed the patient artificially – and<br />

you can keep the body alive for a very<br />

long time. But you do not change the<br />

underlying prognosis in any way. People<br />

in bioethics worry about these things.<br />

Just because we know how to do something,<br />

does that mean we should do it?<br />

Is the benefit greater than the burden?”<br />

deATH in HeALTH cAre<br />

Catlin points out that the difficulty in<br />

dealing with death in pediatric and neonatal<br />

units is largely due to the education<br />

and training that health care professionals<br />

receive, particularly in the case of physicians.<br />

She says that in the neonatal nursing<br />

textbooks used in nursing schools there<br />

is usually a chapter on end of life. However,<br />

the same cannot be said for medical textbooks,<br />

even though children often die in<br />

neonatal and pediatric intensive care units.<br />

‘ There is nothing in the book to teach<br />

a physician how to withdraw care,<br />

how to withhold technology, or how<br />

to make a dignified end of life.<br />

not one word.<br />

’<br />

“If you open any book used to train physicians<br />

– and I know all these books, they<br />

are used in Portugal as well – the word<br />

‘dying’ is not in the book. There is nothing<br />

in the book to teach a physician how<br />

to withdraw care, how to withhold technology,<br />

or how to make a dignified end<br />

of life. Not one word.”<br />

She goes on to say, however, that this is<br />

changing, in Portugal as well, where she<br />

believes significant changes are being<br />

made. An example of this is Hospital de São<br />

João in Oporto, which is in the process of<br />

Parallel no. 6 | FALL | WINTER 2011