TABLE 1. Anurans that tested positive or negative for the presence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in Denmark in 2007. See Fig. 1 for thelocations of the study areas referenced in the table. The species examined were Rana kl. esculenta (RANESC), and Rana temporaria (RANTEM).StudyArea Latitude Longitude Species Stage Sex No. Positive No. NegativeEgense 55.044167 10.519444 RANTEM adult unknown 1 3Amtoft 57.007500 8.939722 RANTEM adult male 0 1Klosterheden 56.485278 8.362500 RANTEM juvenile unknown 0 1Vestamager 55.614722 12.577222 RANESC adult male 0 3Vestamager 55.614722 12.577222 RANESC adult female 0 1Vestamager 55.614722 12.577222 RANESC juvenile unknown 1 2Further surveys should be undertaken to determine the extent ofthe pathogen in Denmark. In the meantime, proper sanitizing ofequipment would be prudent for anyone entering amphibian habitats.Particular care should be used around sensitive species suchas Bombina bombina, which is actively managed in Denmark (Pihlet al. 2001), however the threat posed by B. dendrobatidis to thisand other Danish species is currently unknown.Acknowledgments.—These surveys were authorized by The Danish Forestand Nature Agency of the Ministry of the Environment with letter of15 January 2008 (SNS-441-00088). No chemicals or other substanceswere used on the body of the amphibians and all criteria for the humancare of captured animals were followed. Use of trade names does notconstitute endorsement.LITERATURE CITEDANNIS, S.L., F.P. DASTOOR, H. ZIEL, P. DASZAK, AND J.E. LONGCORE. 2004.A DNA-based assay identifies Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis inamphibians. J. Wild. Dis. 40:420–428.BERGER, L., R. SPEARE, P. DASZAK, D. E. GREEN, A. A. CUNNINGHAM, C. L.GOGGIN, R. SLOCOMBE, M. A. RAGAN, A. D. HYATT, K. R. MCDONALD, H.B. HINES, K. R. LIPS, G. MARANTELLI, AND H. PARKES. 1998.Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with populationdecline in the rain forests of Australia and Central America. Proc.Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9031–9036.CUNNINGHAM, A.A., T.W.J. GARNER, V. ANGUILAR-SANCHEZ, B. BANKS, J.FOSTER, A.W. SAINSBURY, M. PERKINS, S.F. WALKER, A.D. HYATT, ANDM.C. FISHER. 2005. The emergence of amphibian chytridiomycosis inBritain. Vet. Rec. 157: 386–387.GARNER, T.W.J., M. PERKINS, P. GOVINDARAJULU, D. SEGLIE, S.J. WALKER,A.A. CUNNINGHAM, AND M.C. FISHER. 2006. The emerging amphibianpathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis globally infects introducedpopulations of the North American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana. Biol.Lett. 2:455–459.––––––, S. WALKER, J. BOSCH, A. D. HYATT, A. A. CUNNINGHAM, AND M. C.FISHER. 2005. Chytrid fungus in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1639–1641.MUTSCHMANN, F., L. BERGER, P. ZWART, AND C. GAEDICKE. 2000.Chytridiomycosis in amphibians—first report in Europe. Berl. Munch.Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 113:380–383.OUELLET, M., I. MIKAELIAN, B. D. PAULI, J. RODRIGUE, AND D. M. GREEN.2005. Historical evidence of widespread chytrid infection in NorthAmerican amphibian populations. Conserv. Biol. 19:1431–1440.PIHL, S., R., EJRNÆS, B. SØGAARD, E. AUDE, K.E. NIELSEN, K. DAHL. ANDJ.S. LAURSEN. 2001. Habitats and species covered by the EEC HabitatsDirective: a preliminary assessment of distribution and conservationstatus in Denmark. NERI Technical Report No. 365. NationalEnvironmental Research Institute, Denmark. 121 pp.SIMONCELLI, F., A. FAGOTTI, R. DALL’OLIO, D. VAGNETTI, R. PASCOLINI, ANDI. DI ROSA. 2005. Evidence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis infectionin water frogs of the Rana esculenta complex in central Italy. EcoHealth2:307–312.SKERRATT, L. F., L. BERGER, R. SPEARE, S. CASHINS, K. R. MCDONALD, A.D. PHILLOTT, H. B. HINES, AND N. KENYON. 2007. Spread ofchytridiomycosis has caused the rapid global decline and extinction offrogs. EcoHealth 4:125–134.STAGNI G., R. DALL’OLIO, U. FUSINI, S. MAZZOTTI, C. SCOCCIANTI, AND A.SERRA. 2004. Declining populations of Apennine yellow-bellied toadBombina pachypus in northern Apennines, Italy: is Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis the main cause? Ital. J. Zool. Suppl. 2:151–154.STUART, S.N., J.S. CHANSON, N.A. COX, B.E. YOUNG, A.S.L. RODRIGUES,D.L. FISCHMAN, AND R.W. WALTER. 2004. Status and trends of amphibiandeclines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306:1783–1786.<strong>Herpetological</strong> <strong>Review</strong>, 2008, 39(2), 200–202.© 2008 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and ReptilesBatrachochytrium dendrobatidis Not Detected inOophaga pumilio on Bastimentos Island, PanamaCORINNE L. RICHARDS *AMANDA J. ZELLMERandLISA M. MARTENSDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary BiologyandMuseum of Zoology, University of Michigan, 1109 Geddes AvenueAnn Arbor, Michigan 48109-1079, USA*Corresponding author; e-mail: clrichar@umich.eduAmphibian chytridiomycosis, caused by the chytrid fungusBatrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), has been implicated in thedecline and extinction of many populations worldwide (Berger etal. 1998; Lips et al. 2006; Skerratt et al. 2007), and has led tomassive die-offs in Latin America over the past few decades (Lipset al. 2006). However, not all populations that carry Bd have experiencedsuch declines (e.g., American Bullfrog: Garner et al.2006; African Clawed Frog: Weldon et al. 2004). Some specieshave been shown to have physiological (Woodhams et al. 2007a),behavioral (C.L. Richards, pers. comm.), or bacterial (Woodhamset al. 2007b) defenses that may allow them to cope with Bd. Formany species that have not experienced declines, it is unknown200 <strong>Herpetological</strong> <strong>Review</strong> 39(2), 2008

