<strong>Herpetological</strong> <strong>Review</strong>, 2008, 39(2), 156–162.© 2008 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and ReptilesBody-flip and Immobility Behavior in RegalHorned Lizards: A Gape-limiting DefenseSelectively Displayed Toward One of Two SnakePredatorsWADE C. SHERBROOKESouthwestern Research Station, American Museum of Natural HistoryPortal, Arizona 85632, USAe-mail: wcs@amnh.organdCLAYTON J. MAY5814 South Hopdown Lane, Tucson, Arizona 85746, USAIn 1937 Howard K. Gloyd led a herpetological expedition tosouthern Arizona (Gloyd 1937). Film records show a body-flippingreaction, termed “plays dead,” of a Regal Horned Lizard(Phrynosoma solare) to prodding with a thin stick and subsequenthuman handling. An adult lizard repeatedly flipped itself onto itsback, nine times within 25 s (immediately righted by Gloyd’s handafter each flip). We found only one subsequent mention of thebehavior in P. solare, without functional explanation (Parker 1971).Death feigning, letisimulation, or tonic immobility, has beenconsidered an antipredator response across invertebrate and vertebratetaxa without clear identification of its adaptive significance(Carpenter and Ferguson 1977; Greene 1994; Honma et al. 2006;Ruxton 2006; Ruxton et al. 2004), although in some predatoryfish the use of death feigning appears to be clearly adaptive duringaggressive mimicry (Tobler 2005). Many hypotheses offeredto explain immobility responses of prey tacitly assume that preymanipulate predators by sending false information that they aredead and that this information interrupts prey-subjugation behaviors,thus providing opportunities for prey escape (Honma et al.2006; Ruxton 2006). Honma et al. (2006) proposed that an inducibledeath-feigning response of a pygmy grasshopper (Criotettixjaponicus) is a specific antipredator response against a gape-limitedanuran predator to avoid being swallowed. The grasshopper’scharacteristic rigid posture, with body parts physically extended,interferes with prey manipulation and does not mimic death, butdirectly enhances prey survival.In the case of P. solare, it is difficult to identify an evolutionarilyadaptive advantage to body-flipping and re-flipping, to upside-down,by an immobile, death-feigning, animal. This leavesthe behavior lacking a clear biological explanation. Our study attemptsto place body-flipping and immobility behavior by P. solarein the context of adaptive antipredator behaviors that are effectiveresistance against specific predators that rely on jaw capture ofprey which they ingest whole, such as a non-venomous snake.We report several additional encounters (rare) of body-flippingbehavior in P. solare in response to human handling. We then describefield trials aimed at elicitation of the body-flipping andimmobility response or alternative responses (such as runningflight) in specific predator-context encounters involving twosnakes, one non-venomous (Masticophis flagellum) and one venomous(Crotalus atrox). The two snakes present the lizards withtwo different threats based on their prey-subjugation strategies(Endler 1991; Sherbrooke 2008), 1) M. flagellum: search/wait,identify, rapidly pursue, physically jaw-capture, subjugate, andingest, and 2) C. atrox: wait, identify, envenomate (strike), track,and ingest carcass. We use our observations to propose that thelizards distinguish between two categories of predator threat, thetwo snakes, and respond to each with distinctive antipredator behaviors(flipping or running) that appear appropriate for selectivelyenhancing survival in response to each predator’s subjugationskills. We also use the differences in responses of P. solare tothe two snakes to propose a hypothesis for the previously unexplainedbody-flipping and immobility behavior, noting the predatorcontexts in which it is employed and not employed, and wediscuss aspects of body-flipping and immobility that may functionas antipredation defenses with M. flagellum.METHODSCarpenter and Ferguson (1977) reviewed literature reports andnumerically catalogued lizard behaviors (termed “act systems”)involving body inversion (act system #26, turn over) andletisimulation (act system #150) in various lineages oflepidosaurians. Similarly, Greene (1994) enumerated several categoriesof antipredator behaviors (#3, catalepsy, letisimulation,death feigning, tonic immobility; #22, invert body). It is difficultto unequivocally assign our observations to a particular categorydue to the paucity of examples, diversity of descriptions, and frequentlack of meaningful context for the reported behaviors. Wesimply use descriptive terms, body-flip and immobility behavior.In a body-flip followed by immobility a lizard rapidly raises oneside (by extending its legs on that side) to effect a role over alongits nose-to-vent axis, landing upside down where it remains motionless(see Figs. 1 and 2).Following an observation of repeated body-flipping and immobilityof a captive P. solare in response to human handling (Fig. 1,A–C; 30 June 2006), we reviewed our field notes and summarizedadditional records of this behavior.We then studied the behavioral responses of adult P. solare duringfield trials utilizing a known ophidian predator of P. solare,the Coachwhip (M. flagellum) (Kauffeld 1957), that also preys onother similarly-armored horned lizards (Sherbrooke 1981). Theindividual M. flagellum (SVL 128 cm, tail length [TL] 47 cm;mass 787 g) utilized had previously been observed to capture andeat a P. solare (SVL 88 mm, TL 48 mm; mass 36.4 g) on the studyarea (May, unpubl. data). Our trials involved four P. solare fittedwith radio-transmitters (Holohil PD-2; approximately 3 g), whichwere relocated in the field, and six lizards encountered in situ whiletraversing the study area. Fourteen trials, involving 52 encounters(presentations), occurred between 26 August and 2 September 2006(Table 1): 0930–1200 h MST (12), and 1730–1900 h MST (2).The study area is immediately adjacent, on the west and northwestsides, to a small volcanic hill in the Altar Valley, Pima Co.,Arizona (32°02'11.5"N, 111°23'46.6"W, datum WGS 384).During trial encounters, the M. flagellum was restrained in glovedhands at mid-body, allowing the anterior third or more to movefreely as it was held to the ground approximately 1 m from thelizards. It was then allowed/encouraged to approach and contacteach lizard (Fig. 2, A). During each trial, an attempt was made toexpose the lizard four times to the snake. Contact by the snake156 <strong>Herpetological</strong> <strong>Review</strong> 39(2), 2008

