VOLUME 1 HUMAN SETTLEMENT PLANNING AND ... - CSIR

VOLUME 1 HUMAN SETTLEMENT PLANNING AND ... - CSIR

VOLUME 1 HUMAN SETTLEMENT PLANNING AND ... - CSIR

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

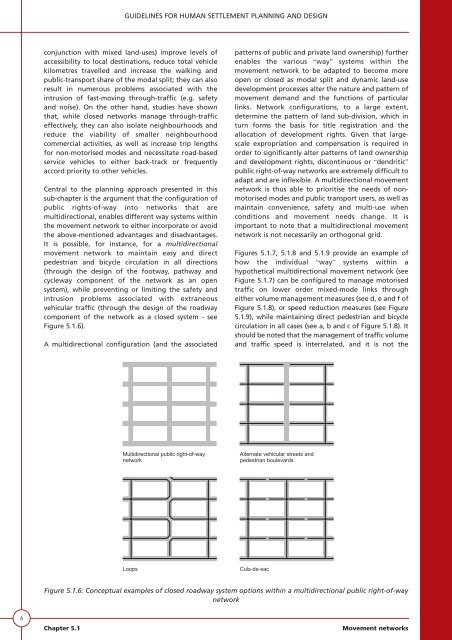

GUIDELINES FOR <strong>HUMAN</strong> <strong>SETTLEMENT</strong> <strong>PLANNING</strong> <strong>AND</strong> DESIGNconjunction with mixed land-uses) improve levels ofaccessibility to local destinations, reduce total vehiclekilometres travelled and increase the walking andpublic-transport share of the modal split; they can alsoresult in numerous problems associated with theintrusion of fast-moving through-traffic (e.g. safetyand noise). On the other hand, studies have shownthat, while closed networks manage through-trafficeffectively, they can also isolate neighbourhoods andreduce the viability of smaller neighbourhoodcommercial activities, as well as increase trip lengthsfor non-motorised modes and necessitate road-basedservice vehicles to either back-track or frequentlyaccord priority to other vehicles.Central to the planning approach presented in thissub-chapter is the argument that the configuration ofpublic rights-of-way into networks that aremultidirectional, enables different way systems withinthe movement network to either incorporate or avoidthe above-mentioned advantages and disadvantages.It is possible, for instance, for a multidirectionalmovement network to maintain easy and directpedestrian and bicycle circulation in all directions(through the design of the footway, pathway andcycleway component of the network as an opensystem), while preventing or limiting the safety andintrusion problems associated with extraneousvehicular traffic (through the design of the roadwaycomponent of the network as a closed system - seeFigure 5.1.6).A multidirectional configuration (and the associatedpatterns of public and private land ownership) furtherenables the various “way” systems within themovement network to be adapted to become moreopen or closed as modal split and dynamic land-usedevelopment processes alter the nature and pattern ofmovement demand and the functions of particularlinks. Network configurations, to a large extent,determine the pattern of land sub-division, which inturn forms the basis for title registration and theallocation of development rights. Given that largescaleexpropriation and compensation is required inorder to significantly alter patterns of land ownershipand development rights, discontinuous or “dendritic”public right-of-way networks are extremely difficult toadapt and are inflexible. A multidirectional movementnetwork is thus able to prioritise the needs of nonmotorisedmodes and public transport users, as well asmaintain convenience, safety and multi-use whenconditions and movement needs change. It isimportant to note that a multidirectional movementnetwork is not necessarily an orthogonal grid.Figures 5.1.7, 5.1.8 and 5.1.9 provide an example ofhow the individual “way” systems within ahypothetical multidirectional movement network (seeFigure 5.1.7) can be configured to manage motorisedtraffic on lower order mixed-mode links througheither volume management measures (see d, e and f ofFigure 5.1.8), or speed reduction measures (see Figure5.1.9), while maintaining direct pedestrian and bicyclecirculation in all cases (see a, b and c of Figure 5.1.8). Itshould be noted that the management of traffic volumeand traffic speed is interrelated, and it is not theMultidirectional public right-of-waynetworkAlternate vehicular streets andpedestrian boulevardsLoopsCuls-de-sacFigure 5.1.6: Conceptual examples of closed roadway system options within a multidirectional public right-of-waynetwork6Chapter 5.1Movement networks