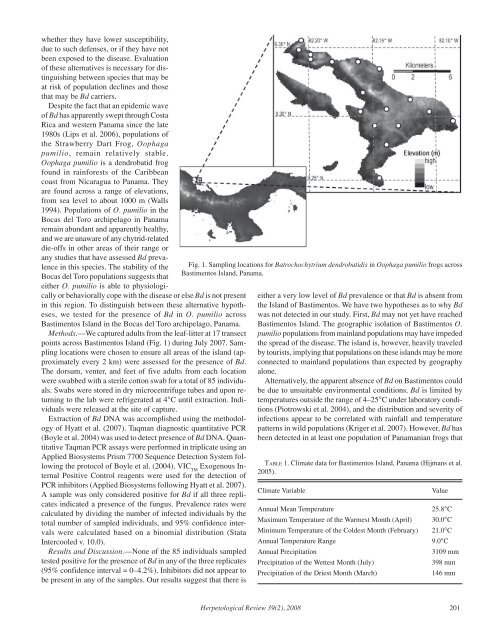

whether they have lower susceptibility,due to such defenses, or if they have notbeen exposed to the disease. Evaluationof these alternatives is necessary for distinguishingbetween species that may beat risk of population declines and thosethat may be Bd carriers.Despite the fact that an epidemic waveof Bd has apparently swept through CostaRica and western Panama since the late1980s (Lips et al. 2006), populations ofthe Strawberry Dart Frog, Oophagapumilio, remain relatively stable.Oophaga pumilio is a dendrobatid frogfound in rainforests of the Caribbeancoast from Nicaragua to Panama. Theyare found across a range of elevations,from sea level to about 1000 m (Walls1994). Populations of O. pumilio in theBocas del Toro archipelago in Panamaremain abundant and apparently healthy,and we are unaware of any chytrid-relateddie-offs in other areas of their range orany studies that have assessed Bd prevalencein this species. The stability of theBocas del Toro populations suggests thateither O. pumilio is able to physiologicallyor behaviorally cope with the disease or else Bd is not presentin this region. To distinguish between these alternative hypotheses,we tested for the presence of Bd in O. pumilio acrossBastimentos Island in the Bocas del Toro archipelago, Panama.Methods.—We captured adults from the leaf-litter at 17 transectpoints across Bastimentos Island (Fig. 1) during July 2007. Samplinglocations were chosen to ensure all areas of the island (approximatelyevery 2 km) were assessed for the presence of Bd.The dorsum, venter, and feet of five adults from each locationwere swabbed with a sterile cotton swab for a total of 85 individuals.Swabs were stored in dry microcentrifuge tubes and upon returningto the lab were refrigerated at 4°C until extraction. Individualswere released at the site of capture.Extraction of Bd DNA was accomplished using the methodologyof Hyatt et al. (2007). Taqman diagnostic quantitative PCR(Boyle et al. 2004) was used to detect presence of Bd DNA. QuantitativeTaqman PCR assays were performed in triplicate using anApplied Biosystems Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System followingthe protocol of Boyle et al. (2004). VIC TMExogenous InternalPositive Control reagents were used for the detection ofPCR inhibitors (Applied Biosystems following Hyatt et al. 2007).A sample was only considered positive for Bd if all three replicatesindicated a presence of the fungus. Prevalence rates werecalculated by dividing the number of infected individuals by thetotal number of sampled individuals, and 95% confidence intervalswere calculated based on a binomial distribution (StataIntercooled v. 10.0).Results and Discussion.—None of the 85 individuals sampledtested positive for the presence of Bd in any of the three replicates(95% confidence interval = 0–4.2%). Inhibitors did not appear tobe present in any of the samples. Our results suggest that there isFig. 1. Sampling locations for Batrochochytrium dendrobatidis in Oophaga pumilio frogs acrossBastimentos Island, Panama.either a very low level of Bd prevalence or that Bd is absent fromthe Island of Bastimentos. We have two hypotheses as to why Bdwas not detected in our study. First, Bd may not yet have reachedBastimentos Island. The geographic isolation of Bastimentos O.pumilio populations from mainland populations may have impededthe spread of the disease. The island is, however, heavily traveledby tourists, implying that populations on these islands may be moreconnected to mainland populations than expected by geographyalone.Alternatively, the apparent absence of Bd on Bastimentos couldbe due to unsuitable environmental conditions. Bd is limited bytemperatures outside the range of 4–25°C under laboratory conditions(Piotrowski et al. 2004), and the distribution and severity ofinfections appear to be correlated with rainfall and temperaturepatterns in wild populations (Kriger et al. 2007). However, Bd hasbeen detected in at least one population of Panamanian frogs thatTABLE 1. Climate data for Bastimentos Island, Panama (Hijmans et al.2005).Climate VariableAnnual Mean TemperatureMaximum Temperature of the Warmest Month (April)Minimum Temperature of the Coldest Month (February)Annual Temperature RangeAnnual PrecipitationPrecipitation of the Wettest Month (July)Precipitation of the Driest Month (March)Value25.8°C30.0°C21.0°C9.0°C3109 mm398 mm146 mm<strong>Herpetological</strong> <strong>Review</strong> 39(2), 2008 201

- Page 1 and 2:

HerpetologicalReviewVolume 39, Numb

- Page 3 and 4:

About Our Cover: Zonosaurus maramai

- Page 5 and 6:

Prey-specific Predatory Behavior in

- Page 7 and 8:

acid water treatment than in the co

- Page 10 and 11:

TABLE 1. Time-line history of croco

- Page 12 and 13:

The Reptile House at the Bronx Zoo

- Page 14 and 15:

FIG. 6. A 3.9 m (12' 11 1 / 2") Ame

- Page 16 and 17:

One of the earliest studies of croc

- Page 18 and 19:

TABLE 2. Dimensions and water depth

- Page 20 and 21:

we call it, is in flux.Forty years

- Page 22 and 23:

Feb. 20-25. abstract.------. 1979.