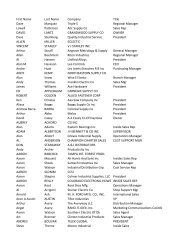

TABLE 1. Summary of behaviors exhibited by ten Regal Horned Lizards (Phrynosoma solare) in response to approach of a Coachwhip (Masticophisflagellum) in 14 trials involving 52 staged encounters (usually 4/trial). For runs, specific encounter numbers (1–4) are identified. Encounter data aresummarized, including number of tilts/trial and the distance (estimated ranges in dm; distance data not complete for lizards #3 26 August, and # 7) ofthe snake when initiated, occurrence of horn raising by the lizard, and number of encounters in which the snake effected tactile contact, or not, with thelizard. In addition, for encounters of each trial, the mean time and range of the lizard remaining in a flipped position for encounters of each trial arepresented.Lizard # Sex SVL Lizard Lizard Tilt #/s Horns Snake FlipTrial — Date (mm) body-flip run distance raised contact mean/rangeencounters encounters (range, (+ / –) (+ / –) (s)/trial /trial, (#) dm)1— 26 Aug F 96 0 1 (1 st ) 0/— 0/1 0/11— 2 Sept 4 0 4/1–2 0/4 3/1 52/11–1062— 26 Aug F 95 4 0 4/3–4 4/0 4/0 33/23–422— 2 Sept 4 0 4/0.5–2 0/4 3/1 92/43–1233— 26 Aug F 100 4 0 4/3 2/2 4/0 21/15–393— 2 Sept 4 0 4/0.5–1 1/3 3/1 36/19–494— 26 Aug M 88 4 0 4/3–4 4/0 3/1 48/35–714— 2 Sept 2 1 (3 rd ) 3/3–4 0/3 2/1 6.5/5–85— 28 Aug F 91 4 0 4/2–5 3/1 4/0 17/6–286— 27 Aug F 109 3 1 (2 nd ) 4/2–5 3/1 3/1 28/6–517— 26 Aug M 89 4 0 4/0.5–7 1/3 3/1 14/3–198— 26 Aug M 82 4 0 4/2–3 4/0 4/0 21/3–419— 31 Aug M 93 4 0 4/1–5 2/2 4/0 32/12–6010— 1 Sept F 97 3 1 (4 th ) 4/1–3 0/4 3/1 4/2–7Totals 14 48 4 51/0.5–7 24/28 43/9 n = 46(present +, or absent –) prior to a lizard response (body-flip orrun) was noted. Following a lizard response, the snake was withdrawnand hidden from view behind the experimenter. A subsequentencounter was initiated within about 1 min of the lizard’srighting itself. Reactions of the lizards were noted: distance atwhich body tilting (dorso-ventral flattening of the abdomen whileraising one side and lowering the opposite side, as in “dorsalshield;” Sherbrooke 2008) toward the snake occurred, body-flipping,time lizards spent resting on dorsum following flipping beforeself-righting, eyelids (opened or closed), eyelid bulging(present or absent), horns raised (executed +, or not – ; Sherbrooke1987), color change (effected or not, and resulting color), runningescape (if employed, distance). For each trial, a range of the fourencounters is given for the distance at which the lizard began exhibitingtilt behavior (except in trials with fewer encounters, Table1).On 14 September 2006 we studied, in a similar fashion (Table2) and at the same field site noted above, the behavioral responsesof adult P. solare to a known venomous ophidian predator, theWestern