- Page 24 and 25: yond current practices (Clarke 1972

- Page 26 and 27: poles (Pond 1 > 10,000, Pond 2 4,87

- Page 28 and 29: ------, R. MATHEWS, AND R. KINGSING

- Page 30 and 31: Herpetological Review, 2008, 39(2),

- Page 32 and 33: TABLE 2. Summary of running (includ

- Page 34 and 35: FIG. 2. Responses of adult Regal Ho

- Page 36 and 37: PIANKA, E. R., AND W. S. PARKER. 19

- Page 38 and 39: BUSTAMANTE, M. R. 2005. La cecilia

- Page 40 and 41: Fig. 3. Mean clutch size (number of

- Page 42 and 43: facilitated work in Thailand. I tha

- Page 44 and 45: preocular are not fused. The specim

- Page 46 and 47: FIG. 2A) Side view photo of Aechmea

- Page 48 and 49: 364.DUELLMAN, W. E. 1978. The biolo

- Page 50 and 51: incision, and placed one drop of Ba

- Page 52 and 53: 13 cm deep (e.g., Spea hammondii; M

- Page 54 and 55: FIG. 1. Medicine dropper (60 ml) wi

- Page 56 and 57: esearchers and Hellbenders, especia

- Page 58 and 59: FIG. 3. Relative success of traps p

- Page 60 and 61: data on Hellbender population struc

- Page 62 and 63: aits sometimes resulted in differen

- Page 64 and 65: trapping system seems to be a relat

- Page 66 and 67: AMPHIBIAN CHYTRIDIOMYCOSISGEOGRAPHI

- Page 68 and 69: TABLE 1. Prevalence of B. dendrobat

- Page 70 and 71: Conservation Status of United State

- Page 72 and 73: TABLE 1. Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica)

- Page 76 and 77: is, on average, exposed to slightly

- Page 78 and 79: (10%) were dead but not obviously m

- Page 80 and 81: Submitted by CHRIS T. McALLISTER, D

- Page 82 and 83: FIG. 1. Oscillogram, spectrogram, a

- Page 84 and 85: FIG. 1. Adult Physalaemus cuvieri r

- Page 86 and 87: Répteis, Instituto Nacional de Pes

- Page 88 and 89: discovered 145 live hatchlings and

- Page 90 and 91: GRAPTEMYS GIBBONSI (Pascagoula Map

- Page 92 and 93: College, and the Joseph Moore Museu

- Page 94 and 95: FIG. 1. Common Ground Lizard (Ameiv

- Page 96 and 97: havior unavailable elsewhere. Here

- Page 98 and 99: 15% of predator mass, is typical fo

- Page 100 and 101: side the third burrow and began a f

- Page 102 and 103: We thank Arlington James and the st

- Page 104 and 105: mm) S. viridicornis in its mouth in

- Page 106 and 107: NECTURUS MACULOSUS (Common Mudpuppy

- Page 108 and 109: LITHOBATES CATESBEIANUS (American B

- Page 110 and 111: Research and Collections Center, 13

- Page 112 and 113: BRONCHOCELA VIETNAMENSIS (Vietnam L

- Page 114 and 115: Oficina Regional Guaymas, Guaymas,

- Page 116 and 117: MICRURUS TENER (Texas Coralsnake).

- Page 118 and 119: declining in this recently discover

- Page 120 and 121: 80.7372°W). 02 November 2005. Stev

- Page 122 and 123: this effort, 7% of the 10 × 10 km

- Page 124 and 125:

the knowledge of the group. The aut

- Page 126 and 127:

which is listed under “Rhodin, A.

- Page 128 and 129:

noting that Sphenomorphus bignelli

- Page 130 and 131:

256 Herpetological Review 39(2), 20

- Page 132:

ISSN 0018-084XThe Official News-Jou