Diamond-backed Rattlesnake (C. atrox) (Vorhies 1948),which also preys on other horned lizards (Sherbrooke 2003, unpubl.data). The snake was collected west of the Tucson Mountains, AvraValley, Pima Co. Tucson, Arizona (32°11'09.5"N, 111°05'58.9"W).The snake (SVL 82 cm, TL 8 cm; mass 385 g) was placed in a 46cm long clear plastic tube of 3.5 cm diameter. The snake’s headand fore-body extended 15 cm from one end of the tube (Fig. 2C),and the tail extended from the opposite end. The apparatus, withsnake, was hand held at the tube base where the posterior extendingportion of the snake was duct-taped to the tube rim to ensure agrip of adherence to the snake’s body scales without undue constriction,thus preventing forward movement in the tube. The tubedsnake, safely and not aggressively restricted in its movements,was held with its head extended during encounters.Trial encounters were conducted between 0900–1100 h MST,with five lizards (including the four radiotagged lizards) havinghad previous encounters with M. flagellum. The other three lizards(#s 1, 2, 7) had no previous experimental contact with snakes.The radiotagged lizards were located and tested where found inthe field. The other four lizards had previously been captured andbriefly maintained (3–8 days) in outdoor enclosures (fed and watered)before release back at their field capture sites, where theywere subjected to our trial encounters.The eight lizards were exposed to C. atrox in a total of 24 encounters(presentations), which varied between two and six dependingon the outcome of encounters. Similar to the Masticophisencounters, the rattlesnake’s fore-body was placed on the groundnear the lizard and moved toward the lizard until it was withinattack distance. The anterior portion of the snake extending fromthe tube moved freely as the snake explored its surroundings. Lizardsthat ran were followed and the snake was again presented tothe lizard, usually within a minute of it having stopped.RESULTSBody-flip responses to human stimuli.—Incidental to other studiesthat involved capture of hundreds of P. solare over the years<strong>Herpetological</strong> <strong>Review</strong> 39(2), 2008 157

- Page 1 and 2: HerpetologicalReviewVolume 39, Numb

- Page 3 and 4: About Our Cover: Zonosaurus maramai

- Page 5 and 6: Prey-specific Predatory Behavior in

- Page 7 and 8: acid water treatment than in the co

- Page 10 and 11: TABLE 1. Time-line history of croco

- Page 12 and 13: The Reptile House at the Bronx Zoo

- Page 14 and 15: FIG. 6. A 3.9 m (12' 11 1 / 2") Ame

- Page 16 and 17: One of the earliest studies of croc

- Page 18 and 19: TABLE 2. Dimensions and water depth

- Page 20 and 21: we call it, is in flux.Forty years

- Page 22 and 23: Feb. 20-25. abstract.------. 1979.

- Page 24 and 25: yond current practices (Clarke 1972

- Page 26 and 27: poles (Pond 1 > 10,000, Pond 2 4,87

- Page 28 and 29: ------, R. MATHEWS, AND R. KINGSING

- Page 32 and 33: TABLE 2. Summary of running (includ

- Page 34 and 35: FIG. 2. Responses of adult Regal Ho

- Page 36 and 37: PIANKA, E. R., AND W. S. PARKER. 19

- Page 38 and 39: BUSTAMANTE, M. R. 2005. La cecilia

- Page 40 and 41: Fig. 3. Mean clutch size (number of

- Page 42 and 43: facilitated work in Thailand. I tha

- Page 44 and 45: preocular are not fused. The specim

- Page 46 and 47: FIG. 2A) Side view photo of Aechmea

- Page 48 and 49: 364.DUELLMAN, W. E. 1978. The biolo

- Page 50 and 51: incision, and placed one drop of Ba

- Page 52 and 53: 13 cm deep (e.g., Spea hammondii; M

- Page 54 and 55: FIG. 1. Medicine dropper (60 ml) wi

- Page 56 and 57: esearchers and Hellbenders, especia

- Page 58 and 59: FIG. 3. Relative success of traps p

- Page 60 and 61: data on Hellbender population struc

- Page 62 and 63: aits sometimes resulted in differen

- Page 64 and 65: trapping system seems to be a relat

- Page 66 and 67: AMPHIBIAN CHYTRIDIOMYCOSISGEOGRAPHI

- Page 68 and 69: TABLE 1. Prevalence of B. dendrobat

- Page 70 and 71: Conservation Status of United State

- Page 72 and 73: TABLE 1. Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica)

- Page 74 and 75: TABLE 1. Anurans that tested positi

- Page 76 and 77: is, on average, exposed to slightly

- Page 78 and 79: (10%) were dead but not obviously m

- Page 80 and 81:

Submitted by CHRIS T. McALLISTER, D

- Page 82 and 83:

FIG. 1. Oscillogram, spectrogram, a

- Page 84 and 85:

FIG. 1. Adult Physalaemus cuvieri r

- Page 86 and 87:

Répteis, Instituto Nacional de Pes

- Page 88 and 89:

discovered 145 live hatchlings and

- Page 90 and 91:

GRAPTEMYS GIBBONSI (Pascagoula Map

- Page 92 and 93:

College, and the Joseph Moore Museu

- Page 94 and 95:

FIG. 1. Common Ground Lizard (Ameiv

- Page 96 and 97:

havior unavailable elsewhere. Here

- Page 98 and 99:

15% of predator mass, is typical fo

- Page 100 and 101:

side the third burrow and began a f

- Page 102 and 103:

We thank Arlington James and the st

- Page 104 and 105:

mm) S. viridicornis in its mouth in

- Page 106 and 107:

NECTURUS MACULOSUS (Common Mudpuppy

- Page 108 and 109:

LITHOBATES CATESBEIANUS (American B

- Page 110 and 111:

Research and Collections Center, 13

- Page 112 and 113:

BRONCHOCELA VIETNAMENSIS (Vietnam L

- Page 114 and 115:

Oficina Regional Guaymas, Guaymas,

- Page 116 and 117:

MICRURUS TENER (Texas Coralsnake).

- Page 118 and 119:

declining in this recently discover

- Page 120 and 121:

80.7372°W). 02 November 2005. Stev

- Page 122 and 123:

this effort, 7% of the 10 × 10 km

- Page 124 and 125:

the knowledge of the group. The aut

- Page 126 and 127:

which is listed under “Rhodin, A.

- Page 128 and 129:

noting that Sphenomorphus bignelli

- Page 130 and 131:

256 Herpetological Review 39(2), 20

- Page 132:

ISSN 0018-084XThe Official News-Jou